March 28th, 2023, 12:12

(This post was last modified: March 28th, 2023, 12:22 by Chevalier Mal Fet.)

Posts: 3,924

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Historian's Corner: The First Defeat (Aspern-Essling, May 1809)

Following the Four Days' Campaign/the battle of Eckmuhl, Napoleon had two options. He COULD attempt to cross the Danube at Ratisbon and pursue the defeated Charles into Bohemia's mountains, or he could move down the Danube and take Vienna with near-certainty. Since Charles had a 2-day head start, and there were other Austrian armies to worry about (ie, Archduke John, with 50,000 men in Italy), Napoleon thought the best chance of forcing peace was to capture Vienna and try to force a decisive battle. III Corps with its veterans was once more sent north of the Danube to harry Charles' retreat, but the rest of the army - Massena's IV Corps, Lannes' provisional corps, Oudinot's II Corps, and Lefebvre's Bavarian VII Corps - was sent down the river towards Vienna. Along the way, Napoleon was reinforced by the Imperial Guard (marching up from Spain) and by Bernadotte leading the armed forces of Saxony, dubbed IX Corps.

The Danube valley in May, 1809, as represented in Wars of Napoleon.

Blocking the way were the remnants of Charles' left wing, cut off in the fighting and driven over the Iser at Landeshut, about 3 corps under Hiller. The Austrian marshal gathered 40,000 men behind the Traun river and Massena, not knowing Lannes had already outflanked the position, pushed IV Corps into town in a very sharp fight. 3,000 Frenchmen, including 5 colonels, died unnecessarily storming the town with its bridge. Still, the brute force approach worked, and Napoleon's hurrying columns easily outmarched Charles, who was himself making haste behind the Bohemian mountains to reach Vienna first. By May 10, Vienna was in sight, and on May 13 under the threat of bombardment Vienna surrendered - after the garrison escaped over the Danube and burned its bridges. Hiller and Charles united there on the heights of Wagram on May 16, bringing the Austrian army back up to strength - 115,000 men - facing only 82,000 Frenchmen in II Corps, IV Corps, Guard, and the cavalry reserve. VIII Corps and IX Corps, 38,000 men, were at the Traun, watching an Austrian corps of 25,000 on the far side of the Danube and dealing with local partisans. Davout's 35,000 were also guarding the lines of communication after recrossing the Danube, and VII Corps with 22,000 was near Salzburg watching the outlying bits of Archduke John's force. Napoleon had badly dispersed his men in the rush to Vienna, another error, possibly thinking he had knocked all the fight out of Austria. It was far from the truth.

