March 23rd, 2023, 12:36

(This post was last modified: March 23rd, 2023, 13:06 by Chevalier Mal Fet.)

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Historian's Corner: October - December, 1808: Napoleon in Spain

By the end of October, the Spanish patriots could muster something approximating an army of 120,000 along the Ebro, facing 75,000 French soldiers on the far side. I say it was only approximately an army - there was no supreme command, the various provincial generals and the juntas they 'served' preferring to squabble over rank and precedence, the men were largely untrained, brave enough but unsteady and unreliable in combat, and there was no overall strategy or plan beyond standing around and waiting for Napoleon to attack. The Spanish compounded their error by scattering up and down the river - The Army of Galicia on the left composed 30,000 men. In the center, about 34,000 in the Army of the Center (appropriate enough), and on the right, 25,000 in the Army of Aragon, scattered from Saragossa to Barcelona. Burgos held a sort-of reserve of 13,000 men, and Barcelona played host to 20,000 Spaniards besieging an isolated French corps. Behind this scattered nonsense, there were about 80,000 more second-line Spanish, militia and raw recruits to the colors mostly, in something like 5 or 6 different detachments. Call it 200,000 Spanish total against Napoleon, not counting various guerrillas and partisans in the Pyrenees. Finally, slogging its way from Lisbon to hte Ebro line were 20,000 British regulars under Sir John Moore. Moore had spent hte last half-decade reforming and retraining the British army - although Europe didn't know it yet, the British army under Moore was the finest, best-trained, best-disciplined force in the world. Moore could count on 13,000 more reinforcements joining him under Baird's division via Corunna, in the northwest. Spanish intransigence and incompetence in supporting this expeditionary force meant that Napoleon wouldn't have to worry about it until mid-December.

Against this, Napoleon fielded close to 200,000 men in a variety of corps (the exact composition varied a lot over the campaign, so I can't give precise corps identities). His plan was simple enough - a central thrust over the Ebro, followed by two simultaneous outward wheels to trap the two Spanish wings in Navarre and Catalonia and destroy them, while the central army was free to sweep down on Madrid. The counteroffensive began on November 7, 1808, as the French swept forward all along the front against the Army of Galicia, routing the disorganized Spanish armies utterly. By 9 November, 67,000 Frenchmen were pounding down the road to Burgos, while Napoleon amused himself re-arranging and reorganizing the Army of Spain. The 10,000 Spanish defenders were swept away by the 10th. The Spanish Army of Galicia was saved from complete destruction only because it ran like hell away quicker than the French could pursue. On the other flank, the offensive against Aragon and Catalonia got underway two weeks after that against the western armies, and by November 23 Castanos' 45,000-strong army was destroyed by 30,000 Frenchmen at the Battle of Tudela. In both cases, though, Napoleon was frustrated that his armies had not moved more quickly and cut off the retreating Spaniards. Further, thousands of partisans were beginning to swarm behind the lines and harass the supply convoys. Still, the front was shattered and the road to Madrid ripped wide open. Apart from Moore's little (but tough) army struggling through the plains towards Salamanca, not one organized force remained to oppose France.

The action at Somosierra, 1808

Accordingly, on November 28, the second phase of hte offensive began and the French raced to Madrid via Somosierra Pass. There was a short but sharp battle there against Spanish remnants attempting to block the pass (celebrated by the charge of the Polish Light Horse against a Spanish battery), and by December 5 Madrid had changed hands for a third time back into French hands. All that remained was to smash the English army and dispatch occupation forces back to Portugal and the south of Spain.

However, there was one last surprise for Napoleon. Confident that Moore was beating feet for Lisbon, the Emperor ignored him and left 17,000 men under Marshal Soult (who had taken over Bessiere's corps after that marshal was too slow for Napoleon's tastes in the frontier battles) alone in northern Castile. Moore had indeed been planning on beating feet, but then word reached him that Madrid was heroically resisting Napoleon's advance, and that fresh Spanish armies were regrouping in Leon, to the north. There might be a chance, Moore thought, that he could swing north and threaten Boney's communications with France, which might lure him away from Madrid. "If the bubble bursts and Madrid falls," he wrote to his division general Baird, "we shall have to run for it."

The bubble had already burst, though Moore did not know it. He moved north against Soult's II Corps in Leon, reasoning that if he could catch the marshal as he went after Spanish partisans, he could surprise and scatter the French. Napoleon would HAVE to respond to that. On December 21, he found Soult still snug in his camps, not on the march as Moore had hoped, but the cavalry clashes that ensued alerted Soult and Napoleon to the danger. With blood in his eye, full of wrath, the Corsican ogre came boiling up from Madrid with his legions, and Moore had to run like hell to survive. So run like he did, and the French ran after him.

The race to Corunna, 1808-1809

Over the rough mountains of northern Spain Moore and his plucky 20,000, Britain's only field army, sped. Close on their heels came Napoleon himself, with 80,000 of the finest infantry in Europe. Bitter cold, rain, and snow beat down on the weary troopers of both armies, but the men shoved aside their discomfort and trudged on. English stragglers who fell behind, through exhaustion, sickness, wounds, or drink (as happened in some towns they passed through) instantly fell into French hands. Napoleon himself rode at the forefront - he was the first man into the village of Valderas, entering it scarcely two hours after Moore's rearguard had evacuated. Irritated, Marshal Ney pointedly commented, "Sire! I thank Your Majesty for acting as my advance guard!" By heroic efforts, though, Moore kept just ahead of Napoleon over the mountains and through the winding valleys down to the port of Corunna, on the northwest coast of Spain. Frustrated and refusing to be associated with failure, Napoleon handed over command of hte pursuit to his marshals and departed for France - there were rumblings of renewed war with Austria after Bailen and he needed to be ready to receive the Habsburgs again. Napoleon left the Peninsula, never to return.

