I know the American Civil War doesn't strictly belong to your European plans here, but I would LOVE to see this kind of Historian's Corner on that (and your take on the AGEOD game in that time period as well)

|

Chevalier Plays AGEOD Let's Play/AAR

|

(April 18th, 2023, 14:35)aetryn Wrote: I know the American Civil War doesn't strictly belong to your European plans here, but I would LOVE to see this kind of Historian's Corner on that (and your take on the AGEOD game in that time period as well) Ironically, the ACW is my favorite time period in history, and probably the one I am most expert in. AGEOD's Civil War 2 is also how I got into AGEOD games, and it's probably their most polished. I saw ironic because it's the entry I'm planning to skip! I'm starting to get kind of burned out but i do want to finish To End All Wars. I will take a break for a while and come back to do Civil War 2 at some point, for certain. Historian’s Corner: September 1813 - Converging on Leipzig September arrived with Napoleon having gained no ground at all. He had won a smashing victory against a larger army at Dresden, only to have it completely undone in the space of a week by reverses on all other fronts.  French soldiers drowning in the swollen Katzbach, August 1813 Clearly, he needed to regroup and re-evaluate his strategy. With Schwarzenberg reeling in retreat back over the Bohemian mountains (even if he, uh, was completely overrunning Vandamme’s corps as he did so), the moment was ripe for another good ol’ drive on Berlin. He placed Ney with some reinforcements in charge of Oudinot with orders to sort out the mess on the northern front. Why he didn’t summon his most reliable marshal, Davout, from where he was wasted defending Hamburg, I don’t know. After signal service in 1805-7, 1809, and 1812, the Iron Marshal was sidelined for the entirety of this, the most vital of all of Napoleon’s campaigns. Anyway, Ney didn’t get all the reinforcements Napoleon promised, since Macdonald was retreating as fast as his feet could carry him and the Emperor decided he needed to shore that flank up instead. So, September found him rushing eastward once more, leaving only 2 ½ corps (St. Cyr, Victor, and the remnants of Vandamme’s command) at Dresden. Blucher retreated, again. Napoleon was seriously pissed off now, but there was nothing he could do. The allies refused to face him in a standup battle but kicked his subordinates’ asses anywhere he wasn’t. Word came from St. Cyr - as soon as Napoleon hied himself off to the east, Schwarzenburg had reversed course and was barreling down on Dresden, again. Napoleon rushed back to that town on September 8, and immediately the coalition army reversed course and ran the hell away, again.  Berlin front in the autumn 1813 campaign, showing Grossbeeren and Dennewitz. Note Torgau, on the Elbe, and Leipzig, in the south - both will be significant soon. While Napoleon was ping-ponging between Dresden and Silesia, trying desperately to catch one army to beat it without his other front collapsing entirely, Ney led his men straight at his old colleague Bernadotte at Dennewitz on the northern front - and promptly got his ass kicked, too. The bravest of the brave had plunged into the fighting, personally, sword in hand, which is a commendable example were he not the general commanding and the headless French forces had been routed by the less heroically courageous but more level-headed Bernadotte. Ney was forced to retreat to Torgau, on the left bank of the Elbe, and defend there. The weather turned muddy in September. Rains fell on the hard-slogging Marie-Louises, as the boys trudged back and forth across Saxony seemingly without end. Roving Cossacks raided French communications constantly. Bernadotte advanced against Ney. Schwarzenburg advanced against Dresden. Blucher advanced from the east. Napoleon turned now this way, then that, at bay - unable to come to grips with any of his enemies, unable to hold any of them off without his personal presence. The Trachenburg plan was wearing him down, as bit by bit the teenage conscripts’ endurance gave out and they dropped away from the army. The army was starving, as the food convoys could not struggle up the muddy German roads through the Cossacks, nor could it endlessly forage in the same country it was marching up and down in. Through battle, desertion, and disease 150,000 French soldiers had been lost over the month, with 50,000 more in hospital. By 24 September, Napoleon concluded that only a withdrawal to the near bank of the Elbe could save his army. He still had 260,000 men, but he could not endlessly march them and wear them out - he had to contract the front and hope the coalition screwed up enough to give him a good shot at one of their armies. The same day, the strategic situation transformed when Bennigsen’s fresh army of 60,000 newly-trained men arrived from Poland, taking over for Blucher in the area of Silesia. That in turn enabled Marshal Vorwarts! to make a flank march of his own, shifting north and west to join Bernadotte’s Army of the North and put some steel in the cautious Crown Prince’s spine. Schwarzenburg and the coalition monarchs in Bohemia meanwhile decided to strike not at Dresden, but to shift their blow to the west, towards the base of Napoleon’s communications at Leipzig. Once Blucher met up with the Crown Prince of Sweden, the combined army moved down to the Elbe and seized a bridgehead downstream from Torgau, at Wartenburg, on October 3. Coalition leadership decreed that the rendezvous point for all armies would be “in the camp of the enemy.”  Schematic of the final moves in the German campaign, as the coalition shifts around both Napoleon’s flanks to threaten his base at Leipzig. Napoleon, falling back west towards Leipzig, now had the better part of 250,000 men between a coalition army of 140,000 (the Army of the North) and one of 180,000 (the Army of Bohemia). If he could catch either one, he could beat it before the other came up in support. But catching it was the trick. He ordered Murat with 3 corps to hold off Schwarzenburg in the south as long as he could, while speeding north with the rest of his army to join Ney and force a battle against Blucher/Bernadotte. Fatefully, he left St. Cyr with his entire corps to hold Dresen, instead of abandoning his base there to contract everything back to Leipzig.  Map view as Blucher joins Bernadotte at the Elbe, Napoleon coming up to Ney’s aid. On 9 October, the Emperor whirled north, coming up behind Blucher and Bernadotte as they moved beyond the Elbe. Bernadotte, ever-cautious, promptly ordered a dignified scuttle back behind the river, but Marshal Vorwarts! disobeyed orders and took his army even further west, scooting across the nearby Saale river just ahead of Napoleon’s vengeful columns. Bernadotte had no choice but to order his army to conform to Blucher’s movements, and so the fiery Prussian dragged Bernadotte kicking and screaming towards the decisive moment. With no real light cavalry, Napoleon had no idea where the two armies had run away to, to his considerable frustration.  Blucher and Bernadotte slip away, Napoleon must cover Leipzig. The situation was growing serious. He could not pursue Blucher with Schwarzenberg bearing down on Leipzig - lose that city and he’d be cut off in Saxony and his entire army destroyed. But if he swung south against the army of Bohemia, then they would scuttle back to the safety of the mountains and the Army of the North could come down on Leipzig. Through the second week of October, Napoleon waited to see where he could concentrate - north or south? Murat fought an excellent delaying campaign against Schwarzenberg, bloodying the Austrians even in the face of considerably superior numbers. Meanwhile, he was athwart Blucher and Bernadotte’s communications, and while Bernadotte desperately wanted to retreat back over the Elbe, Blucher, with his hatred of Napoleon, his patriotism, and his distaste for retreat, refused. Instead, damning his communications, he set off south for Leipzig himself. Now, Napoleon had no choice but to concentrate everything he could on Leipzig, in one last desperate effort to beat one of the enemy armies before the other could come to its assistance. Murat was still fighting south of that city against Schwarzenberg’s advance; now Napoleon needed to speed to his aid. He put his corps on the road, writing, “All my army will be putting itself in motion; all of it will have arrived [near Leipzig] by the morning of the 14th, and I shall be able to fight the enemy with 200,000 men.” The whole of Europe’s armies were now converging on a single battlefield - Leipzig. The allied monarchs could feel the weight of the moment. They were to a man nervous about finally taking the Ogre on in person, but Blucher was emphatic, writing to them on 13 October: “The three armies are now so close together that a simultaneous attack against the point where the enemy has concentrated his forces might be undertaken.” Over half a million troops - Swedes, Prussians, Austrians, Russians, Saxons, Poles, Dutch, Italians, and of course French, were within a day’s march of the little town as the sun set on 14 October. The next day, Leipzig - the Battle of Nations - would begin.  The Battle of Leipzig, 16 - 19 October, 1813