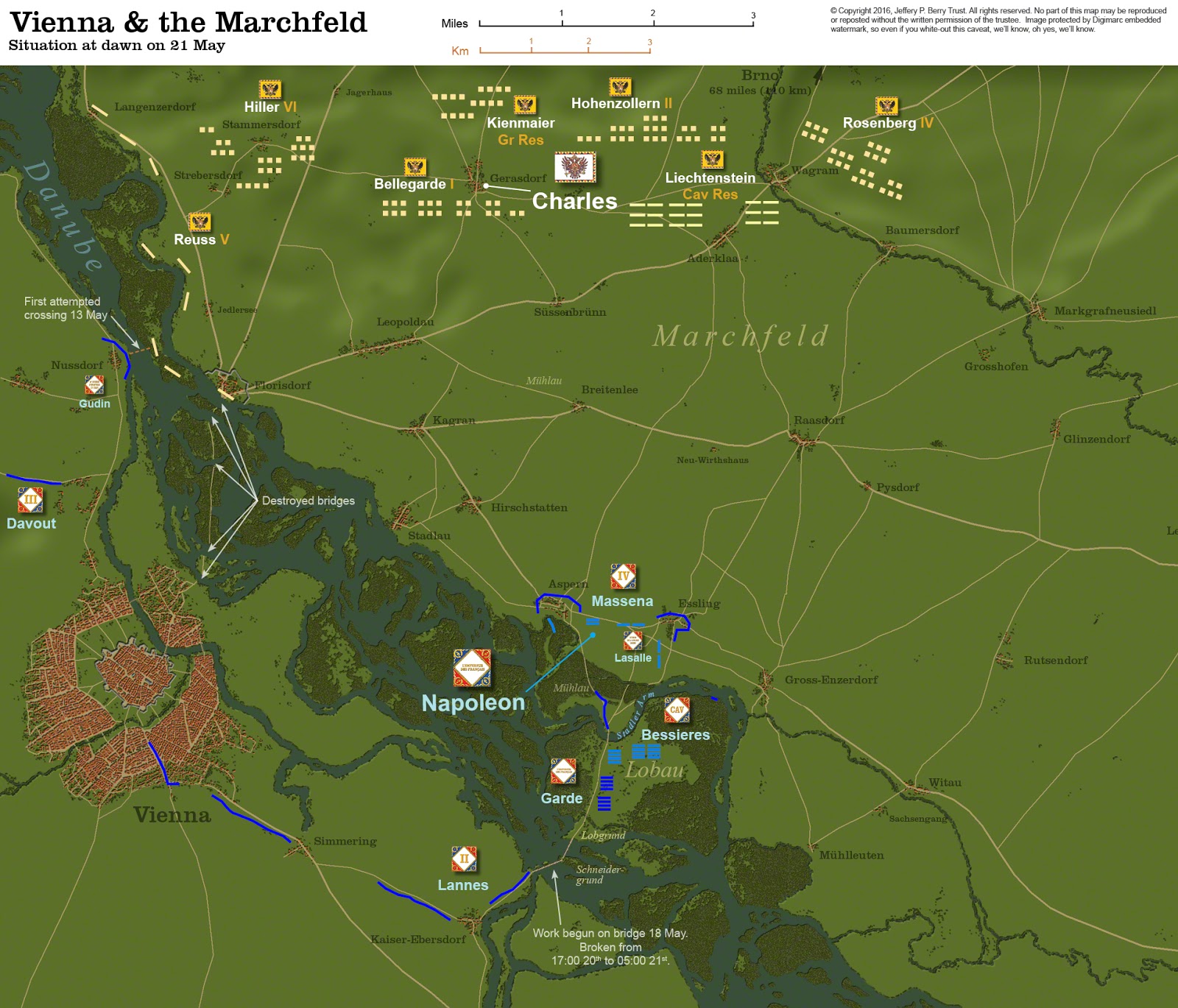

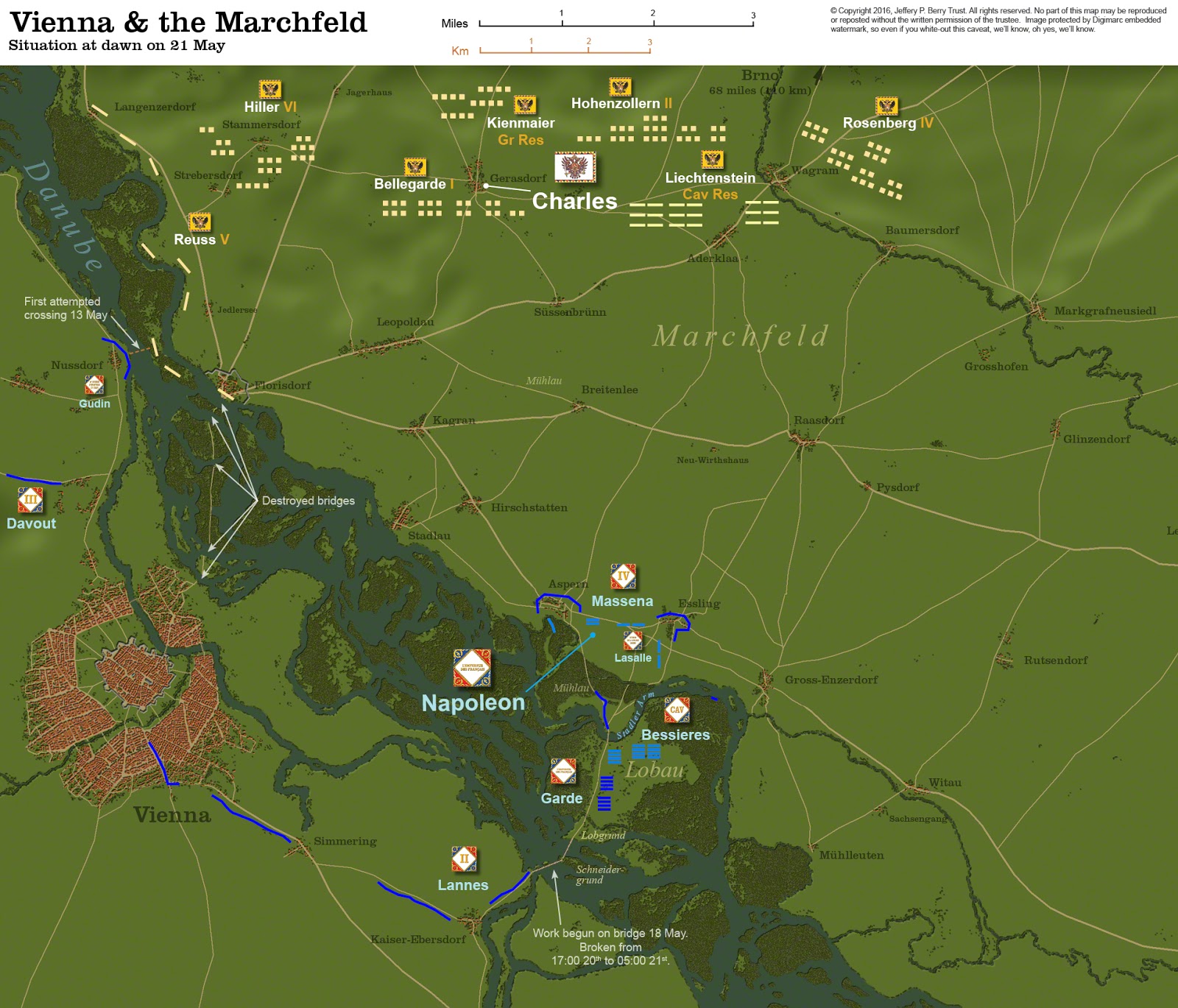

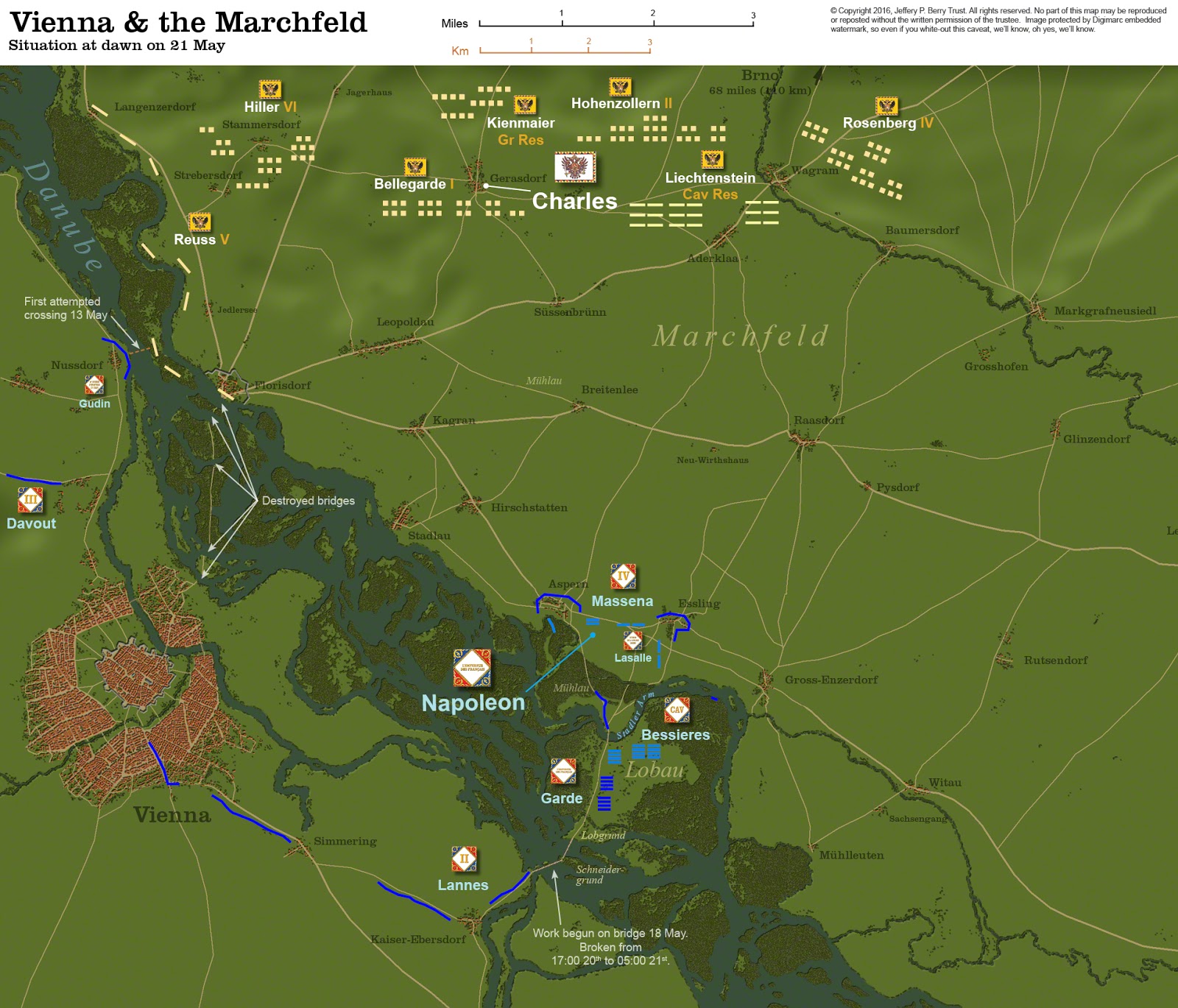

The only way to win the war was for Napoleon to cross the spring-swollen Danube and crush Charles' army before he could be joined by John with 50,000 reinforcements. But the bridges were destroyed and there was no other way across. To cross with the whole army would let Charles slip around Napoleon's left, recross the river, and cut his lines of communication somewhere near Linz. To wait would let John come up and reinforce his brother. So, Napoleon would have to cross with only part of the army - and the first step would be to capture a bridgehead. It was incredibly hazardous to attempt - the Austrian army was encamped just across the river, the Danube was prone to sudden spring floods, and the Austrians up the river could launch attacks on any temporary bridges - but caution was not in Napoleon's nature. Was he not the Emperor, victor of a hundred battles? The attempt would be made.

The crossing point selected was the island of Lobau, about 4 miles outside Vienna. The island would be a useful stepping stone in the crossing, serving as an artillery and supply base, while shielding the long bridges to the south bank. It was easy to reach by floating downstream from Vienna. However, Napoleon had made yet another error in the campaign - his intelligence of the far side of the river was poor, and it was believed that the Austrian army was gathering around Brunn, when in fact it was encamped in the hills just beyond the river. Charles was taking steps to fortify all the hills lining the floodplain, intending to trap Napoleon's army in the low ground when it came over the bridges. Charles made his own mistakes of course, leaving large detachments to the rear and along the river to the west.