Moore staggered with an army that was more stragglers than soldiers into Corunna on January 11th, but there was no Royal Navy to receive him. Soult, after Napoleon's departure, took a few days to rest and reorganize his own weary legions before drawing up in pursuit - but even as he arrived on the 14th, welcome sails of Royal Navy warships appeared over the horizon and bore into Corunna harbor to evacuate the British army. The sick and wounded went first, and by the 15th only 15,000 soldiers remained to face Soult's 20,000 encircling forces. Soult launched a heavy attack in a desperate attempt to prevent the escape of Moore's survivors, and Sir John coordinated a brilliant defense at the Battle of Corunna through the afternoon and evening. Moore himself fell, struck down by a cannonball at the height of the fighting, but his gallant army carried on and drove the French into retreat. As night fell, the final British soldiers slipped aboard their transports and escaped.

Death of Sir John Moore at Corunna, January 17, 1809

The Spanish campaign superficially resembled Napoleon's earlier triumphs in Italy, Germany, and Poland. He had conquered a vast nation, destroying or driving into the sea every army his enemies brought against him. An ally was on the throne, Portugal and Spain were in the Continental System, and the French Empire was at its greatest extent. But under the surface, problems brewed. The partisan war had never abated, and in fact, grew worse. French detachments, couriers, and convoys were eternally under siege in Spain's rugged mountains, and Napoleon's subordinates had disastrously mismanaged the campaigns before his intervention. It had taken 3 out of every 5 of all French soldiers to re-subdue the country after the disasters at Bailen and Vimiero. And it never went away. The Spanish ulcer, as Napoleon came to refer to it, remained for the rest of his reign, festering, absorbing blood and treasure, and never nearer completion than it had been in May of 1808. Napoleon never did cut his losses and withdraw to the Ebro or even over the Pyrenees, but kept throwing good money after bad. In the end, it was one of the first signs of his coming downfall.

But for now, Napoleon was again triumphant, and in 1809 one final success awaited him - as Austria, encouraged by the results of the Spanish, once more took the field. Another showdown on the Danube loomed.

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

AGEOD Spring 1809: January - May 1

Lots of activity in the Italian theater as our first offensive onto French (satellite) territory kicks off, while the main front is snowbound for most of this run.

After a long, wintry siege, as snow sets in Marshal Hohenzollern, in command of I Korps (senior to Warnecke, sadly, who has better stats) belately bestirs himself, apparently no longer content with tent life as it gets chilly. I Korps' 90,000 men hurl themselves at a shivering French garrison, clinging to the Austrian capital with their fingernails and now hundreds of miles from the front lines:

With that, there ARE no more real organized French forces left in my territory, and I think the year of raids has finally come to an end.

There is one bit of exciting news in January. Behold, a secret project I worked on since the fall of 1808: The grand Habsburg navy:

It boasts:

1st Battleship Squadron - 3 first rate ships of the line. SMS Uskoke, 80 guns, SMS Laudon, 74 guns, SMS Python, 74 guns.

2nd Battleship Squadron - 3 third rate ships of the line. SMS Futak, 64, SMS Lacy, 52, SMS Trabant, 52

1st Corvette Squadron - 3 brigs for scouting and courier duties. Venus, 18, Guerrerra, 18, Bellona, 18

1st Galley Squadron - 6 galleys captured from the Ottomans for coastal work.

1st Transport Squadron -3 transports escorted by the frigate Komet, 36

2nd Transport Squadron - 3 transports escorted by the frigate Guerriera, 36

3rd Transport Squadron - 3 transports escorted by the frigate Bellona, 36

4th Transport Squadron - 3 transports escorted by the frigate Medea, 36

All told, we now field 6 battleships, 3 frigates, 3 brigs, 6 galleys, and 12 transports for a total of 31 warships. It would be destroyed by the Royal Navy in about two hours, by the French Navy in about the same, BUT it's not going to fight the French navy. This force, which is capable of transporting about 25,000 men in one go, is intended for the sole purpose of capturing the Russian base at Corfu when the time comes. It's good enough to drop the French naval power ratio to only 5x my own instead of 999x! My little fleet of 256 power thus is opposed by about 1250 French power in warships.

In Rumelia, fighting with the Ottoman brigands rages all through the spring, with the massive armies of cavalry melting away, only to re-emerge and hit us again a few weeks later:

With Russia's arrival in force, though, this area is fully secure and I am able to march on Tirana once again. Maybe this time I'll finish Albania off for good?

The Spring Campaign In Italy

My Italian spring campaign is opportunistic. Gouvion St. Cyr's corps, which compelled me to evacuate Italy entirely last summer, is encamped for the winter at Bologna alongside multiple formations from the Kingdom of Italy:

My intention for the campaign is to swing south, as Joseph's III Korps already has, cut him off from French positions at Genoa and Milan, and drive him into the Adriatic to be destroyed. So, Joseph moves south into the Apennines, while Mack moves the main army onto the plan of Ferrara, and cavalry patrols move to cut off the north of the Po and escape to the south. Then Mack will launch an attack on Bologna.