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

[b]Historian’s Corner: October 1813 - The Battle of Nations

Leipzig is sometimes called “The Battle of Nations.” It was the largest battle in European history before the 20th century - over half a million men from a dozen nations engaged. There were French, of course, and Russians, Prussians, and Austrians. But there were also huge numbers of Poles fighting alongside the French for the dream of an independent Poland, there were Saxons, Dutch, Italians, and even some lingering Portuguese and Spanish soldiers impressed into the Army of the Elbe. There were Czechs and Croats, Slavs, Serbs, Magyars, Bosnians, and Ukrainians with the Austrian army, and Cossacks, Georgians, Armenians, Finns, and Balts with the Russians. Sweden was present - even a small British troop of rocketeers were part of the coalition. Damned near every nationality in Europe was represented.  The battlefield at Leipzig is radial - a vast circle sectored by a few rivers and streams, creating a massive concentric battle centered on the city itself. The Pleisse and Elster join at Leipzig, creating a marshy, inaccessible bottomland between them just west of the city. The main road from Dresden towards the Rhine runs through the city and then along a high embankment through this area. Beyond the marsh are two roads running through flat, open terrain for a few miles. South of the city, the Pleisse runs southeast, away from the southerly flowing Elster, creating a second sector. To the north, the Parthe river runs to the northeast, creating a northern sector of broad, flat terrain and many good roads running towards the Elbe. The final sector is to the east and south, lying between the Parthe and the upper Pleisse, dotted with hills and low ridges, the broadest approach to the city but easily defensible terrain. The city itself was ringed by a low medieval wall. Ney with his northern force was deployed astride the northern sector, between the Parthe and the Elster, facing Blucher’s Prussians, who had come on despite Bernadotte’s protests - the Swedish prince was dragging his feet some miles away. Napoleon took personal command with his reinforcements over Murat’s southern force in the arc from the Parthe to the Pleisse, facing the massive Army of Bohemia - Prince Schwarzenberg in official command, but with the Tsar, Emperor Francis, and King Frederick William all peering over his shoulder and shouting ‘suggestions.’ Napoleon planned an offensive battle, obviously. The Allies were approaching over a broad front and would have difficulty concentrating their entire force at once. The best French chance for victory was to hit them in detail. So, Murat with VIII, II, and V Corps and the cavalry, about 37,000 strong, would pin the Army of Bohemia in front, while Napoleon threw XI Corps and a further cavalry corps around their right flank, 23,000 men. Then, the Guard, IX Corps, and two more cavalry corps (plus either Bertrand or Marmont’s corps drawn from Ney) would be hurled forward to break the allied army and send them into headlong retreat. Then to whirl on Blucher and defeat the irritating marshal at last. Meanwhile, Ney with III, IV, VI, and VII Corps would hold the north. Overall, there are 177,000 French present on the field, and 120,000 of them would be thrown at the Army of Bohemia. The French spent the whole of 15 October moving into position. Schwarzenberg initially proposed a plan so bad he was practically accused of treason, wanting to send the main weight of the coalition attack up the far side of the Pleisse to cut Napoleon’s retreat - in other words, marching 50,000 of the allies’ best troops into a damned swamp. The Tsar himself intervened and demanded a new plan. Blucher was to move on Leipzig from the northwest, of course, and 19,000 men were to move to the high road to cut the French retreat. The main offensive would be in the south, where the army of Bohemia would move forward en masse under Barclay’s command. Barclay in turn delegated the actual conduct of hte assault ot General Wittgenstein, who dispersed the assaulting formations over a massive 6-mile front.  The Battle of Leipzig, 16 October 1813 In an effort at simplification, I’ll cover the massive fighting on October 16 sector by sector, as all three armies present launched enormous attacks on each other and fighting raged in every corner of the battlefield. In the north, Marmot’s VI Corps was initially slated to march to the southern front to aid Napoleon. The Emperor, deprived of cavalry, reckoned that Blucher had already slipped south to join up with the main army and that Bernadotte was days away - but in actuality the Prussians were already on the field and deploying to attack Ney (Bernadotte was days away, though). Blucher stormed forward and launched a furious assault against the town of Mockern, which anchored the French line from the Pleisse eastwards. Instead of going to Napoleon, then, VI Corps was diverted by Ney to reinforce this key strongpoint and fighting raged there all through the day.  Instead, Ney sent Bernard’s IV Corps south to take Marmont’s place in the grand attack Napoleon was preparing. But before this corps could get going, crisis on the western front (the army’s escape route through the village of Lindenau) caused Ney to divert this corps, too, to the relief of the west. Instead he sent only two divisions of III Corps, leaving himself to hold the north with a thin screen as best he could. There was a lull, however. After the early morning battles, Blucher became uncharacteristically cautious - he had little idea how much of Napoleon’s force was facing him, and Bernadotte would not be up before the 17th. He didn’t launch his main attack until 2 pm. But it was a doozy when it came - the thunder of Blucher’s guns distracted Napoleon even as the action in the south was climaxing. The heroic Poles defending the village of Mockern held as long as they could, and charge and countercharge flowed up and down the streets of the tiny hamlet. Houses burned and smoke choked the entire battlefield. Ney grew so concerned that he recalled even the two divisions of III Corps he had sent to Napoleon, and so the Emperor received no reinforcements all that day. The fight for Mockern took the whole of the day on the northern front. Blucher stubbornly put in attack after attack, refusing to accept defeat. One division would reel back in bloody ruin, only to be replaced by another. The French would pursue a routed Prussian division - only to be overrun in turn by the entirety of the Prussian cavalry reserve. As evening came, the French were driven out of the village, outnumbered and outfought. To the west, at Lindenau, an Austrian corps under Gyulai was tasked with coming up from the south and cutting the road, sealing off Napoleon’s line of retreat. Fighting there began at about half past ten, but soon Ney sent IV Corps from the northern sector, and by noon the situation here was resolved. Bertrand was tied down, though, and unable to support the massive brawl in the south. In the south, the allied assault pre-empted the French. Multiple corps surged forth, albeit poorly coordinated and extremely dispersed. Murat’s holding force surged forth to meet them, and all morning fighting in the south centered on the little village of Wachau. Multiple corps on both sides were drawn into the fighting, a brutal slugging match of crashing muskets from densely packed battalions fighting at close range, artillery whipping roundshot and canister through the ranks, cavalry surging to and fro around the edges of the formations. By 11 in the morning, the coalition had managed - just - to push the French out of the village, but their momentum was largely spent.  