The Vienna - Lobau - Wagram area. Vienna is at lower left. Just down river is the large island of Lobau, selected by Napoleon as the jumping-off point for his trans-Danube attack. Charles' army, mostly unknown to Napoleon, is encamped on the hills across the Marchfeld floodplain.

Lobau Island was occupied on the 19th, and late in the evening on the 20th lead elements of IV Corps crossed over to the northern side of the Danube, taking possession of the small village of Aspern and its neighbor Essling, two hamlets that would serve as strongpoints defending the bridgehead in case the Austrians tried to interfere. So far, the only interference had come from a large hulk, floated by the Austrians along the swift current and smashing the bridge from Lobau to the south bank, temporarily cutting the army off. It was an ominous forewarning of what was to come, but there was still no major battle expected. Large numbers of French light cavalry had crossed first, but Massena's horsemen had failed to detect Charles' army.

![[Image: Bridge%2Bover%2BDanube%2Bbreaking%2Bby%2BMyrbach.jpg]](https://2.bp.blogspot.com/--2i3_jH9qcI/V0CkkCNA41I/AAAAAAAACVg/Ok3MI9Kep3Y1OFllvDvvsnSOyWBAd2qYQCLcB/s400/Bridge%2Bover%2BDanube%2Bbreaking%2Bby%2BMyrbach.jpg)

The rickety bridge over the Danube breaks - not for the last time

Charles was massing for an attack on the bridgehead. Three corps - VI, I, and II Armeekorps - were to attack the western village of Aspern. IV Armeekorps would pin down Essling, and the army cavalry would link the two wings. All movements would begin at noon.

The quiet morning of May 21 deceived the French into thinking all was well. Division after division quietly filed across the narrow bridge and fanned out on the plain beyond, setting up a defensive perimeter around Aspern and Essling. No fortifications were constructed at either village. Napoleon's attention was all on the vital bridge from Lobau to the southern bank. The Danube had risen 3 feet overnight, and a growing stream of Austrian missiles - fireships, logs, other debris - was battering the span as the Austrians hurled everything they could find into the river upstream. Shortly after noon, even as the Austrian army was emerging from the hills onto the plain, the bridge broke again, once more interrupting the flow of reinforcements and supplies.

I Armeekorps storms Aspern, 21 May 1809

The leading elements of I Armeekorps took the French completely by surprise at about 1 pm, whirling out of a convenient dust storm and into the French outposts at Aspern. The Austrians poured into the village streets, and only through heroic efforts did General Molitor cling to the village. All afternoon the Austrians came at the village, each assault being met with a storm of fire, and each assault being turned back. By 5 pm, though, all three Armeekorps were arrayed around Aspern, and now Charles ordered a general assault. In the hours that followed, the village changed hands no less than six times, as Molitor brilliantly fought his division, then reinforced by Legrand's division, then St. Cyr.

In the center, the Austrian cavalry attack met General Bessieres, in command of hte cavalry reserve (Murat was away in Naples, the kingdom Napoleon had awarded his marshal), and the two sides fought all afternoon. And on the French right, the village of Essling was attacked by only one Armeekorps, and Lannes easily held his ground. As sunset fell over the smoky plain, the two armies fell into a stalemate. Charles began drawing up attacks for the next day, while Napoleon urgently wrote to Davout and attempted to summon all available soldiers to the embattled bridgehead. He had only 30,000 men over the river facing 100,000 Austrians. All reinforcements depended on the single fragile bridge to Lobau island, under constant bombardment and with a rising river. It was not out of hte question that IV Corps might be annihilated on the morrow. Knowing he would have to fight his way out of the trap he'd thrust his own army into (much like Bennigsen at Friedland, I might add), Napoleon successfully got most of Lannes' provisional corps across into the bridgehead overnight, and dawn on the 22nd found 60,000 French facing the 100,000 soldiers of Charles.

Fighting for Aspern, 22 May 1809

Even as the sky began to lighten, a fresh Austrian corps-sized assault swept into Aspern. Street fighting had never really died out in the contested village, and soon the battle was in full-swing again. Charles intended to continue his assault on the two keystone villages on either flank, weakening his own center in the process. Napoleon grimly hung on to both, and prepared to unleash Lannes and Bessieres against the center. At about 7 am, the drums beat the pas de charge, and Lannes' corps lunged into a maelstrom of Austrian shot and shell. The French artillery accompanying the attack was virtually wiped out by the fire, and the inexperienced French conscripts were formed into dense squares and columns of attack (I may do a post on small-unit tactics later), which suffered enormous but unavoidable losses. But Lannes advanced over the plain, and the Austrian center stretched, and stretched, and began to break - men streaming for the rear, guns and standards falling to Lannes' hands. Into this chaos plunged Charles, personally carrying a standard and rallying his men. The Austrian retreat subsided, the men reformed, and the situation stabilized.

Second day at Aspern-Essling, 22 May 1809

Now the momentum swung to the Austrians once more. The bridge broke again, stranding III Corps, just arrived on the battlefield from Vienna, on the south bank. Ammunition began to run low among the French defenders of the bridgehead, and Napoleon was forced to begin pulling back to the perimeter around Aspern and Essling. Charles went over to the attack all along the front by 10 am. The bridge was repaired, again. A burning, floating mill hurled from upstream smashed it, again. Napoleon realized that to continue the struggle might see the destruction of his entire army. He had to get his men back to the south side of the river, and regroup for another try at some other place, some other time.

Wounding of Lannes at the bridgehead, 22 May 1809

But first he had to get out of this mess he had gotten himself in. On the right flank, IV Armeekorps had at last overwhelmed Essling and seized very nearly the entire village. The reformed Austrian center was applying pressure now, too, and the entire French position was beginning to crumble. In desperation, Jean Rapp led 5 battalions of the Young Guard (a new division added to the old Imperial Guard) forward and drove the Austrians out of the village in a furious, bayonet-point struggle. Shortly after three o'clock, Napoleon was practically forced to return to Lobau by the Guard, and step by step the French began to contract their perimeter towards the bridges. The Austrians pressed them closely, the French repulsed them, the Austrians came on again, again they were driven back. Amidst the fighting, Marshal Lannes was struck by one of the tens of thousands of Austrian cannonballs that swept the plain that day. He was carried back over the bridges to Lobau. Lannes had been at Napoleon's side since 1796, that first halcyon campaign in Italy. He was one of the Emperor's only friends. When he died, 8 days later, Napoleon wept openly. Lannes was the first Marshal of the Empire to be killed in action.

Napoleon comforts Lannes in hospital, May 1809

Meanwhile, the battle at last drew to a close. The French perimeter held, barely, as the soldiers filtered back across the bridge to Lobau. Marshal Massena was the last man over, and then, shortly after dark, the bridge was drawn abck to Lobau. The French had lost about 22,000 men, or over a quarter of their army, in the two-day struggle, the Austrians had lost about the same.

Napoleon had suffered his first clear-cut check on the battlefield. Sure, he had at times failed to win - most notably at Eylau in the Polish campaign of 1807 - but he had never before been forced to relinquish the field. It wasn't as bad as it could have been, thanks to Charles' timidity, but losing 20,000 men and Marshal Lannes was bad enough.