By February 1, the operation is smoothly under way, although a few French division-sized forces are hovering:

February 5-7 sees the Battle of Bologna, with 35,000 casualties one of the biggest since the Battle of Mantua 3 months before. This time the ratio is in our favor:

The French forces under St. Cyr are destroyed, and all that remains is an Italian force trying to move to the south:

By February 15, as Pino's force moves south to Rimini pursued by Joseph, Mack accepts the surrender of Bologna's entire garrison:

Only two weeks into the offensive and already France's position in northeast Italy is a shambles.

I order Mack to push on to Rimini, the last real holdout on the eastern half of the peninsula, while Joseph crosses into Tuscany and head for Florence:

And by March 1, the operation continues as Pino's entire force is trapped in Rimini and Firenze is placed under siege:

See the situation by March 8, as Florence surrenders and the tide of White is reaching for the Tyrrhenian sea itself:

Finally, on March 8 Mack storms Rimini, pursuing the last holdouts of hte Italian army, and the result is a massacre:

By March 15, all of Italy south of the Po as far as Genoa is in Austrian hands, and we are ready to begin our direct attack on Milan itself, having destroyed its covering armies. The entire artillery park of the Kingdom of Italy, for example, is more or less in my hands:

Overall, a very satisfying spring campaign in Italy. Will cover the operations along the Rhine, where the action is heating up i nMarch and April, next time.

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Winter 1809 - Alsace Front

Yes, I think from this point on, we can redesignate the Danube Front to the Alsatian front. Charles has spent the winter camped in the foothills of the Alps at Memmingen. By the end of January, John's II Korps has reached him fresh from the liberation of Bohemia, and has set up as the advanced guard:

Winter camps in the Black Forest, 1809

The front is quiet for most of winter, which is a harsh one - snow lasts until late April in many places. But morale is high in the Austrian camps. After more than three years of long, harsh warfare, we've reached a watershed: We are now in striking distance of the Rhine, and French national territory itself. So, while Mack's Royal Army wins victories in northern Italy and begins to bring about the final collapse of that Napoleonic puppet, Charles and John's men shiver in their tents and dream of the battles to come in spring.

The campaign gets an unexpected start early. II Korps receives orders from Charles to take advantage of a break in the weather in late February and move up to Basel, officially in Switzerland, as a jumping-off point for the invasion of France to come. Basel is on the left bank of the Rhine, which will save us a river crossing later, will secure our southern flank against thrusts from the direction of Marseilles, and is a good supply base for the push into Alsace.

John in position at Basel, lower right center. Across the center - the road to Paris, at left!

A few weeks later, though, as John re-establishes himself in the winter quarters, who should appear in Mulhouse but Boney himself, leading a corps-sized formation of the Grande Armee?

Couriers fly down the roads to Charles' camp at Memmingen, and the Archduke instantly puts his men on the roads. He will march due east, violating the neutral territory of Baden (which would otherwise make an excellent jumping-off point), and join up with John before Napoleon attacks, if he intends to. If not, then I will go after him myself.

by the end of March, 2800 French power is facing off with 3700 Austrian power, both armies divided in half by the Rhine:

Charles isn't due to reinforce John until March 27, but I feel that whoever can concentrate on the same bank of the river first has an advantage. Napoleon knows it, too, and does something unexpected: Instead of attacking John before Charles can reinforce, he instead attempts to cross the Rhine and attack Charles before John can react. Davout is left with a corps to contain John at Mulhouse. If this had been the Austrian army of 1805, clumsy and slow, he probably would ahve succeeded. But we have grown immensely in 4 years, and the army moves fast and efficient. Charles already has bridges over the Rhine to Basel when word reaches him of the French advance, and the canny general is able to slip away before the Grande Armee arrives. Napoleon finds his birds flown, and Charles is linked up with John:

We don't miss our own opportunity for a counterstroke, and Charles leads an attack on Davout to sever Napoleon's communications back over the great river:

The Battle of Mulhouse, 2 April 1809, would be little noticed - 115,000 Austrians in the two corps against Davout's 17,000 defenders - except for one thing. It's the first time French soil has been violated by a foreign enemy since the historic Cannonade at Valmy, 17 years ago. Davout is beaten and Mulhouse is stormed.

The Army of Italy (soon to be renamed the Army of the Rhine* because I'm sick of that goofy name) rests in Mulhouse for two weeks, before Charles crosses back into Baden in an effort to trap and destroy Napoleon. There is minor skirmishing between the two armies around 20 April, but Napoleon is already flying away to the east, escaping Charles:

With Napoleon pulling east towards the Danube, Charles abandons the pursuit, instead intending to draw Napoleon after him. The Emperor may not also be aware of I Korps fast approaching the front, either. Hohenzollern's formation has reached Memmingen, and he is ordered to pursue and attack Napoleon, while Charles moves on the great fortress-city of Strasbourg to secure a firm base on the Rhine. II Korps covers the southern flank at Mulhouse - Besancon.

By April 27, Strasbourg has been stormed...

and Besancon is under siege, while I Korps is closely locked with Napoleon. The situation in Alsace by May 1:

The re-formed Army of the Rhine, Charles's army, is ensconced at Strasbourg (center), an excellent depot and fortress securing our line of communications back to Austria. I Korps is in the Black Forest at Ludvigshafen, attempting to contact and deal with Napoleon, somewhere in the same province (right center). In the lower center, II Korps is besieging Besancon fortress to secure our left flank. Paris is at left.

Here are the plans for the summer campaign. Objective: Paris.

We will move in our present 3 corps formations. John will lead II Korps in the south, securing the left flank of the advance by taking Besancon and Dijon, holding those two places against threats from the south. Charles and the Army of the Rhine will move to Nancy and Metz to secure the initial lodgment in Alsace and extend our hold to Lorraine, defending there until I Korps can reach Strasbourg. I Korps is the main reserve of the army at this time.