Austrian column of assault In response Napoleon cursed the absence of Marmont and Bertrand, but assembled a grand battery of 150 cannon to batter the coalition center. Napoleon would advance on a broad front - Poniatowski on the right holding the line of the Pleisse (one column of the enemy attack had shoved itself into that swampy dead ground), Victor on the right center shoving past Wachau, Lauriston on the left center, and Macdonald on the far left to outflank the coalition. Augereau and Mortier’s corps would be passed through the gaps between the forward corps to maintain the attack. Behind the bombardment, Murat would take 12,000 horse right into the allied center and carve a path through their army. The southern army swept forward just past noon, but Macdonald made less progress than expected - IV and VI Corps might have made the difference but they were pinned down elsewhere. At 2, as the attack ground forward, Napoleon decided he could wait no longer and unleashed his main blow - the grand battery opened and Murat pounded forward. At the same time every single corps regrouped and renewed its efforts. The allied center practically disintegrated under the onslaught, reeling backwards before reserves could come up to stem the bleeding. Murat’s cavalry poured in, sabering their way practically to the Tsar’s command post itself - the imperial guard cavalry actually got their swords wet, as a whirling cavalry melee erupted beneath Alexander’s nose. By 3:30, though, the fresh allied cavalry had stabilized the situation, and the crisis passed. The Army of Bohemia was battered but not broken.  Marsh and forest fighting on the French right, 16 October 1813 As the afternoon wore into evening, the coalition columns over in the swamp on the allied left finally forced their way over the Pleisse and hit Poniatowski’s corps. Fresh reserves came up and piled on, and soon the Polish prince was in serious peril. Napoleon put in the Guard and what reserves he had of III Corps (most of it was in the north) and stabilized, and the sun slipped below the horizon on the first day’s fighting at Leipzig. It had been a draw. 25,000 Frenchmen would never see home, nor would 30,000 coalition soldiers. The evening of the 16th, Napoleon began to prepare to retreat to the Rhine. He knew that although honors of the day had been even, he had needed to win a decisive victory against one or the other of the allied armies. WIth Bernadotte hastening to catch up to Blucher and Bennigsen’s fresh army coming in from the east, the odds were increasing against the French, and by the 18th the Coalition would have more than 300,000 soldiers against less than 200,000 French. But then he made one of the final mistakes of his career: in the hopes of more reinforcements reaching him, or allied nerve cracking, he opted to hold through the entire day of 17 October, instead of retreating. He contented himself to abandon most of his perimeter and pull to a shorter line closer to Leipzig. The allies, meanwhile, were content to wait through the day, as Bennigsen and Bernadotte at last trickled in. A series of six converging, sledgehammer attacks were prepared from all directions to fall upon the city. The decisive battle was set for 18 October.  The fighting on 18 October The fighting on the 18th was confused and heavy. Like every battle since the Wagram campaign, there was no finesse, no maneuver, just straight-ahead slugging, corps against corps. Marshal Poniatowski - the only non-Frenchman to be given the marshal’s baton by Napoleon, promoted in the wake of his tough performance on the first day - still held the French right hard by the Pleisse, where he fended off Austrian corps. In the west, IV Corps again smashed aside Gyulai’s corps, and Bertrand was sent to secure the bridges over the Saale to the west for the impending withdrawal to the Rhine. To the north, nothing much happened in the morning since Bernadotte was characteristically dragging his feet. Finally, to the east, Macdonald and Reynier’s newly arrived corps linked up with Ney to complete the French perimeter, facing Bennigsen’s advent on the field.  Fighting outside Leipzig, 18 October 1813 After noon, the fighting raged all around the perimeter, but the French held - except in the east. Bennigsen’s fresh troops put a severe dent in the French line here, and the French kept the line intact only with difficulty. Just as they seemed to get a grip on the situation, Bernadotte at last slouched onto the field and put in his own attack, while Bennigsen came in again. The northeast began to collapse, and Napoleon ordered the Imperial Guard into action. Ney, still in overall command in the north, began to pull back to shorten the line, when disaster - all of the Saxons in his army deserted! Saxony joined Bavaria, Wurtemburg, and other wavering German states in defecting from Napoleon, and two entire brigades went over to the coalition, leaving a gaping hole in Ney’s line. A new attack came in just before sunset, and by the time the battle petered out in darkness the French had been driven practically into Leipzig itself. Clearly, it was time to go. In the early hours of 19 October, the French army began to withdraw, tacitly conceding the German campaign that had begun back in April. Battalion after battalion filed over the single bridge in Leipzig, while the perimeter quietly shrank back to the town walls itself. VII, VIII, and XI Corps were designated the rearguard, meant to hold the town through the 19th so the rest of the army could escape. Napoleon still had over 150,000 men, even after battle casualties, and might yet make a good stand on the Rhine. At 7 am, as the sun came up, the Coalition cottoned on to what was going on. Napoleon stalled them a bit longer with negotiations for peace, and it wasn’t until ten that the Coalition began attempting to come over the walls to give the French a stern talking to. Napoleon crossed the bridge at about 11, and while the army was beginning to show signs of disorder, it appeared he was going to bring off a triump to rival the crossing of the Berezina the year before.  Street fighting in Leipzig, 19 October 1813 Disaster for Napoleon at Leipzig came from the dumbest fucking accident. For whatever reason, the planned demolition of the single, slender bridge out of town was delegated to an unreliable general, who in turn delegated to a colonel, who made a command decision that some of those bullets were coming entirely too close, hey? and used privileges of rank to delegate to a miserable corporal. At one in the afternoon on 19 October, as the army was calmly marching battalion by battalion over the bridge, while Oudinot’s rearguard was holding magnificently at the walls, this goober panicked at the sight of a few enemy horsemen that appeared on the far bank, concluded the bridge (which was packed full of French troops) was about to fall into enemy hands, and lit the fuse.  Napoleon retreats from Leipzig, as the bridge explodes in the background. Hundreds of men went up with the bridge, fragments of wood and stone whirling through the air and plunging to earth all up and down the river. At a stroke, 30,000 men were cut off in the city, hundreds of guns and stores were lost. The rearguard fought into the afternoon, but outnumbered 10:1 was eventually forced to surrender. The battle at Leipzig cost the allies 54,000 killed, wounded, or captured. The French had lost about 30,000 battle casualties, plus the defection of the German vassals, but then the disaster of the bridge doubled their total and cost the army its remaining heavy equipment. Already shorn of cavalry, now the French army would be required to fight without artillery, too. Politically, the defections of Bavaria and Saxony set off a chain reaction that ended in the disintegration of the Confederation of the Rhine, as each state in turn backed the winning horse. Napoleon’s entire empire beyond the Pyrenees and the Rhine lay in ashes, after Leipzig. The Emperor made it back to that river safely enough. On 23 October 100,000 ragged but fighting-fit survivors made it to Erfurt, regrouped and re-equipped, and set off again for Frankfurt on the Main. Cossacks were a nuisance and Blucher had set off on a northerly parallel route, while the Army of Bohemia sluggishly came on in the east. The Bavarian Wrede (patriotic member of the coalition since 5 minutes ago) tried to block the retreat at Hanau with 45,000 men and got run right over by the retreating army (“I made him a Count, but could not make him a general,” Napoleon wearily commented) on 30 October. After straggling and losses from disease, about 70,000 survivors of the army reached the Rhine on 2 November. Close on their heels came the four Armies of the Coalition - the North, Silesia, Bohemia, and Poland. There would be no winter pause in campaigning this year. They were determined to put an end to the Corsican Ogre once and for all.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Historian’s Corner: Winter 1814 - November 1813 to January 1814