In a word, Napoleon had gotten cocky. River-crossing doctrine was well-known and rehearsed in the early 19th century. Piles could be driven into the riverbed above the bridge, and patrol boats put in the water to watch for debris. The bridge could have and should have been secured against the Austrian aquatic bombardment. The French cavalry had failed utterly in its scouting duties, missing the entire Austrian army just a few miles from the crossing site. Napoleon had rushed the crossing, despite not knowing Charles' location, he had dispersed his troops widely and allowed himself to be outnumbered on the decisive field, he had contemptuously undertaken an extremely risky river crossing with insufficient scouting, preparation, or strength, he had led with the raw conscripts of Massena and Lannes instead of Davout's veterans in III Corps - all in all, not his finest day. He had grown complacent from years of beating the Austrians, not acknowledging the substantial improvement in their fighting qualities since 1805.

For now, Napoleon licked his wounds and gathered his strength. His next effort would be serious, and when it came, it woudl not be stopped. The result was the largest battle in European history up to that time: The sanguinary killing field of Wagram.

March 28th, 2023, 15:05

(This post was last modified: March 28th, 2023, 15:06 by Chevalier Mal Fet.)

Posts: 3,924

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

AGEOD Summer 1809 - June/July Campaign

Well boys, this is it. This summer we make our push for Paris, in an effort to win the war with France and bring about the downfall of Napoleon.

We'll start in Italy. On 1 June 1809, I kick off the Army of Italy's final offensive to liberate the north Italian plain, for the first time since the battle of Marengo 9 years ago.

Mack, despite outnumbering Milan's garrison 3:1, still manages to take 11,000 casualties defeating their 23,000-strong army.

Despite the effusion of blood, Milan's capital is stormed. To the south, the next day, Joseph fights a much tidier battle at Piacenza:

The Italian army here retreats into hte fortress, which is encircled rapidly. Joseph spends two weeks digging trenches and shelling a breach into the walls, and when the assault finally goes into the breach the demoralized garrison offers only token resistance before surrendering:

By July 1, the lightning campaign ahs seen Turin stormed by Mack's army, while Joseph is moving on Genoa, the last French holdout on the peninsula:

The siege of Genoa is short - I can't starve them out due to the port, so I order a rapid storming. The battle is, um, weird. I assume the garrison is stronger than the 200 shown here, or else the 5,000 casualties are REALLY embarrassing:

With that - 4 short, sharp battles costing about 25,000 Austrians all told over the two months - the French are totally cleaned out of Italy, and I am in position to start pushing my way over the Alps into southern France.

The March on Paris

Napoleon's rearguard again manages to evade Charles, his 30,000-strong corps tangling with the full 180,000-man army of the Rhine and getting away lightly:

Still, it's enough. I spend the month of June bringing Charles back up to Lorraine, to join up with his advance guard at Rheims. Napoleon is pursued by I Armeekorps down towards Lyon, but I conclude there is no strong danger to my flanks now. Further delay is pointless and it's time to move directly on the imperial capital:

Charles has marched all the way from Constantinople to Paris in about two and a half years (1 January 1807 - 1 July 1809). Now Charles will move to Rheims and join up with his advance corps, storming the city. I don't see strong garrisons, Rheims has only a weak curtain wall, and Charles is in excellent shape. We're going to move as rapidly as possible before Napoleon can shift around via Orleans to cover the city.

Situation in the south sees Napoleon and a few scattered formations being shoved away by the rest of the army of the Rhine:

It looks as if the Emperor is withdrawing west or south. He may need to cross the Loire and then attempt to reach Paris via Orleans - I Armeekorps is tasked iwth dealing with him. John's II Armeekorps is to seize Dijon as the anchor for the southern flank. Behind I have strung out weak garrison forces holding back equally weak French forces.

Overall state of Western Europe:

See the massive bulge from Switzerland into France as far as Rheims. In Italy you can see that we have overrun everything as far as Milan, with outposts at Torino while I try to bring up cavalry patrols to pacify the countryside.

The biggest battle in July erupts around Dijon, as Marshal Soult with 27,000 Frenchmen attack John's 22,000 men. Despite losing 1/3 of his army, more than Soult's losses, John is able to stubbornly hold his ground:

The French withdraw. The difference in national morale is showing here, as we would have lost this battle for certain back in 1805.

Here we are by the middle of July. Charles is at Rheims, a 4-day march from Paris. Napoleon has reached the Aube, closely pursued by I Korps:

THe time has come. Charles keeps his tiring but extremely buoyant troops on the road after only a few day's rest in Rheims. The sunny Gallic countryside is gorgeous in summer. Singing Habsburg troops file down the country roads, watched by wary French peasants. In the distance the spires of Paris are distantly visible.

July 12 - two days short of Bastille Day - sees Soult make another go at Dijon, attempting to draw troops away from the advance on Paris. But with more than 200,000 Austrians in France, there's only so much he can do, especially when I Korps reinforces II Korps:

Soult loses the last regiment of cavalry he has, and myriad other casualties, while John gets off lightly.

News of the victory at Dijon is overshadowed, though:

The same morning of July 12, in a short but furious battle, Charles overwhelms Andre Massena's small garrison at Paris, and 90,000 victorious Habsburg soldiers pour into the city. For the first time since the Hundred Year's War, the capital of France falls to a foreign enemy.

Madness ensues:

Napoleon is proclaimed overthrown and the French Empire dissolved after only 5 years of existence (the Emperor himself does not acknowledge this and fights on from his positions in the south of France), the Bourbons are declared restored. French national morale collapses as war-weary peasants just want to see the fighting come to an end:

Down to 32! France basically cannot fight anymore - they'll lose every battle. Note also that strength is down to 68% of our own.

Charles captures a MASSIVE supply dump and artillery park at Paris, the largest I've ever seen:

We, um, also declare war on Great Britain for some reason?

This fucking game sometimes, I swear.

Anyway, we have only a few objectives left to win a formal victory in the game (our victory points are VERY low because I have spent htem liberally on draft decisions and requisitions to fund the war effort - I NEVER have enough manpower!). Ulm and Frankfurt must be taken in Germany, and then we need to go after Prussia and Russia for our final objectives. From Prussia we need Breslau:

Breslau is at lower right center. Silesia is familiar to us from Rise of Prussia, when we captured this area from Austria. Now as Austria we need to take it back to be truly hegemons of Europe. Berlin is a short distance northwest, where King Frederick is visible with Russians transiting to the warfront in Westphalia (Prussians and Russians battling French there).

From Russia we need Kiev...

From Dubno in Galicia we can force-march to Zhitomyr and then to Kiev. Russia's armies are in the Balkans, Caucasus, and even Hanover, so a coup de main might succeed here.

...and we need Corfu:

A strength 300 garrison holds it.

In addition, I must retain Zurich, Turin, Milan, Florence, and Venice from our defeated French opponent, as well as Sarajevo, Bucharest, and Belgrade from the Ottomans.

Thus, we need to maintain our light occupation in the Balkans (amidst the hubbub you might spot that Ferdinand just overran Tirana at last, in the Corfu shot). We need to maintain at least one small army in France to keep the French down, since I can't make peace and gain the Italian cities necessary for victory. Frankfurt should be vulnerable separately from Breslau and Kiev, so we need one army for Prussia (Ulm and Breslau), and another for Russia (Kiev).

My plans are to go for total victory in 1810. We will divide our troops as follows.

II Korps will seize Frankfurt in the fall of 1809. The Army of the Rhine and I Korps will move to Bohemia - Moravia by winter of 1810. Then...