In Phase 2, I Korps will move north, if practicable, and defend the northern shoulder by taking first Landau and then the Mainz - Trier line, which will shield us against intervention from French forces in the kingdoms of Holland and Westphalia.

The flanks thus secured, Charles should be free to push straight down the road Verdun -> Rheims -> Paris. We shall then dictate peace to the Corsican Ogre from the Tuileries.

*Anything corps level and below can be renamed at will in AGEOD's engine, via alt-clicking on the unit's tab and typing in what you like. However, armies tend to get autogenerated names, like Kaiserlichte Armee or Armee du Dalmatia, Home Army, etc. To rename them, you have to disband the army (which nominally costs national morale and victory points), type in your new name, and then reform the army on the same turn (saving you the NM and VP loss). It should then keep the same name. All your corps are disbanded when their parent army is, so you have to go through and manually reform all of those, as well. It's a bit clunky, so I kept the goofy Army of Italy name even though Charles evacuated Italy in the summer of 1805, never to return.

*

Posts: 2,102

Threads: 12

Joined: Oct 2015

That strikes me as a horribly unbalanced navy (three fat wallowing first rates for that many total ships?), but I have no idea what the game actually requires.

It may have looked easy, but that is because it was done correctly - Brian Moore

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

(March 24th, 2023, 16:02)shallow_thought Wrote: That strikes me as a horribly unbalanced navy (three fat wallowing first rates for that many total ships?), but I have no idea what the game actually requires.

Well, the game only lets you recruit in squadrons, not individual ships. If I'd had my druthers, I'd have one first-rate flagship backed by two squadrons (5-7) third rates for my main battle line, and then about as many frigates and brigs for scouting.

I DO have another frigate squadron completing, which will tkae the total number of frigates to 6. Brigs don't seem worth building, since I only need this fleet to take Corfu, not blockade France or anything.

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Historian's Corner - Crisis on the Danube: the 4 Day's Campaign (January - April, 1809)

The surrender at Bailen, followed by Napoleon's withdrawal of veteran troops from Germany to deal with the crisis, awakened the war party in the Austrian court. The Habsburgs had been nursing their wounds since 1805, and had been carefully rebuilding and reforming their army after the disasters of Ulm and Austerlitz. Led by the emperor's brother Archduke Charles, their best field commander, the army had been rebuilt to a strength of 340,000 soldiers in 11 corps backed by 200,000 Landwehr militia. The new corps, shamelessly copied from the French system, were vastly more flexible in operation and better-organized than the old divisional system. The Austrians also instituted reforms in tactics, copying French skirmishers, column assaults, cavalry and artillery organization. Charles was unenthusiastic about risking war in 1809, wanting more time to complete his reforms and fill out his ranks. But the war party prevailed. They argued that Napoleon might never again be as vulnerable as he would be in the spring of 1809, with so much of the Grande Armee absent in Spain and far from Germany. To delay was fatal - the losses of territory and tax revenue would ultimately doom the monarchy. An aggressive gauntlet thrown down could provoke a nationalist uprising in Germany to match that of Spain - the Confederation of the Rhine, the kingdom of Bavaria, and the kingdom of Westphalia could match the Spanish dominions of Galicia, Catalonia, Castile, Andalucia, and others in tying down Napoleon's resources. Finally, Prussia and Russia might be induced by French weakness to rejoin the war. Between that, British intervention, and the Spanish ulcer, Austria had every chance to regain her lost provinces. So, by February, 1809, the Hasburg monarchy resolved on a surprise attack on France.

Strategic situation in Europe, 1809.

For his part, Napoleon counted on his alliance with the Tsar, and his German satellites backed by the remaining French corps under Davout and Bernadotte, to keep the Austrians in line. So it was a nasty surprise to him that the Tsar concluded to sit back and let things play out, and he was forced to improvise an army to meet the New Model Austrians. The core of the new force, dubbed the Army of the Rhine (the Grande Armee had been broken up when Ney, Victor, and Marmont had been hustled to Spain back in October) was Davout's old reliable III Corps and a few odds and sods scattered in garrisons across Germany as far as the Oder. Davout had perhaps 80,000 men to face more than seven times that many Austrians.

When the Emperor arrived back from Spain early in January, he immediately set about strengthening Davout by any means necessary. The German satellites were called on to furnish 100,000 men. A new IVth corps (Soult's old formation had been disbanded, he led II Corps in Spain) was raised and given to Marshal Andre Massena. More conscripts were raised (confusingly, including another II Corps, this one under Oudinot). By hook and by crook, Napoleon managed to assemble 174,000 men in his new "Grand Army of Germany" by March 30th. There were about 80,000 more in Italy and Dalmatia, a second front, 18,000 Poles from the Duchy of Warsaw, and 16,000 Saxons led by Marshal Bernadotte. It was an army of 275,000 in total, then, to pit against 320,000 frontline Austrians - but it was an army of conscripts, auxiliaries, raw and untested boys and old men. In terms of quality it was far below the Grande Armee of the 1805-1807 glory days. Napoleon tried to compensate by shoveling in hundreds of cannon, but he only managed about 311 guns. Pound for pound, the reformed Austrian army would be about as good as the new Grand Army of Germany - Napoleon's leadership would have to make up the difference.

At first, though, Napoleon was not in command. Busy raising and equipping the fresh levies, he temporarily placed Marshal Berthier - his chief of staff since his first command in Italy - in charge. Napoleon issued a flurry of instructions - too complex to go into detail here, although they are admittedly fascinating - that quite overwhelmed Berthier, hopelessly out of his depth in independent command. When the Austrian offensive began unexpectedly soon and in an unanticipated direction, Napoleon's instructions flew out the window and Berthier was at sea.