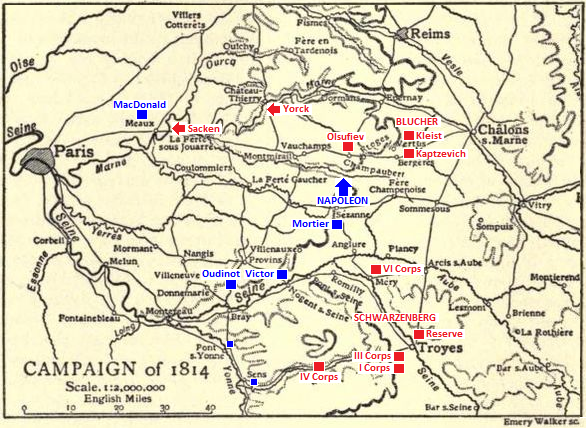

Situation 1 January 1814 The military situation for anyone except Napoleon looked hopeless by December, 1813. The Emperor had maybe 80,000 soldiers to pit against the 300,000 in the four coalition armies on the Rhine. To the south, Wellington’s 120,000 Anglo-Portoguese-Spanish soldiers had forced the defenses of the Pyrenees and were invading southern France. The beleaguered garrisons along the Vistula, Oder, and Elbe were surrendering one by one. Eugene in Italy was being driven back by 75,000 more Austrians. Holland and Belgium were seething with revolt, and the people of France itself were exhausted from two decades of war, blockade, and hardship. The Emperor issued appeals to French patriotism, calling on the spirit of the levee en masse of 1792 - now as then the country was in danger. He released the Pope from house arrest, offered to put Ferdinand of Spain back on his throne, and summoned all the reserves left in France to make one final effort to resist. He hoped that he would have until March or April 1814 to fully prepare himself. The Coalition must be exhausted after the German campaign; they would need time to integrate the new German allies into their command structure, and their leadership was divided amongst itself. All that should buy him time. The three monarchs in the Coalition camp were divided, it is true. Francis of Austria was Napoleon’s father in law, and destroying the French Empire would not only weaken his family but strengthen the Prussians and the Russians. Bernadotte privately was hoping to be offered the throne of France himself, if he wasn’t too aggressive against Napoleon. Frederick William of Prussia wished to avoid prolonging hte war. Britain wanted to maintain the balance of power on the Continent and avoid strengthening Russia. Tsar Alexander, though, wanted to drive on Paris in revenge for Moscow, as did Blucher and the Prussian soldierly, bloodthirsty and eager to topple Napoleon forever. In November, as the armies arrived on the Rhine, the allies met in Frankfurt to hash out their differences. The resulting basis for peace, the Frankfurt treaty, was rejected out of hand by Napoleon. It required France to be reduced to her natural frontiers - the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Rhine. It meant the end of the kingdom of Italy, the reversal of everything Bonaparte had accomplished since 1796. He didn’t think he was beaten, not yet. On December 22nd, the first coalition armies began crossing the Rhine. In order to feed their enormous armies, the Coalition was forced to split up the massive force that had triumphed at Leipzig. Bernadotte’s Army of the North was dispatched to keep Davout penned up in Magdeburg and invade the Low Countries, raising revolt there and rendezvousing with a British expedition. Blucher’s Army of Silesia, reinforced to 100,000, would invade the central Rhine near Coblenz. The Army of Bohemia with all the monarchs would head for Colmar and the upper Rhine. Then, they would push to make contact with Wellington on the left flank, and all forces, 400,000 strong, would converge on Paris by the middle of February, 1814.  Episode from the Campaign in France, 1814 There were only skeleton forces to oppose this massive armament. Napoleon had not yet even partially rebuilt his formations shattered in the German campaign. No recruits came to the colors. The national guard was called up, but few men came. Most French by this point were tired of dying for la gloire of their emperor. Even Cossack raids did not rouse a popular insurrection against the invaders, which Napoleon had been banking on after his own experiences in Spain and Russia.  Situation by the end of January, 1814 Schwarzenberg crossed the Rhine unopposed via Switzerland and Strasbourg (the same invasion route my own Austrians took in our 1809 campaign, I might note), then crossed the Moselle at Nancy as Marshal Victor fell back before the Army of Bohemia’s overwhelming numbers. By January 17, the French army, such as was left of it, was behind the Meuse, which Blucher’s Army of Silesia crossed on 22 January. By 23 January he had even reached the Marne - 75 miles into France in only 9 days. Schwarzenberg was more cautious, but he reached the Langres Plateau by the 17th as well and halted there for a week through another round of peace negotiations. However, he was only two day’s march from linking up with Blucher’s northern column. Napoleon could only leave Paris on 25 January, and on the 26th of that month he once more took the field against the might of the Coalition. His overriding concern was to defend Paris at all costs (still the obsession with national capitals! Why Napoleon never learned from experience, I don’t know - perhaps too enamored of his own considerable genius? Didn’t think he had anything to learn? It’s such a weird blind spot in an otherwise brilliant mind. He would have been better served in a hit and run campaign against Allied communications rather than an all-out defense of the capital), and secondly to prevent the reunion of Blucher and Schwarzenberg’s armies. He had perhaps 40,000 men available to do this, plus another 40,000 static troops holding vital points. Against him, Schwarzenberg had 150,000 men in 3 columns approaching from the southeast, moving down the river Aube towards Paris. Blucher was to the east, coming from Metz, with another 100,000, although half of those were tied up in sieges at this point. More armies were invading the Low Countries, but that was a problem for Tomorrow Napoleon, not Today Napoleon.  The campaign in France, 1814. Sorry about Napoleon’s frenzied marches clogging up the map - the main thing I want to point out is the rivers, all running more or less in arcs from the southeast to the west, converging on Paris. The rivers were both lines of communication for the Allies trying to move down them and obstacles that blocked movement unless you held the appropriate bridge. The campaign can be summarized as Napoleon bouncing between the two main armies - Schwarzenberg to the southeast and Blucher to the east - halting whichever one he faces but losing ground to the other, in accordance with the Trachenberg Plan. The movements today are at lower right center. Napoleon first hustled off to face Blucher, who was closest to Paris. Marshal Vorwarts! had allowed his troops to become considerably spread out, perhaps thinking all the fight had gone out of the French, and had only about 25,000 troops in his main body. The Emperor hoped to catch him halfway across the Marne. Unluckily, though, he arrived a few hours too late, catching only the tail end of the Prussians as they headed south to join up with Schwarzenberg. Napoleon pursued to Brienne, again catching the rearguard near Brienne, bloodying a few Prussian noses, but Blucher, fully aware that Napoleon was on his heels, was rapidly concentrating. A copy of Napoleon’s orders had been captured by the omnipresent Cossacks, and in the nick of time Blucher got into a defensive position at Brienne on 29 January. Ney and Victor pitched into the Prussian positions around the little village, which was soon riddled with musketballs and cannon shells. Napoleon narrowly evaded capture at one point by a party of Cossacks, while Blucher and his chief of staff Gneisenau had to scramble out the back gate of a chateau even as French troops kicked in the front door. Brienne proved a French tactical victory but Blucher was forming up and had been joined by the Army of Bohemia.  La Rothiere campaign, 26 January - 1 February, 1814 Over the next two days, in heavy snowfall, Napoleon tried to work out where his enemies were. He knew they were in the south in some strength, but were they concentrated? Turns out, yes, yes they very much were. Blucher and Schwarzenberg came up on February 1 towards Brienne from a little hamlet to the south, La Rothiere, and launched a powerful attack on Napoleon with 110,000 against possibly 40,000 French.  The Battle of La Rothiere was a hard-fought affair despite the French disadvantage in numbers. The infantry tenaciously clung to the village in the face of intense coalition assaults, while on either side cavalry swirled around each other and artillery gleefully poured fire into the masses. A blizzard raged all day, obscuring visibility and creating miserable conditions.  La Rothiere, 1 February 1814 It seemed the French might hold the village all day, but as the shadows lengthened around four, suddenly coalition reinforcements poured onto the field - a fresh corps entered on the French left and another came up through the center and renewed the attack on the village. There was desperate fighting in the snowy woods and fields on the left as a scratch force of Young Guards held back the onslaught, while the last French reserves drove the allies once more out of La Rothiere, and as night fell Napoleon skillfully extricated his men from the untenable position. Two days and two nights the French retreated, and thousands of conscripts dropped from exhaustion and exposure. 6,000 Frenchmen had died in exchange for about the same number of coalition troops, and thousands more and 50 guns were lost in the retreat. The allies announced a fresh peace conference while they tried to sort out their differences, while the 30,000 survivors or so of Napoleon’s little army sought what food and shelter they could. The Emperor’s fortunes had reached their lowest point, but he wasn’t beaten yet, not by a long shot. The next month would be acclaimed by some historians as the finest campaign in Napoleon’s long career.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Historian’s Corner: February - 1814 - the Six Day’s Campaign