- The Army of the Rhine to march from Dubno to Kiev in summer 1810

- I ArmeeKorps to move from Koniggratz to Breslau in the spring of 1810

- II ArmeeKorps to move on Ulm in spring of 1810

- The Army of Italy to police France and maintain control of that state.

- III Armeekorps to patrol Italy and maintain control of that state.

- Ferdinand's Balkan occupation force, reformed as IV Armeekorps, to sail to Corfu and seize that island in summer 1810.

By my count, that will be every major objective taken by the end of next year.

I will probably continue the Historian's Corners through Waterloo, because I enjoy them, and then we'll jump to the last game I plan in this trilogy: To End All Wars, taking the Central Powers against the Entente!

Posts: 3,924

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Historian's Corner: The Last Success (the Battle of Wagram, June - July 1809)

It's interesting to me that the battles of Aspern-Essling and the greater, more hideous sequel, Wagram, are so little-known these days. Both battles were multi-day affairs that involved more total combatants than the Battle of Gettysburg, for example - and more total casualties, too. At the time it was fought, Wagram was the largest battle in world history, and in many ways I think Wagram (and the Danube campaign that preceded it) is the first example of modern warfare - multiple corps maneuvering over extended fronts, grinding battles of attrition, mass-conscript armies of hundreds of thousands following a common doctrine. Wagram more closely resembles the mass battles of World War II than it does even the linear gunpowder warfare of Frederick the Great.

In the days after Aspern-Essling, both armies drew back in a kind of daze, stunned at the violence that both had just passed through - Aspern-Essling dwarfed the carnage of earlier battles like Friedland or Austerlitz that had decided entire campaigns, and the two were still locked in a death-grapple on the Danube. Then Napoleon's resolve stiffened, and he set about making preparations for his next attempt at Charles.

All eyes on Vienna, summer 1809

Lobau Island was converted into a massive fortress, the great advanced bastion for his leap across the Danube. Palisades and fortifications were hurled up, the bridges to the south bank were finally strengthened and made permanent, good roads criss-crossed the growing camp, stockades pile-driven into the river above the vital bridges, patrol boats brought up and a flotilla created to control the river, hospitals, depots, and headquarters established. Captured Austrian cannon from Vienna's arsenals were integrated into the corps, bringing the total up to over 500 guns. Prince Eugene and General Macdonald came up from Italy with 23,000 men, driving Archduke John's army before them, followed by Marmont with 10,000 men in XI Corps from Graz. Bernadotte's Saxon IX Corps came, and Vandamme with a provisional corps. By 1 July Napoleon had concentrated 160,000 men in or near Vienna.

Across the river, Charles raised up 60,000 Landwehr to replenish his losses, waiting for John's arrival and a general German uprising (indeed, partisans in the Tyrol were already beginning to harass French communications) before going over the offensive. He was also distracted by the Polish front, where Archduke Ferdinand was sparring with the Duchy of Warsaw's Poniatowski and Russians ostensibly 'supporting' their French allies, and so missed the looming French preparations until 1 July. On that date, Napoleon opened a fire from his new base of Lobau on the Austrian fortifications at Aspern-Essling, swung a carefully-prepared and concealed floating bridge over the Danube, and sent over his first division. Messengers sped to Charles in his camp up on the heights of Wagram, and the Austrians made ready to receive the French on the May battlefields.

The Grande Armee crosses to Lobau, 4 July 1809

Meanwhile, though, Napoleon had secretly made preparations to cross the Danube, not from the north side of Lobau, but from the east. Days of secret preparations and night marches were suddenly unveiled when, before dawn on July 5, in a driving thunderstorm four pre-prepared bridges swung out from their hidden places on the south bank and locked into place on the far side of the Danube. French light cavalry, then II Corps, followed by III, IV, IX, the Guard, the Army of Italy, and finally XI Corps each in their turn, filing swiftly and efficiently over sturdy bridges, would out on the far bank and by midday the entire army, more or less, would be firmly ensconced on the same side of the river as Charles.

Charles wavered in indecision, unsure if the Aspern-Essling crossing was the French attack - there had been numerous scares and false alarms throughout June - or simply another deception operation. He didn't know if he should bring the army down onto the plains and fight the French at their bridgehead, as he had done in May, or if he should wait in his fortifications in the hills to receive Napoleon's attack. By July 3, he had settled on this latter course, and the army was pulled back around the village of Wagram, with a small stream, the Russbach, covering their front.

The pouring rain and booming thunder combined with a thunderous French cannonade from Lobau, and the first assault troops came over in small boats to storm the far shore ahead of Napoleon's masterfully designed swinging bridges. Oudinot and Massena fell upon the Austrian defenders on the plain, rapidly driving them back towards Charles' main position up on the heights, and it wasn't until 5 am on the 5th that Charles was notified that the main French attack had indeed begun.

French assault troops, 1809

Napoleon's plan was to wheel on the small village of Gross-Enzersdorf and hit Charles' left flank. This would drive a wedge between him and John's approaching army, still at Pressburg, a day's march away, and let Napoleon beat the two brothers in detail. All morning and afternoon, as the advance guard of II, III, and IV corps pressed Charles' forward defenders back towards Wagram, the rest of the army - Eugene's Army of Italy, Bernadotte's Saxons in IX corps, the Guard, Marmont's XI Corps, came into their assigned places in line. Massena drove the Austrians out of Essling, and then less than hour later Aspern fell, as he triumphantly recaptured the bloody battlefield of May. By 5 pm on 5 July, the opening of the main dance, the situation was thus. The Austrians line stretched in a great arc from a hill known as the Bissam, upstream of Vienna, all the way to the edge of the Wagram plateau, a distance of over 12 miles. On the right was V Armeekorps, led by Reuss, and Kollowrath's III Armeekorps. Klenau's VI Armeekorps was down in the plain near Aspern-Essling to delay the French. A reserve armeekorps and part of Lichtenstein's cavalry reserve completed this wing, about 65,000 strong, reaching about as far as the village of Aderklaa. Facing this was Massena's IV Corps, about 27,000 men. The Austrian left was composed of Bellgarde's I Armeekorps in the center, then Hohenzollern's II Armeekorps, the rest of the cavalry reserve, and Rosenburg's IV Armeekorps. These 90,000 faced Davout, Oudinot, Eugene, and Bernadotte, about 110,000 French. Napoleon had 35,000 more in reserve - the Guard (11,000), Bessieres cavalry (8,000), XI Corps (10,000), and Wrede's division, still crossing (7,000). Thus, Charles disposed of about 155,000 men in 8 corps, against 190,000 French in 7 corps. Napoleon held the inner arc and could more easily reinforce either wing, letting him concentrate all his forces against whichever bit of the Austrian army he chose. Charles was holding an extended front with only cavalry covering a full three-mile gap between Kollowrath and Bellegarde - he was desperately vulnerable.

Wagram, evening of 5 July 1809

Napoleon, accordingly, did not wait, but immediately launched his first attacks on Charles in the evening of 5 July. He did not want Charles to reinforce the center; nor did he wish the Archduke to escape overnight (as the Russians frequently had in Poland years before). Finally, he needed to beat him before John could bring up his own command to the battle. III Corps and II Corps would make a frontal attack on the Wagram heights, pinning down IV Armeekorps and II Armeekorps. Eugene and Bernadotte's fresh troops would then take Bellegarde and drive him out of Wagram, driving a wedge into the gap between him and Kollowrath 3 miles away.