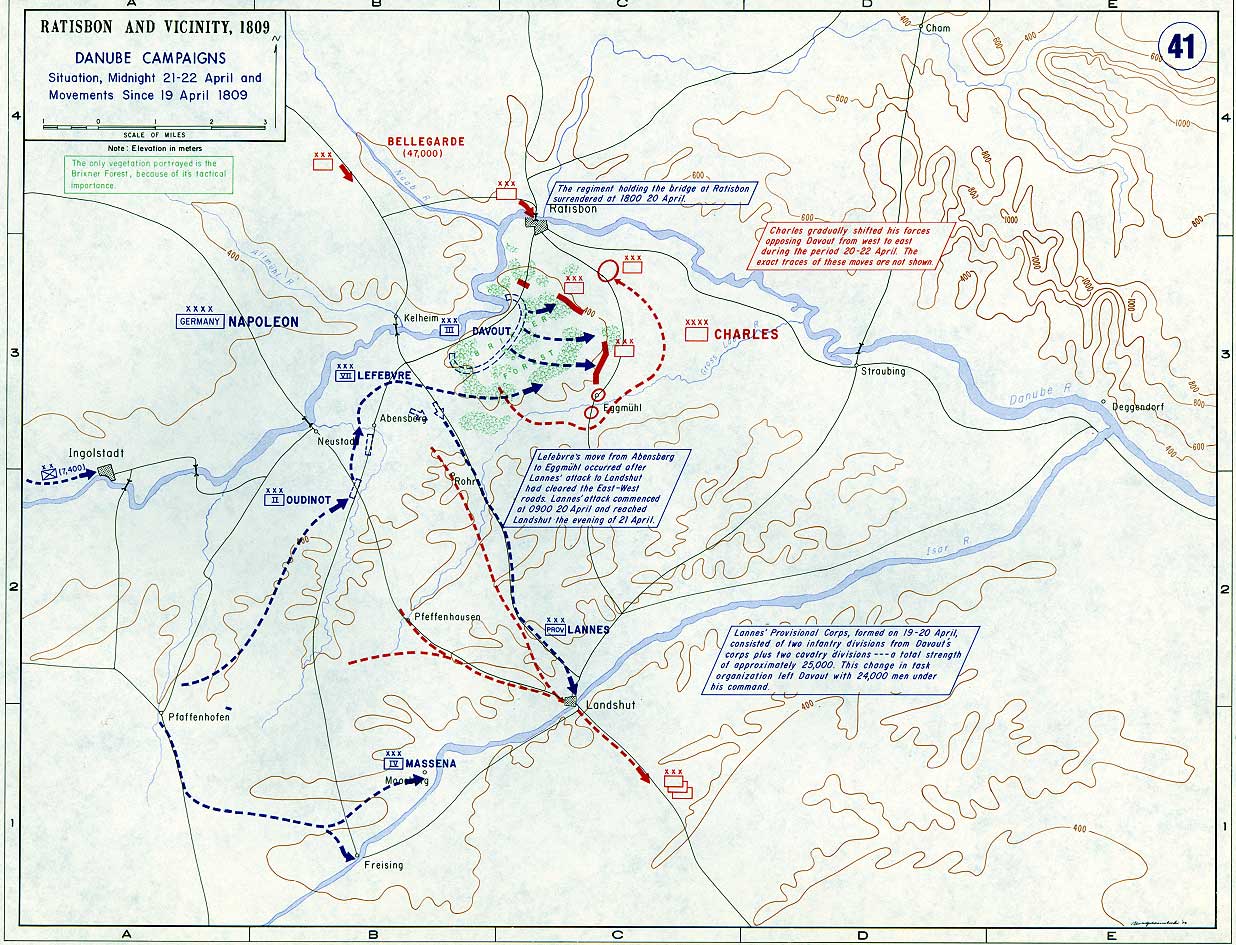

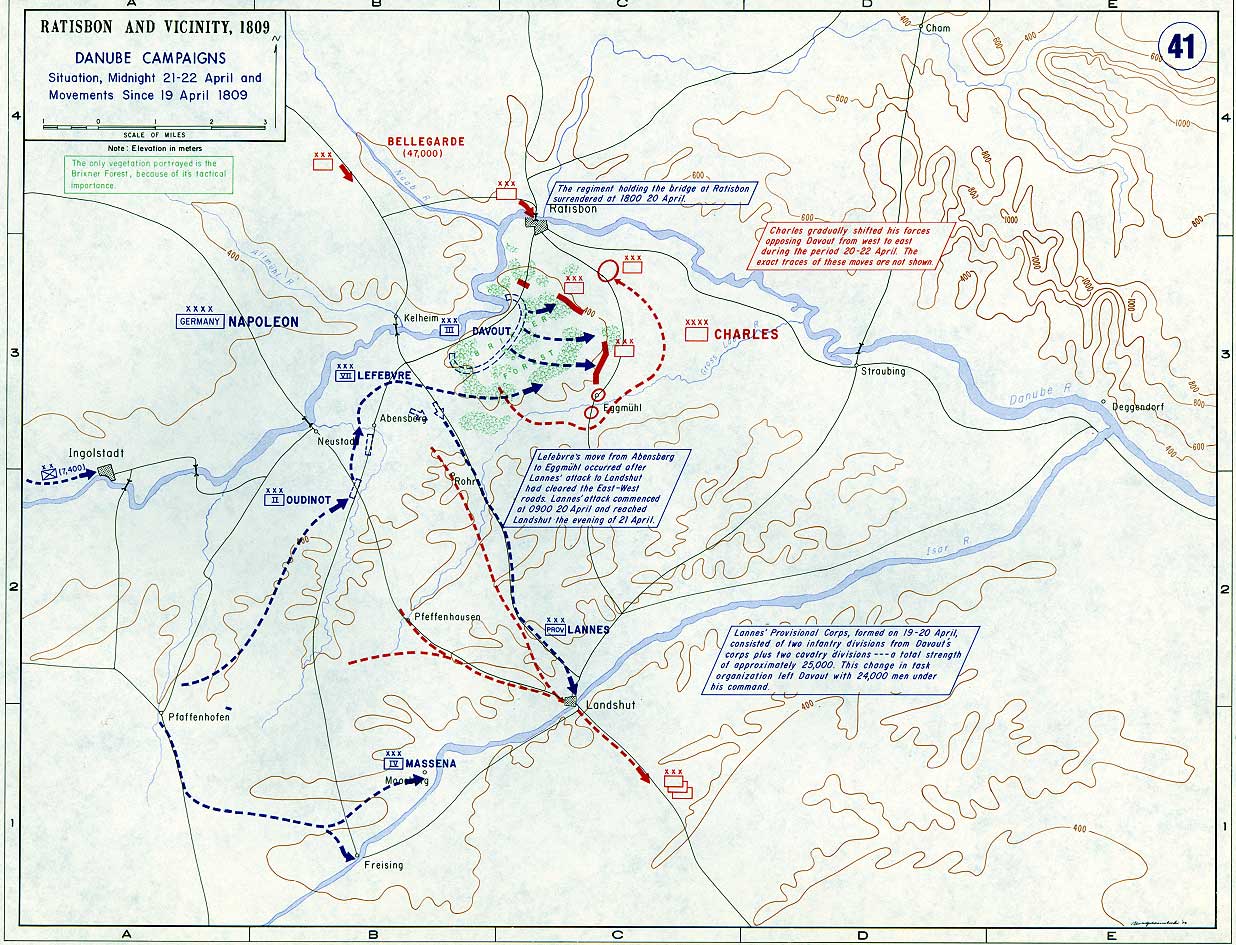

The Austrian attack began, without bothering with a formal declaration of war, with Charles' main army invading Bavaria on April 9, a full week before the French thought they'd be ready. The Archduke fielded 6 of his shiny new corps south of the Danube, 2 more in support north of the river. Only the 3 Bavarian divisions of Lefebvre's corps opposed him at first, but luckily for the French the Austrians had not lost their habitual slowness, and they were nearly a full week even coming in sight of the forward French positions. Berthier quite lost his head, however, and instead of following Napoleon's instructions of concentrating near Donauworth on the River Lech, in the event of an early Austrian attack (in strict fairness the pace of events had left Napoleon in Paris behind, and a confusing blizzard of messages, arriving out of sequence or sometimes not at all, descended on Berthier), the Chief of Staff tried to concentrate at Ratisbon (Regensberg) on the Danube, extremely forward and very near the Austrian advance. If the Austrians took the town before the French could assemble their full army there, they would control the only viable bridges in the area, with III Corps isolated on the north bank and the rest of Berthier's army on the south. Davout had been marching to Ingolstadt from his positions north of the river, where he'd easily be able to join Berthier, but now the marshal's instructions were to march forward again.