In the wake of their victory at La Rothiere, the allies grew complacent. Had they not just beaten Napoleon, again, in open battle? The man was not invincible, and their forces were so overwhelming that as long as they didn’t blunder catastrophically, there was no way they could lose! The allies proceeded to try their best to lose. Schwarzenberg was worried about his lengthy supply lines back towards Austria, and the large number of French troops to the south, and nervously began to edge to the south. Blucher, meanwhile, was disgusted at the Army of Bohemia’s mismanagement of La Rothiere (only Schwarzenberg’s sluggishness in supporting him had allowed Napoleon to escape, the marshal felt). So Marshal Vorwarts! cried “Vorwarts!” and the Army of Silesia moved off to the north, seeking the remnants of the French army so he might destroy it. Once again, the Prussian allowed his men to begin spreading out over the countryside.  Suddenly, Napoleon dropped like a thunderbolt onto the middle of the Army of Silesia. 20,000 men led by the Emperor himself erupted into Blucher’s center at Champaubert. At 10:00 in the morning of 10 February, the last army between Blucher and Paris suddenly attacked one of Blucher’s isolated corps, a Russian force under one General Olssufiev - 5,000 men. Barely a thousand escaped. Napoleon, after vacillating for a week following his defeat at La Rothiere, had learned of the growing gap between Blucher and Schwarzenberg. Slipping his army into that gap, he had crept along past Blucher’s forward positions, and then made his surprise attack on Olssufiev. Suddenly he was planted right smack in the middle of Blucher’s widely separated corps, able to concentrate on each in detail. Blucher desperately sent out orders to regroup, but Napoleon was between his corps.  Situation after the Battle of Champaubert - Napoleon’s 20,000 army in the middle of 3 times their number of enemies. The next day, 11 February, Napoleon erupted out of the woods at Montmirail, falling on a second Prussian corps. Their commander, General Sacken, was attempting to obey his orders to rejoin Blucher when he ran smack into Napoleon, marching hard west from Champaubert. Napoleon had lost some men to mud and the pace of his advance, but he was in the midst of 60,000 Prussians and couldn’t afford to give anyone time to regroup. All morning, Sacken’s 18,000 tried to break through the roadblock Napoleon’s 10,000 threw up in the road, while the Emperor waited for his reinforcements to reach the field. The young French conscripts threw back attack after attack, while the nearby corps of General Yorck, with another 18,000 men, hurried south to Sacken’s aid.  Battle of Montmirail, 1814 Yorck took his time, and Mortier arrived with the Imperial Guard first. Napoleon wasted no time - Ney was placed at the Guard’s head and led an assault that broke Sacken’s flank, and the Emperor poured in his last cavalry reserves. The men of Sacken’s corps decided that they’d rather be anywhere other than Montmirail, and the entire force dissolved into flight. Then Napoleon turned and bopped Yorck’s leading formations on the nose, and that force, too, withdrew.  Day 2 of the 6-day Campaign: Montmirail On 12 February, the remaining Prussians skedaddled back over the Marne, nipping ahead of Macdonald’s pursuing forces, and Napoleon needed a full day to get bridges in place to pursue them. Blucher got word that the Army of Bohemia had bestirred itself at the news of Napoleon’s latest exploits, and came on to attack and pin Napoleon down. The Emperor wasn’t done yet, though, and he threw himself at Blucher head-on on 14 February at Vauchamps, the third battle in five days. Grouchy skillfully led his small cavalry force and turned Blucher’s flank and the Prussians were again put to flight. The French cavalry got astride his line of retreat, but the doughty old marshal was able to savagely fight his way clear of the trap and continue his expeditious move to the rear with all haste. The Prussians left behind 7,000 men on the field. With 30,000 men Napoleon had launched an offensive against an army more than double that number, had beaten it three times, inflicted 20,000 casualties for less than 10,000 losses, and captured dozens of guns. It was Napoleon at his best. But it wasn’t enough. Blucher was shaken up but still combat effective, and Napoleon could spare him no more time - the Army of Bohemia had lurched into motion to the south, and he desperately needed to head it off. Schwarzenberg was already getting nervous again, though. The French populace was beginning to turn on the invaders, for one - columns were harassed and sniped at, foraging parties ambushed, the rumblings of a popular war like Russia or Spain. For another, his communications were dangerously exposed to gathering French forces at Lyon to the south. Finally, there was the word that Napoleon had routed Blucher and was now speeding south to confront him. All in all, no, no, things were not good for the 150,000 men of the Army of Bohemia, Schwarzenberg decided. By February 17 he had already issued orders to pull in his outlying corps and fall back a bit. Napoleon left Montmirail on the 15th. He piled his infantry onto requisitioned wagons and carts, and in 36 hours moved 47 miles, arriving late on the 16th near Schwarzenberg. He summoned all the militia and men he could from the Paris defenses, and with French morale rising in the wake of the victories against Blucher men flocked to the colors. He had nearly 60,000 now to confront the Army of Bohemia. On the 17th, his cavalry swarmed over some of Schwarzenberg’s outlying corps, but Marshal Victor’s columns were laggardly and slow - a maneuver meant to cut Schwarzenberg’s retreat arrived too late and ran head on into prepared defenses instead at Montereau. Victor was relieved for his incompetence. Moving south on the 16th The battle of Montereau, on 18th, saw the French storm this town on the Seine, routing an entire corps, and the vital bridges fell into Napoleon’s hands. By the end of the day, the coalition had lost 6,000 men and 15 guns. Only due to Victor’s slowness did Schwarzenberg safely get to the safe bank of the Seine, away from Napoleon. The Emperor, heady with victory, rejected a last offer of armistice on less than suitable terms, and in so doing probably sacrificed his last chance of survival as ruler of France. Meanwhile, Schwarzenberg retreated for Troyes and summoned Blucher to join him as their only chance to face Napoleon’s army. He believed the Emperor was at the head of 180,000 men (he had 74,000 in reality) and that his communications with Austria were in serious danger. He continued his retreat past that city, which Napoleon reached on the 24th.  Napoleon and his marshals in France, spring 1814 In the space of a month since taking command on January 26th, Napoleon had fought half a dozen small battles, won all but one of them, and driven both enemy armies in turn into retreat. In operation terms, the campaign thus far was one of his best. But the realities of grand strategy were against him - there were too many enemies, more columns closing in from the north and from the south, and the armies he had fought were hardly destroyed, just roughed up a bit. In fact, by the time he was received in triumph in Troyes, Napoleon had scarcely more than a month left on his throne.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Historian’s Corner: March 1814 - the Fall of Napoleon