The fighting on July 5 was a straight-ahead slugging match, then. Oudinot's men going over the Russbach and up the heights met a storm of canister and musket fire, and the Austrians held their positions until sunset, II Corps recoiling with a bloody nose. On their left, Eugene and Bernadotte strove forward against Bellegarde - just as the Austrians were wavering and beginning to break, though, Charles again appeared in person and rallied his battalions, bringing with him victorious reinforcements from the fight against Oudinot. The Italians wavered, and then broke, and ran - a panic never seen with the old Grande Armee at Austerlitz or Jena. The rout of the Italian troops took the wind out of the French sails - Bernadotte was driven back on the far left flank, Davout received his orders very late and made no progress on the right before nightfall. Bernadotte snidely remarked in camp that evening that Napoleon had badly handled the battle that day and "had he been in command, he would have forced Charles - by means of a 'telling maneuver' - to lay down his arms, almost without combat.' Bernadotte, never well-liked by the Emperor, was almost at the end of his tether.

Napoleon on the battlefield of Wagram, night of July 5 1809

Both sides lay their plans that night. For his part, Napoleon drew back Massena from his furthest advances on the left flank, and moved his reserves up a bit. Massena was to hold off any interference from the Austrian right, while Bernadotte and Oudinot repeated their frontal attacks. This would pin down the Austrians and enable Davout to roll up the Austrian left. Finally, when the Austrians were at the breaking point, Eugene would advance and shatter the Austrian center. Marmont and the Guard were in reserve. Charles pre-empted this plan. His only chance of victory was to envelop Napoleon's larger army and cut its retreat to the bridges at Lobau. The weak point was Massena on the French left. So, III and VI Armeekorps were to advance down the riverbank and take the bridges at Lobau. The center woudl launch pinning attacks around Aderklaa, the keystone of the French position - whoever held that village held the battlefield. IV Armeekorps would pin down Napoleon's right. Finally, John would appear behind Napoleon's right and seal the triumph. All attacks would begin at 4 am.

The pre-dawn Austrian attacks, preceded by the rumble of cannon, took the French by surprise, and initially Davout was driven back by the Austrians in his sector. By 6 am, though, the Iron Marshal had rallied his men and the French were recrossing the Russbach in triumph, driving IV Korps back. Hardly had Napoleon returned to headquarters after consulting with Davout through the crisis that another one erupted: Bernadotte's Saxons were disintegrating.

The Prince of Ponte Corvo, holding the vital village of Aderklaa, had evacuated it without orders during the night. Infuriated, Napoleon ordered Bernadotte to get his ass back in there and retake the village - now occupied by the Austrians - at all costs. Massena, too, was ordered to support his (idiotic) fellow marshal. The Saxons and IV Corps went in and turned the Austrians out of the village with the bayonet, but then up rode Charles (again) and personally led in grenadier reinforcements. The Saxons broke and fled out of the village, and Bernadotte, galloping at their head (apparently in an attempt to rally them) came one last time under Napoleon's baleful eye. "Is the type of 'telling maneuver' with which you will force Archduke Charles to lay down his arms?" he snapped. "I herewith remove you from command of the corps which have handled so consistently badly," he continued. "Leave my presence immediately and quit the Grande Armee within 24 hours." Bernadotte had been a non-factor in the triumphant Austerlitz campaign, he had bungled at Auerstadt, performed without distinction at Eylau and gotten himself wounded before the triumph at Friedland. While he hadn't failed, exactly, at Wagram, Napoleon was out of patience with I Corps' original commander.

Fighting in Aderklaa, 6 July 1809

Eventually, the situation at Aderklaa stabilized, but now a fresh Austrian attack developed on the left. The Austrian attack here, the decisive one aimed at severing Napoleon's escape path, was late in starting - it had taken hours for orders to reach the formations so far out on the right wing. But perhaps Providence was with Charles - for now the storm of two full Austrian corps, 35,000 men, fell upon the single division Massena had left to hold the left while he dealt with Aderklaa. Boudet, who had heroically held Essling for so long back in May, was tumbled towards the diversionary bridge on the north end of Lobau, and advance Austrian guards were already as far as Essling - ready to round the bend of the Danube and head for the fresh bridges on the east side of the island.

Charles' right hook, about midday at Wagram, 6 July 1809

Prince Eugene and his army of Italy stepped into the breach. The prince exercised his own initiative and brought his men and Macdonald's division into a new line, slowing the Austrian advance. With the time thus won, Napoleon boldly ordered Massena to shift back south with his three remaining divisions and establish a new line, marching south across the face of the Austrian army and throwing himself in the path of the attacking armeekorps. To do this, someone would have to plug the gap Massena's move would open in the French center, and Napoleon turned to Bessieres and his cavalry. Heroically, knowing it was a suicide mission, the horsemen threw themselves into the maelstrom in the center of the line, hurling charge after charge at the Austrians.

French cuirassiers salute the Emperor before going into action at Wagram, 6 July 1809

The Habsburg army parried these blows, but while warding off Bessieres, Massena was allowed to slip free and execute his march, saving the army. Finally, Napoleon assembled every single gun he could scrape together - nearly 100 - into a massed battery in the center, and as Bessieres' attack ran out of momentum and his survivors filtered back, the new grand battery opened up. A hail of roundshot and case shot held back Kollowrat, the massed batteries on Lobau island had opened up on the flank of the Austrians to the south, and Massena stabilized the situation. The crisis of Wagram had passed.

Davout injured but orders the attack to continue

Now it was time for events to play out to their conclusion. On Napoleon's right, III Corps ground forward, slowly, stubbornly, as slowly, stubbornly, the Austrian left gave ground. Davout had a horse killed underneath him, the advance went on; division general Gudin suffered four separate wounds, the advance went on. From his position at headquarters Napoleon saw the gunsmoke of Davout's advancing columns pass the vital point, and closed his spyglass with a snap. The moment had come. Imperial aides spurred over the plain in all directions, bearing their vital orders. Massena was ordered to attack. Oudinot was to attack. Macdonald, now holding the right center, would carry out hte decisive, shattering blow. All along the line, the Grand Army of Germany was going over to the offensive.

Napoleon sees Davout's smoke, Wagram, 6 July 1809

The sun gleamed off Macdonald's 8,000 bayonets as the drums once more beat pas de charge. The general formed his men into a massive, hollow square - multiple battalions in length and breadth - as he thrust into the center of a massive Austrian concentration, facing attack from all directions. His raw conscripts were too inexperienced to form anything more complicated, and the huge square (which became legend) was hugely vulnerable to the Austrian guns. Shot and shell tore at Macdonald's boys, but they rolled forward, and over the Austrian infantry who tried to block their path. Finally they crashed into the main Austrian line - and failed to break through. The white line wavered, the blue square wavered as well - and Napoleon had no reinforcements to give. Every French formation ahd been committed somewhere on the vast battlefield. At last, as the brave 8,000 were down to just 1,500 survivors, the Emperor managed to scrape up a few of Eugene's troops, the Young Guard, and Wrede's division, and flung them in. "You see the unfortunate position of Macdonald. March! Save the corps and attack the enemy; in fine, do as seems to you best." There were now only 2 regiments of the Imperial Guard left to face the whole of John's army, if the tardy archduke should at last appear.

Macdonald's square goes into the Austrian lines, Wagram, 6 July 1809

In the end, John did not appear. Davout still rolled back the Austrian wing steadily, inexorably. Massena had fought his way back as far as Aspern on the other flank. In the center, Oudinot at last overran Wagram itself. Charles decided the game was up and ordered a general withdrawal. The French, exhausted, were left in possession of the field. The great battle of Wagram drew to a close.