The result was that by April 15, the Grand Army of Germany was in two massively separated wings: Davout with near half the army marching on Ratisbon, Oudinot and the reserves with another near half more than 75 miles to the south near Augsburg, and only Lefebvre's Bavarians linking the two. One hard push by Charles through that screen and he would be between the two wings of the French, with Davout cut off by the river, and the Austrians able to pick either to fall on with all their forces. Napoleon, speeding from Paris as soon as word reached him of the war on April 13th, arrived not a moment too soon on the 17th. That same day the Austrians met Lefebvre's Bavarians at Landeshut, on the Isar river, and threw them aside. There was now nothing between them and Ratisbon, where Davout was now gathered.

Situation, 17-19 April. Davout attempts to squeeze southwest up the Danube while Charles tries to trap and destroy him.

Now it was a race. Napoleon needed to race to III Corps' aid with Oudinot and Massena, while Charles needed to reach Ratisbon and destroy III Corps before the French army could link up. Davout must try to link up with Napoleon before he could be picked off in detail. The French misread the Austrian deployments, overestimating the force north of the river and underestimating that south, and so Napoleon placed Davout in even more danger by having him cross south of the Danube at Ratisbon - placing him right in Charles' path. The Emperor only realized the error on the 18th.

To the end of his life, Napoleon was proud of the subsequent campaign, known variously as the Four Day's Battles or the Eckmuhl campaign. In less than a week, he totally reversed the situation, drove Charles into retreat, and even assured himself of the capture of Vienna. Although a few mistakes robbed him of total victory, he still, despite the poor quality of his troops, and the compromised, handicapped position he opened the campaign in, gave the Austrians a severe drubbing.