On March 1, another conference of Coalition leadership ratified all the monarchs’ intention to continue the war against Napoleon for twenty years, if need be. No separate peace was to be signed. Britain pledged more subsidies, and one final offer was made to Napoleon - immediate cease-fire and peace based on the frontiers of 1791. Napoleon once again rejected the terms. Blucher began the final phase of the campaign by renewing his drive on Paris almost immediately. He had been joined by fresh reinforcements from the campaigns in the Low Countries, and was determined to reach the French capital or die trying. He jumped to the north bank of the Marne and blew the bridges behind him, Napoleon was frustrated and stuck on the wrong side of the river. His men’s morale was shaken after the Six Days campaign, but he was resolved to push on regardless. Vorwarts! He moved for the Aisne. The only bridge at Soissons was held by a French garrison, but the commander immediately decided that he had no desire to die for la gloire and surrendered practically before the Prussians arrived. Blucher escaped beyond the Aisne and linked up with the corps from the north, bringing his strength back up to 100,000. At the same time, Napoleon heard that Troyes had fallen, again, behind him - Macdonald could not hold the city since Schwarzenberg screwed his courage to the sticking place and came on again. “I cannot believe such ineptitude,” the Emperor raged. “No man can be worse seconded than I am.”  The campaign of Craonne and Laon. Well, nothing for it. He would have to beat Blucher (again), and then hurry south to beat Schwarzenberg (again), and then hope at some point a miracle happened, I don’t know. Anyway, he hurried after Blucher as soon as he got over the damned river, having to divert all the way to Berry from Soissons to do it. Soon enough on 6 March he came upon a rearguard at Craonne. Ney was ordered to dive in straight away, and the bravest of hte brave didn’t hesitate a moment. Good thing, too, since Blucher’s entire army was skulking on the far side of a ridge, waiting to pounce on Napoleon. The French came on so rapidly, though, that Blucher hadn’t quite readied his counterstroke yet. The next day Ney’s attack blundered when the marshal went in too early, before Napoleon’s intended double envelopment was ready, but the Prussian counterattack also fell to pieces in the marshy ground to the north, and Blucher disgustedly ordered a retreat a short ways to Laon. 5,000 men on both sides fell.  The Battle of Craonne, 6-7 March 1814 Now, Napoleon thought hte force he had just beaten was the rearguard of the Prussians, and even though he only had 40,000 to face Blucher’s 100,000 with, believed that he could harry him north on the road to Belgium a bit. So he hurried north to Laon, where he ran smack into Blucher again, waiting for him, on 9 March. Blucher thought he was facing 100,000 Frenchmen, and assumed the sharp frontal attacks he was facing from the 30,000 before him must be some kind of trap (thus the Prussians vastly overestimated the French even as the French vastly underestimated the Prussians). The cautious fighting lasted all day, dying down at 5.  Battles of Craonne and Laon, 7-10 March 1814 Marshal Marmont had been hastening up with his ‘corps’ (more of a division) to join the Emperor, and at sunset he put his men in bivouac on the far right of the French line, a few miles distant from the main body. Blucher sniffed this out, and launched a surprise attack at 7 pm that utterly routed VI Corps, the formation being saved from complete destruction only through a few strokes of luck. Blucher put his whole army in motion, trying to swing around Napoleon’s right and cut him off from Soissons. Napoleon only heard of the debacle at dawn on the 10th. Chance alone saved the French army. Blucher fell ill on the 10th, and Gneisenau was far more cautious. Napoleon coolly stood and invited attack all day, diverting attention from Marmont’s wreckage, and the Prussians, still suspecting a trap, pulled in their horns. As darkness fell Napoleon slipped away to Soissons. The two day’s fighting cost the French 6,000 and the allies another 4,000. A weary Napoleon wrote to Joseph (now prime minister in Paris since he was no longer King of Spain): Quote:I have reconnoitered the enemy’s position at Laon. It is too strong to permit an attack without heavy loss. I have therefore given word to fall back to Soissons. It is probable that the enemy would have evacuated Laon for fear of an attack but for the crass stupidity of the Duke of Ragusa [Marmont], who behaved himself like a second lieutenant. The enemy is suffering enormous losses; he has attacked the village of Clacy today five times - and been repulsed on each occasion. By mid-March, Napoleon’s armies both north and south were reeling in retreat. Two triumphant enemy armies lay on the Seine and on the Aisne, 200,000 men between them, and Napoleon ahd not 75,000 to face them with. Soult was being driven into Toulouse by Wellington, Bordeaux was revolting, Italy was teetering on the brink of total collapse, the Low Countries were in open revolt and the French were fleeing that area, and Davout still held Hamburg, deep in Germany.  Napoleon fought on. He swept eastwards, across the face of Blucher’s army on the far side of the Aisne, to Rheims, where he routed a Russian corps, inflicting 6,000 losses in exchange for 700 of his own. He swept south, towards Swarzenberg’s communications again. Once again Schwarzenberg (now sick with gout, so stressed was he) scuttled back to Troyes. Once again peace was offered, once again it was rejected. It would be a fight to the finish. Early on the 20th, Napoleon attempted to hit the Army of Bohemia’s communications at Arcis-sur-Aube. This blow would discomfit Schwarzenberg and hurry his retreat, giving the Emperor time to hurry north and stop Blucher’s latest lunge at Paris. He had miscalculated, though - Schwarzenberg once again found his nerve and abruptly swung about in his retreat, also coming at Arcis (where he found Napoleon, to his own considerable surprise). Napoleon had occupied the town early in the morning and was supremely confident that the allies were retreating - as at Laon two weeks before he was stunned to find the entire army coming at him. A mass of hostile cavalry abruptly swept in his pickets and then swept his handful of cavalry away, too. Marshal Ney led the defense and fought heroically, as usual, and only when the Guard itself rushed to the battlefield was the situation stabilized.  Napoleon rallies routing troops on the bridge at Arcis-sur-Aube, 20 March 1814 Napoleon himself was in the thick of the fighting, nearly being blasted to pieces by a howitzer shell (he later said he was disappointed it hadn’t killed him). By nightfall, the French held their positions at Arcis, and even a twilight cavalry charge drove back two divisions of allied cavalry. They still had no idea that they had repulsed only a part of the enemy army, not all of it, and the rest was massing to crush them in the morning.  Arcis-sur-Aube, 20-21 March 1814 By dawn on 21 March, Napoleon had less than 30,000 men at Arcis facing over 80,000 Coalition soldiers. Schwarzenberg was convinced that Napoleon had a hundred thousand men with him and his courage was fast trickling out, while Tsar Alexander did not approve of the offensive. It was not until 3:00 that the offensive at last began - and by that point Napoleon, whose eyes had bugged out of his head a little when he mounted the ridge outside town and saw the vast host gathered against him, had been retreating for hours. Oudinot led a heroic rearguard and kept the allies out of town for three hours, only blowing the bridge and pulling his men out at six pm. Another 7,000 combined casualties on both sides. The footsore army slogged north, back to the Marne - St. Dizier, in fact, which coincidentially was the same town they had tried to trap Blucher in back in January, 2 months of the most intense marching and fighting in any grognard’s memory ago. From there, Napoleon would continue trying to harass the enemy communications and drawing them after him. But by now they were sick and tired of Napoleon’s bullshit. Perhaps out of frustration, the Tsar intervened and with Blucher ordered the army to get their asses to Paris, come hell or high water. Let Napoleon do what he wanted to the communications, they would have his capital. Both armies moved out on 25 March, and on the 28th they rendezvoused for the third and last time at the very gates of the French capital. 22 years before, revolutionaries had chopped off King Louis’s head in that city. The combined monarchs of Europe had declared war in an effort to avenge that murder - and now, after two decades, fighting from Lisbon to Moscow, and hundreds upon thousands of deaths, they had at last reached their goal.  The Battle of Paris, 30-31 March, 1814 Marshals Marmont and Mortier led a staunch defense of the capital on 30 March, but at 2 am on the 31st it was clear resistance was hopeless, and they surrendered. Paris went over to the enemy. Talleyrand, former foreign minister, rallied a rump government ot his standard and declared Napoleon deposed. Bonaparte had reached the end of the road at last. After a half-hearted attempt to convince his marshals to march with him on the capital, he bowed to the inevitable. Marmont defected to the Coalition, Ney said the army would not march, and all over his position was collapsing. Napoleon on 6 April dictated the following from Fontainbleau: Quote:The Allied powers having proclaimed that the Emperor Napoleon is the only obstacle to the re-establishment of peace in Europe, the Emperor Napoleon, faithful to his oath, declares that he renounces, for himself and his heirs, the thrones of France and Italy, and that there is no personal sacrifice, not even of life itself, that he is unwilling to make the interest of France. On April 20th, Napoleon bid farewell to his Guard, the last soldiers by his side. Then, as King Louis XVIII was placed on the throne, he went into exile, ruler of the small isle of Elba. And that was the last that anyone ever heard of Napoleon Bonaparte.  Napoleon bids farewell to his guards, 6 April 1814