The final French advance at Wagram, 6 July 1809

It was not a triumph on the order of Austerlitz or Jena. There was no great pursuit - the French army was too badly used up for that. John's army at last made a fleeting appearance at 4 pm, before beating feet right back off the field when they saw that Charles was already retreating. 32,500 French lay dead or wounded on the field, a quarter of the Grande Armee. 7,000 more had been captured by the retreating Austrians. 40,000 Austrians were dead or wounded. Belatedly on the 7th, Napoleon lurched into pursuit of Charles, sending his men towards Znaim and Brunn, attempting to find which way his enemy was going. Marmont caught up to Charles at Znaim on 10 July, and by furiously attacking despite being outnumbered pinned him there until Massena came up. Charles had had his fill of war and sued for an armistice. The War of the Fifth Coalition, as it came to be known, was over.

For its audacity in challenging France again, Austria lost much of Tyrolia, all of Dalmatia, and all its Polish provinces, to Bavaria, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Duchy of Warsaw. The Russians annexed bits of Galicia, not to be relinquished until the fall of the Soviet Union nearly two centuries later. 3 million of Austria's 16 million subjects were lost. The Continental System was to be enforced. The Austrian army was not to exceed 150,000 men. Finally, Austria would ally with France.

The Danube campaign of 1809 is my favorite of Napoleon's (or perhaps second, after the 1813 German campaign). It is a modern war between two symmetrical armies, dispersed corps moving and combining and splitting - no longer is Napoleon running rings around an opponent stuck in the clunky 18th century mode of maneuver. Napoleon is at his best sometimes - the Four Day campaign, or the tactical skill and planning of Wagram, for example. But he's also at his worst - he trusted Berthier, when he should not. The arrogance before Aspern-Essling, the mistake in not pursuing Charles and instead taking Vienna, frequently dispersing his forces, mishandling his subordinates like Bernadotte. Wagram had been a bloody slugging match, nothing matching his finesse against these same Austrians 4 years before. Napoleon was indeed losing his touch. But he was still good enough to win. The Grande Armee was no longer the same. The old veterans were gone - in Spain, or part of Davout's dwindling III Corps. In their place were raw levies, brave enough, but unskilled. There were multiple panics at Wagram, for example. More and more soldiers were Bavarians, or Saxons, or Italians, not French. It was still, just, good enough to win.

It could be argued that Austria didn't gain all that much from its military reorganization in 1809. In 1805, she had been beaten in...2 months, from October to the beginning of December. The vaunted Charles reforms had led to her defeat in...3 months, from the beginning of April to the beginning of July in 1809. One extra month of resistance. But in actuality, Austria had badly shaken Napoleon. It had gone blow for blow and not been humiliated. Beaten, sure, overwhelmed in the end, but not humiliated. In the end, it was the last time that any nation would clearly lose a war to Napoleon and the French Empire.

In later years, when a French courtier made a snide remark about Austria's fighting qualities, a furious empire rounded on the man. "It is apparent," the Emperor said, "that you were not at Wagram."

Posts: 2,100

Threads: 12

Joined: Oct 2015

With tongue firmly in cheek, I feel it's a little harsh to call Bernadotte an idiot. He may not have been as energetic in seeking glory for Napoleon and France as some of the other marshalls, but if you were to view the Great Wars as a game of thrones, he ended up as the best placed French player ...

I like your suggestion that these campaigns had come to resemble WWI more than the "Cabinet Wars" of the 18th Century. It's arguably a set part of the road started by the French inovation of the "levee en mass" - the terrain of interest fills with enough men that maneuver becomes harder and harder, and long wars tend to remove any qualitative edge one side might have had to begin with, so it turns into a slogging match - at least until the next major technical and tactical innovation.

It's perhaps a good thing for Napoleon's reputation that he wasn't born any later ...

It may have looked easy, but that is because it was done correctly - Brian Moore

Posts: 3,924

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

(March 29th, 2023, 14:33)shallow_thought Wrote: With tongue firmly in cheek, I feel it's a little harsh to call Bernadotte an idiot. He may not have been as energetic in seeking glory for Napoleon and France as some of the other marshalls, but if you were to view the Great Wars as a game of thrones, he ended up as the best placed French player ...

I like your suggestion that these campaigns had come to resemble WWI more than the "Cabinet Wars" of the 18th Century. It's arguably a set part of the road started by the French inovation of the "levee en mass" - the terrain of interest fills with enough men that maneuver becomes harder and harder, and long wars tend to remove any qualitative edge one side might have had to begin with, so it turns into a slogging match - at least until the next major technical and tactical innovation.

It's perhaps a good thing for Napoleon's reputation that he wasn't born any later ...

To be fair to myself, I was mostly giving Napoleon's perspective at that time. Bernadotte was no fool, but he was a bit of an uninspired battlefield commander. He could be vain, lazy, slow to take the initiative, and had bad battlefield instincts, but for all that he was brave, a good administrator, and well-intentioned. He was kind towards captured enemies, courteous towards foreigners (like Swedes or his Saxons), and had a knack for adapting himself to circumstances, a survival trait in turbulent Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. And, of course, Napoleon's harsh treatment of him comes back to bite the Emperor in the ass in a few years, while Bernadotte's descendants are still crowned heads in Europe.

Posts: 3,135

Threads: 25

Joined: Feb 2018

(March 30th, 2023, 09:03)Chevalier Mal Fet Wrote: To be fair to myself, I was mostly giving Napoleon's perspective at that time. Bernadotte was no fool, but he was a bit of an uninspired battlefield commander. He could be vain, lazy, slow to take the initiative, and had bad battlefield instincts, but for all that he was brave, a good administrator, and well-intentioned. He was kind towards captured enemies, courteous towards foreigners (like Swedes or his Saxons), and had a knack for adapting himself to circumstances, a survival trait in turbulent Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. And, of course, Napoleon's harsh treatment of him comes back to bite the Emperor in the ass in a few years, while Bernadotte's descendants are still crowned heads in Europe.

When Bernadotte was mentioned, I was wondering what convinced the Swedes to make him their king. Did he look good in an ermine cape or something?

"I wonder what that even looks like, a robot body with six or seven CatClaw daggers sticking out of it and nothing else, and zooming around at crazy agility speed."

T-Hawk, on my Final Fantasy Legend 2 All Robot Challenge.

Posts: 3,924

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

(March 30th, 2023, 11:36)Herman Gigglethorpe Wrote: (March 30th, 2023, 09:03)Chevalier Mal Fet Wrote: To be fair to myself, I was mostly giving Napoleon's perspective at that time. Bernadotte was no fool, but he was a bit of an uninspired battlefield commander. He could be vain, lazy, slow to take the initiative, and had bad battlefield instincts, but for all that he was brave, a good administrator, and well-intentioned. He was kind towards captured enemies, courteous towards foreigners (like Swedes or his Saxons), and had a knack for adapting himself to circumstances, a survival trait in turbulent Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. And, of course, Napoleon's harsh treatment of him comes back to bite the Emperor in the ass in a few years, while Bernadotte's descendants are still crowned heads in Europe.

When Bernadotte was mentioned, I was wondering what convinced the Swedes to make him their king. Did he look good in an ermine cape or something?

Partially, yes. Mostly as part of the way Napoleon upended everything in Europe, from top to bottom.

So if you remember, after the Battle of Jena back in '06 the French overran all of Germany before Prussia could recover. Bernadotte, trying to make up for his blunders at the battle, was very zealous and diligent in the pursuit, and captured the city of Lubeck, along with a bunch of Swedish prisoners. The Marshal was extremely gracious to the captured Swedes and they travelled home full of tales of the generous and kind French marshal.