First, Napoleon instantly grasped that the only way to save Davout, trapped (thanks to Berthier and Napoleon's errors) with his back to the Danube and 80,000 Austrians bearing down on him, was to mount such a threat to Charles' flank that the Archduke would be forced to divert reinforcements to deal with him. Massena was ordered to take IV Corps and move on Landeshut, which would sever Charles' line of retreat over the Iser and force an Austrian response. Davout scuttled south and west from Ratisbon, and Charles, overconfident, thinking he had the quarry cornered, was slow in his attack - only the westernmost Austrian columns brushed against III Corps' rearguard at Tengen. Early on the 20th, Oudinot's II Corps was put in motion in the center to link directly up with Davout. By dawn, Napoleon received word that Charles, repulsed by Davout at Tengen and sensible of Napoleon's rapidly mounting threat on his left flank, was in full retreat.

Now Napoleon thought he had the quarry in the bag, and a flurry of orders raced out from Imperial headquarters. Massena was urged to speed his march to Landeshut and cut Charles' escape path. Marshal Lannes, newly arrived from Spain but without troops, was given some of Davout's formations and formed a provisional corps to attack and break Charles' center. Oudinot was to continue his march and link up the divided French wings, joining Lefebvre's VII Corps with Lannes' attack, and III Corps woudl remain on the defensive, holding Charles in place. His center pierced and left turned, Charles would be driven back against the Danube and destroyed.

The Eckmuhl campaign, 20-22 April, 1809. Napoleon thinks he is enveloping the Austrian army between the Danube and Iser - but Charles is already making his escape.

By 11 am on the 20th, VII Corps and Lannes had already crashed through the Austrian V Korps, under Archduke Louis in the center. The right hook, Oudinot's II Corps, had sharply bloodied Hiller's corps on the Austrian southern flank. It seemed Napoleon was already cutting the Austrians to pieces and by dawn on the 21st he was boasting that he had achieved "another Jena." Davout would now move back to Ratisbon, keeping the Austrian I and II Korps from interfering from the north of the river, and finishing off III Korps on the south. Lannes and Lefebvre, having crashed through Louis, would make for Landeshut to join Massena and seal off Charles' other escape path. The Austrian army would be destroyed and the road to Vienna would lie open.

Napoleon had made a few errors, though. First, Davout and Lefebvre hadn't beaten all of Charles' army on the 19th, but only a few leading parts of it. Only Louis and Hiller had been harmed in the campaign so far. Davout was facing three complete Austrian corps between him and Ratisbon. Second, he assumed the bridge at Ratisbon was either in French hands or destroyed by the garrison - in fact, the regiments Davout had left had already surrendered and the Austrians had full communications over the Danube. Finally, he assumed Massena's IV Corps had already reached Landeshut around Charles' flank and had stopped that escape route - but Massena, faced with spring floods and terrible roads, had pushed his men hard to only make it barely halfway to that bridge. Thus, Hiller, with about three Austrian corps of the left wing, was already escaping over the Iser. Although Hiller lost about 10,000 men and 30 guns in the battle of Landeshut that day, and a battalion of grenadiers stormed the bridge under fire and held a beachhead on the far side in Landeshut itself against all Austrian attempts to dislodge them, the Austrian army was not destroyed and fled to safety beyond the Iser. Frustrated, Napoleon detached a small pursuit force and swept down the Iser with the rest of his flanking force to take Charles' main body in the flank and destroy it.

On the 22nd, Davout was facing most of Charles' army with only about 25,000 men for the culminating battle of the campaign, at Eckmuhl. Charles was moving to drive in Davout's left flank, near the Danube river bank, and secure his line of retreat to Ratisbon (Napoleon had only just become aware that the Austrians had the town and the bridge, intact). Charles also hoped to drive Davout off the river and in turn sever Napoleon's lines of communication with the Danube - so that each opponent was attempting to turn his enemy's left, and the two armies were moving in a great counter-clockwise wheel through Bavaria. The Iron Marshal held through the morning, however, and late that afternoon Napoleon appeared on Charles' flank with the rest of the French army. Davout ordered an attack all along the line, which was carried out with great gallantry. Charles decided the game was up and ordered a withdrawal through Ratisbon as evening fell on the 22nd. The exhausted soldiers of the Grand Army of Germany, having been marching and then fighting with furious energy for five days, dropped into exhausted sleep practically on the battle field.

On the 23rd, the last of the four days, Napoleon urged his army onto the heels of Charles, and all remaining forced converged once more on Ratisbon and its vital bridge. The old medieval walls were bravely defended by 6,000 men of the Austrian rearguard, and all day, assault after assault was hurled back. Charles had escaped, but Napoleon could march on Vienna without Ratisbon - it posed a vital threat to his rear otherwise. A formal siege would bog down the entire campaign and invite Prussia or Russia to pile in, or the national rising in Germany that Austria was banking on. There was no choice but a frontal storming of the city. Lannes was ordered to take Ratisbon and the bridge at all costs.

Storming of Ratisbon, April 23, 1809

After two costly assaults had failed, no more troops would step forward and volunteer - it was certain death to brave those walls. Baron Marbot, Lannes’ aide, recorded the scene that ensued:

Quote:Then the intrepid Lannes exclaimed, ‘Oh, well! I am going to prove to you that before I was a marshal I was a grenadier - and so I am still!’ He seized a ladder, picked it up, and started to carry it toward the breach. His aides-de-camp tried to stop him, but he shouldered us off.

I then addressed him as follows: ‘Monsieur le Marechal, you wouldn’t want to see us dishonored - but so we shall be if you receive the slightest scratch carrying a ladder towards the ramparts, at least before all your aides have been killed!’ Then, despite his efforts, I snatched away one end of the ladder and put it on my shoulder, while Viry took the other and our fellow aides took hold of more ladders, two by two.

At the sight of a Marshal of the Empire disputing with his aides-de-camp as to whole should mount first to the assault, a cry of enthusiasm rose from the whole division. A rush of officers and men followed - the wine was drawn, it had to be drunk.