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

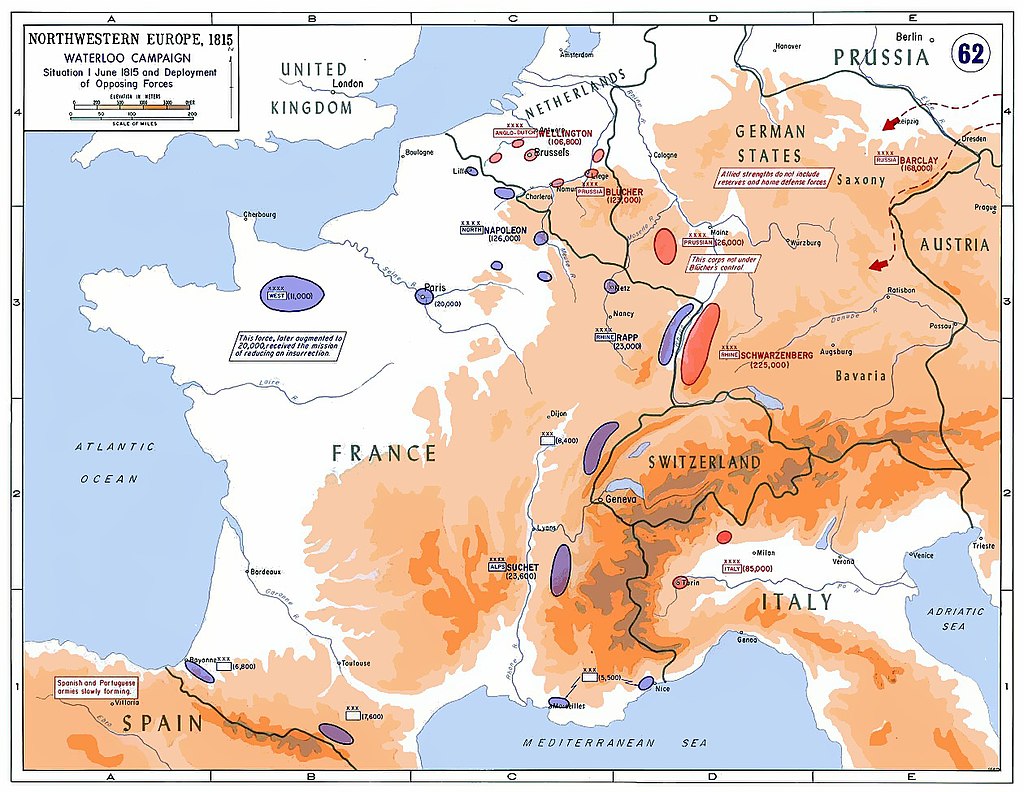

Historian’s Corner: 1814 - The Congress of Vienna

Early in May, 1814, the War of the Sixth Coalition formally came to an end with the Treaty of Paris (not to be confused with the other Treaty of Paris), which restored the Bourbons to France and reset the borders to the 1792 status quo ante. Then the four victorious powers, and Bourbon France represented by Talleyrand, hied themselves to Vienna for the Congress of Vienna - a first. Instead of the 18th century system of cumbersome exchanges of notes between capitals and myriad one on one negotiations around Europe, for the first time all the major stakeholders would be assembled in a single location to hash out what a post-Napoleonic, post-Revolutionary Europe would look like.  For months, the assembled princes and notables of Europe - over 200 states and royal houses in total - met and negotiated (and danced, like, a lot - there were far more balls than actual negotiations. To be fair, a great deal of negotiation probably happened at these informal social events) and redrew the map of Europe. For example, the old Duchy of Warsaw went to Russia, but was forbidden from being united into a greater Kingdom of Poland since this would greatly empower the Tsar. This became known as Congressional Poland and was under Russian rule until 1915. Prussia was compensated with ⅗ of Saxony, which had chosen the wrong side in the last war and waited too long to defect. Other adjustments were made to Austria, Sweden, Denmark, overseas colonies, etc. The goal of the Congress was to prevent another general war like Napoleon had provoked, and to secure the peace of Europe for the future. The five Great Powers (Talleyrand had quickly and skillfully inserted France as an equal in the process) would act in concert to preserve national borders and the status quo. Liberalism and nationalism were to be suppressed as dangerous and destabilizing. The Congressional system thus created would prove the foundation for a period of peace and expansion the likes of which Europe had never known, lasting with greater or smaller incident right up to the assassination of the Austrian heir to the throne in 1914. One of those little incidents rudely interrupted proceedings in March, 1815, when shocking news arrived from France: Napoleon had escaped from Elba, and was marching on Paris! —-  I think Napoleon tried to make a fair go of Elba, he really did. He busied himself improving the small island’s roads and infrastructure and reforming its tiny army, making brigades of mules. However, events quickly conspired against him. King Louis XVIII, for one, absolutely was not going to pay the specified 2 million annual pounds of upkeep specified for Napoleon in the Treaty of Fontainebleau. For another, there was talk in the Congress of relocating Napoleon someplace more remote from Europe, possibly the Azores or St. Helena, to keep him out of trouble. Meanwhile, things looked ripe for him in France. Louis XVIII was another Bourbon mediocrity like his unfortunate uncle, and behind him was an enormous train of emigres eager to slide back into their old positions and privileges, as if the preceding quarter-century had never happened. The soldiers and peasants were deeply suspicious of the restored monarchy, which quickly dissipated its goodwill through ineffectual, unfocused government amidst a time of economic crisis and popular instability. Napoleon had nothing to lose - he was unlikely to be allowed to stay in quiet retirement on Elba in any case - and possibly an empire to gain. So, late in February 1815, he gave his lax watchers - not captors, not yet, not until St. Helena - the slip and sailed for France with 1,000 men in his personal bodyguard. He landed in France, where the local authorities - Marshal Massena, in Marseilles - made no real attempt to apprehend him. Panic spread amongst the Bourbon loyalists and abroad as word got out that the devil was unchained, and Louis dispatched Marshal Ney to arrest his old master. Ney vowed to bring Bonaparte back “in an iron cage.” Outside Grenoble, the first real check appeared, as the 5th Line Regiment confronted the weak band of adventurers. It looked as if real civil war might break out, but Napoleon coolly stood his men down and advanced. The moment was recorded: “Soldiers of the 5th! Don’t you recognize me? Well, if there’s any man here who wants to shoot his Emperor…here I am!” he declared, baring his chest to the leveled