A few years later, after Friedland, Napoleon magnanimously gave Russia 'permission' to conquer Finland from Sweden as part of becoming buddy-buddy with Tsar Alexander. When Russia overran the province in 1809 - around the same time Napoleon, Bernadotte, and the Austrians were mauling each other up and down the Danube - the Swedes chucked their king out and found an elderly uncle to shove onto the throne. Unfortunately, said uncle was childless, so they needed a new heir. If that heir could be acceptable to the Emperor, all the better. His various brothers were all on thrones (Jerome, Louis, Joseph) or not interested (Lucien) at this time, so the next rank of the imperial nobility was the marshalate, including Bernadotte, already the Prince of Ponte Corvo. When everyone remembered what a stand-up guy he'd been after Jena, he seemed like the best possible choice.

Posts: 3,924

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

AGEOD Autumn 1809: August - December, 1809

With the fall of Paris, the War of the Third Coalition largely peters out, though skirmishing continues all around the French Empire. In Westphalia, Prussian armies overrun Jerome's kingdom and cross the Rhine at Mainz. The Austrian armies fan out from Paris as far as Rouen and Orleans, establishing a firm grip on the French heartland. Although Napoleon raids Charles's supply lines and raises franc-tireur partisans, there are no real major threats. Other parts of the armies establish control over the Rhone valley as far as Marseilles, while Genoa surrenders and Mack's Army of Italy links up with the Army of the Rhine. Soon only Toulon holds out on the French Mediterranean coast.

This fucking game. In order to meet my win conditions, I need the city of Frankfurt. So I have to declare war on Frankfurt's ruler, who is, of course, me:

That is, me in my position as Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, NOT my position as Francis II, Emperor of Austria. Of course, Francis has been dead for three years at this point, killed by a random Turkish cannonball in Bulgaria, but apparently hte mouldering corpse still rules both states. I also can't negotiate with myself, naturally, so the only way forward is to declare war on myself in order to seize the city from myself, for myself, so I can control all the cities I need for my victory conditions.

...I'm about this close to quitting Wars of Napoleon and moving on. I love AGEOD's ambition here, but this game design is just busted as hell.

Late in August, a raiding French column of regulars attempts a forlorn hope on the capital. The Army of the Rhine is already drawn up in defensive positions, and the attacking French columns are shot to pieces almost without loss to Charles:

That's the main caliber of battle right now - weak French divisions try to take key points, only to be bloodily repulsed by the garrisons. I slowly and steadily seize French cities, keeping my lines of communication open, and will gradually choke out the French empire. For example, my tentacles spreading over the Alps and down the Rhone towards Marseilles:

But by September, apart from Frankfurt (which will be seized more or less bloodlessly from the bastards ruling it, ie, me, soon), all my objectives other than the Russian and Prussian locations are officially controlled (meaning, I have found, at least 3 regular battalions of infantry in garrison, about 2400 men):

1809 ends without incident as I pull my major formations out of France, leaving Mack and Joseph on police duty while Charles' main army will move to Bohemia, for an invasion of Silesia and Prussia come spring.

The bad news is I can't declare war on Russia, nor can I degrade relations. My only diplomatic options are a state visit to enhance relations, or various begging/sending of expeditionary forces. It may be because Austria and Russia joined a coalition with Britain (scripted!) in June, 1805, and obviously Coalition members can't declare war on each other...except I, weirdly and unwillingly, declared war on Britain when I captured Paris, and Britain now refuses to make peace "because I am a threat to world peace." Jesus. This fucking game. Anyway, I can't leave the Coalition, since I'm at war with Britain, and I'm at war with France, and Britain and Russia are ALSO at war with France so we're clearly all in a coalition together...

If I can't figure this out by the end of 1810 and the Prussian campaign, I'm going to call this campaign there and move on.

Posts: 1,176

Threads: 12

Joined: Apr 2016

(March 30th, 2023, 11:36)Herman Gigglethorpe Wrote: (March 30th, 2023, 09:03)Chevalier Mal Fet Wrote: To be fair to myself, I was mostly giving Napoleon's perspective at that time. Bernadotte was no fool, but he was a bit of an uninspired battlefield commander. He could be vain, lazy, slow to take the initiative, and had bad battlefield instincts, but for all that he was brave, a good administrator, and well-intentioned. He was kind towards captured enemies, courteous towards foreigners (like Swedes or his Saxons), and had a knack for adapting himself to circumstances, a survival trait in turbulent Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. And, of course, Napoleon's harsh treatment of him comes back to bite the Emperor in the ass in a few years, while Bernadotte's descendants are still crowned heads in Europe.

When Bernadotte was mentioned, I was wondering what convinced the Swedes to make him their king. Did he look good in an ermine cape or something?

He was also chosen because he was 1) not connected to the old dynasty who had reinstated absolutism in the coup of 1772, 2) it was hoped that his military leadership and connection to Napoleon could help Sweden to regain Finland. It did not turn out as planned. He instead presided over an era of peace, cautious liberal reform, economic consolidation and investment in education and infrastructure. His reign is when Sweden transitions into a more peaceful nation.

Posts: 2,100

Threads: 12

Joined: Oct 2015

(March 30th, 2023, 15:26)chumchu Wrote: (March 30th, 2023, 11:36)Herman Gigglethorpe Wrote: (March 30th, 2023, 09:03)Chevalier Mal Fet Wrote: To be fair to myself, I was mostly giving Napoleon's perspective at that time. Bernadotte was no fool, but he was a bit of an uninspired battlefield commander. He could be vain, lazy, slow to take the initiative, and had bad battlefield instincts, but for all that he was brave, a good administrator, and well-intentioned. He was kind towards captured enemies, courteous towards foreigners (like Swedes or his Saxons), and had a knack for adapting himself to circumstances, a survival trait in turbulent Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. And, of course, Napoleon's harsh treatment of him comes back to bite the Emperor in the ass in a few years, while Bernadotte's descendants are still crowned heads in Europe.

When Bernadotte was mentioned, I was wondering what convinced the Swedes to make him their king. Did he look good in an ermine cape or something?

He was also chosen because he was 1) not connected to the old dynasty who had reinstated absolutism in the coup of 1772, 2) it was hoped that his military leadership and connection to Napoleon could help Sweden to regain Finland. It did not turn out as planned. He instead presided over an era of peace, cautious liberal reform, economic consolidation and investment in education and infrastructure. His reign is when Sweden transitions into a more peaceful nation.

Chumchu is likely better informed than I am, but my understanding is that it's as much as matter of the (extremely complex) internal and or Russian-focused Scandinavian politics as of anything else. I wouldn't take Wikipedia as a source of truth on anything too controversial, but lunchtime reading suggests the way that power shifted amongst the various parts there over time is fascinating.

It may have looked easy, but that is because it was done correctly - Brian Moore

|

![[Image: Bridge%2Bover%2BDanube%2Bbreaking%2Bby%2BMyrbach.jpg]](https://2.bp.blogspot.com/--2i3_jH9qcI/V0CkkCNA41I/AAAAAAAACVg/Ok3MI9Kep3Y1OFllvDvvsnSOyWBAd2qYQCLcB/s400/Bridge%2Bover%2BDanube%2Bbreaking%2Bby%2BMyrbach.jpg)

![[Image: Bridge%2Bover%2BDanube%2Bbreaking%2Bby%2BMyrbach.jpg]](https://2.bp.blogspot.com/--2i3_jH9qcI/V0CkkCNA41I/AAAAAAAACVg/Ok3MI9Kep3Y1OFllvDvvsnSOyWBAd2qYQCLcB/s400/Bridge%2Bover%2BDanube%2Bbreaking%2Bby%2BMyrbach.jpg)