Marbot was the first man over the wall, and Ratisbon fell that evening, April 23.

In the week since his arrival on the 17th, Napoleon had completely reversed the situation. Charles had received such a drubbing over the 4 day’s fighting from the 19th - 23rd that he wrote his brother, the Emperor, that another such battle would see Austria with no army left. The Habsburgs had suffered 30,000 casualties, the army was split into two parts separated by the Danube, both wings retreating, and the road to Vienna was open. While a decisive victory had eluded him by the narrowest of margins, Napoleon had severely shaken the Austrians and ensured that no one else would join the war of the Fifth Coalition. Before May was over Vienna would have once more fallen into French hands.

However, that same month would also see Napoleon suffer his first ever clear defeat on the battlefield, at the grim fighting at Aspern-Essling, fast approaching.

March 27th, 2023, 13:17

(This post was last modified: March 28th, 2023, 06:53 by Chevalier Mal Fet.)

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

AGEOD May 1809 - The campaign in Alsace

My pace is going to dramatically slow here, basically down to month by month updates because the 1809 campaign is so complex - both in reality and in our AGEOD universe. In reality, the 1809 Danube campaign (my personal favorite of Napoleon's) is both very intricate and filled with bloody battles, so I can't breeze over it like I could, say, Junot in Portugal. In our AGEOD universe, I'm campaigning in France itself for the first time, with Napoleon himself present, so taking time is important.

Situation, May 1, 1809:

In reality, at this point Charles' army was retreating into Bohemia and Napoleon was barreling towards Vienna (again). Here, though, we have driven the French out of every foot of Austrian soil (woo!) and began our counter-invasion of France about a month ago.

Charles is at Strasbourg, our major base for the push on Paris. To his north and west are the fortresses of Alsace - Nancy, Metz, and Verdun. Clearing those will open the road to Rheims and Paris. Holding the left or southern flank is John's II Armeekorps, a weaker formation besieging Besancon. Hohenzollern's I Armeekorps is in reserve at Ludvigshafen, attempting to corner Napoleon, who is leading a small corps-sized formation around the Rhine. I don't want to push too far from Strasbourg until I Korps is there to secure the area, but I do feel safe enough pushing to the Nancy-Metz-Verdun area in Lorraine.

In the first week of May, Charles pushes from Strasbourg to Nancy and storms the place, while John storms Besancon. However, his 20,000 men are very badly worn out by the siege and attack:

John musters 2 divisions and 2 more brigades with assorted batteries - about a 3-division force. I'll be able to fit 5 divisions with supports into this corps once I can form more! But for now he's the weak link of the Army of the Rhine, and Napoleon is at Freiburg crossing towards Basel. Hohenzollern is ordered to continue his pursuit.

Napoleon surprises me by swinging right past Basel, Mulhouse, and on to Besancon, where luckily I had ordered John to take shelter in the fortress while the men recover their morale and cohesion. Hohenzollern's lumbering I Korps is a full six days behind by now, not due to arrive until May 22. I don't think John can hold out that long against a determined attack, so II Korps is in grave danger - but if I Korps catches Napoleon after the assault we could drub him in return.

In Lorraine, on May 19 Charles easily conquers Verdun fortress, surely a presage of German fortunes to come in this French city:

The road to Paris is open to us, but with Napoleon and Soult on the loose in Alsace with 2 corps I can't march on the French capital yet. Charles needs to deal with the Corsican upstart and secure his base, first, so I order him to return to Alsace.

May 21 finds the following situation. I Korps is at Besancon, where Napoleon did NOT attack, but moved on before Hohenzollern could catch up. Charles is at Verdun, while the heights of the Meuse opposite are occupied by Soult's beefed up division. I also have a division defending Nancy. Napoleon split his corps, taking one division north towards Nancy while the rest marched west.

I order Charles and Hohenzollern to rendezvous at Nancy. I hope to catch Napoleon between them, or for him to get hung up in battle at Nancy and for the rest of the army to catch up.

Soult's force, mostly engineers and artillery with very limited infantry, is brushed aside with heavy loss:

Hohenzollern catches up to Napoleon's rearguard at Epinal, but the Emperor is able to slip away to the west and evade the trap:

Situation in Alsace-Lorraine as of 1 June after those maneuvers:

The Army of the Rhine and I Korps are adjacent blocking Napoleon's road north to the occupied Lorraine cities. Instead the Emperor is defending the road to Dijon. II Korps is mostly recovered at Besancon and ready to move on that city, too. Our plan here will continue - I Korps keeps Napoleon occupied and secures the base (hopefully an offensive down the Rhine as far as Mainz at some point), while Charles I think is clear to move on our next goal of Rheims. Paris by July?

March 27th, 2023, 17:32

(This post was last modified: March 28th, 2023, 07:06 by Cyneheard.)

Posts: 5,636

Threads: 30

Joined: Apr 2009

Says a lot about Napoleon that you can have 2 armies with 2-2.5x time his power around him, and he's not in trouble...yet.

Posts: 6,471

Threads: 63

Joined: Sep 2006

What happened at Verdun? Zero Austian casualties but some French escaped and no guns were captured, so presumably the fortress didn't just surrender...? Did the artillery troops take the guns and run and then the rest surrendered without a shot fired?

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Sometimes oddities like that happen - the post-battle report shows ALL troops present in a province, not just those engaged in the battle itself, so most likely there was a battery of horse artillery or something that was passing through and didn't join in the garrison's surrender. Or maybe not! The thing is buggy and weird a lot of the time.

|