muskets of the 5th. With one accord, the soldiers broke ranks and flocked to their old commander, bellowing “Vive l’Empereur! Vive l’Empereur!” Grenoble opened its gates and the citizens gave a feverish welcome. As Napoleon recalled, “Before Grenoble I was an adventurer, after Grenoble I was a ruling prince.” The moment of the 5th’s defection is captured in the 1970 film Waterloo, which is an excellent movie if you’re interested in this stuff: Every army sent by Louis to arrest Napoleon instead defected to the Emperor. His magnetic charisma pulled everyone into his wake. Some wag posted a large noticeboard in Paris: “From Napoleon to Louis XVIII - My good brother, there is no need to send any more troops. I have enough!” Louis could tell well enough which way the wind was blowing and got the hell out of town. Napoleon entered Paris on March 20th. The Hundred Days, as they were later known, officially began. The Emperor immediately put out peace feelers to Vienna, which were immediately rejected. Already in Vienna assembled, the allies pledged themselves to a Seventh Coalition, raising over half a million men, with orders to march on Paris and have a very serious conversation with Napoleon about his mischievous behavior. England and Prussia already had 150,000 men in the field, and Austria and Russia began mobilizing. Napoleon, hesitant to mobilize the French people, still war-weary from 20 years of bloodshed, had no real choice. He had about 200,000 men to meet five times that number in the field, and by June 1 had managed to raise that number to only about 280,000 of uneven quality, with 150,000 more fresh conscripts behind that, to meet a nearly bottomless well of Coalition manpower.  Situation at the start of the Hundred Days. France is badly outnumbered on all fronts. Against that, the Coalition fielded five armies, eventually. The Duke of Wellington was hurried from Vienna and placed in command of an Anglo-Dutch army of about 110,000 at Brussels - his old Peninsular army backed by fresh Dutch conscripts. Blucher with 120,000 Prussians was camped around Namur. Schwarzenberg was placed back in command of an army of over 200,000 Austrians on the upper Danube, who would advance over the Rhine, and 75,000 more were in Italy. Finally, Barclay de Tolly was given 150,000 Russians and would march west as rapidly as he could. Napoleon could either await this converging mass and prepare near Paris to repeat his defensive campaign of 1814 - but with 300,000 instead of 90,000 men, against Allies tired of marching and with great strategic wastage. This way he might hold out long enough to negotiate a ceasefire and retain the throne of France. Or, he could attempt to take the field right away against the nearest allied armies - Wellington and Blucher. He had only 125,000 men against 230,000 Coalition troops, but a sudden victory here might knock England and the Netherlands out of the war, and then leave him free to concentrate solely on the Austrians and Russians. Napoleon resolved to attempt a repeat of his brilliant Italian campaign of 1796: A blow against the ‘hinge’ of the two allied armies near Brussels would drive them apart - the British falling back towards the Netherlands and the sea, the Prussians towards the Rhine. Then he could beat each in detail. By mid-May, Napoleon was on the move north. He intended, once his army was assembled early in June, to strike a sudden blow over the Sambre river and seize the vital lateral road linking Blucher with Wellington before either could react. Civilian traffic was clamped down, the frontier was closed, and the troops moved in utmost secrecy: neither Blucher nor Wellington had any inkling what was afoot until June 15, when Napoleon erupted across the frontier. The Armee du Nord consisted of five corps, the Guard, and reserve cavalry. I Corps and II Corps were assigned to the left wing, under Marshal Ney. III and IV Corps made up the right wing, under newly minted Marshal Grouchy, who you may recall from Friedland, Wagram, or the Russian campaigns. The Guard and VI Corps made up a central reserve. Each wing would engage an enemy army and then the reserve would be thrown against one or the other to decide matters. Early in the morning on June 15, 1815, the army suddenly leaped over the border at their British and Prussian enemies. Three days of marching and fighting would bring them to a small village just south of Brussels - Waterloo.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

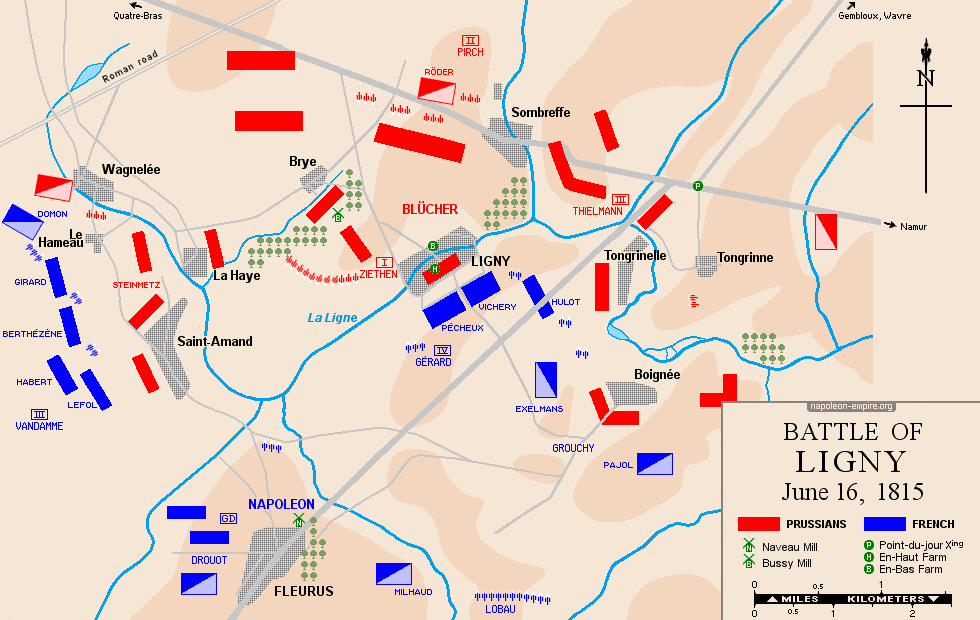

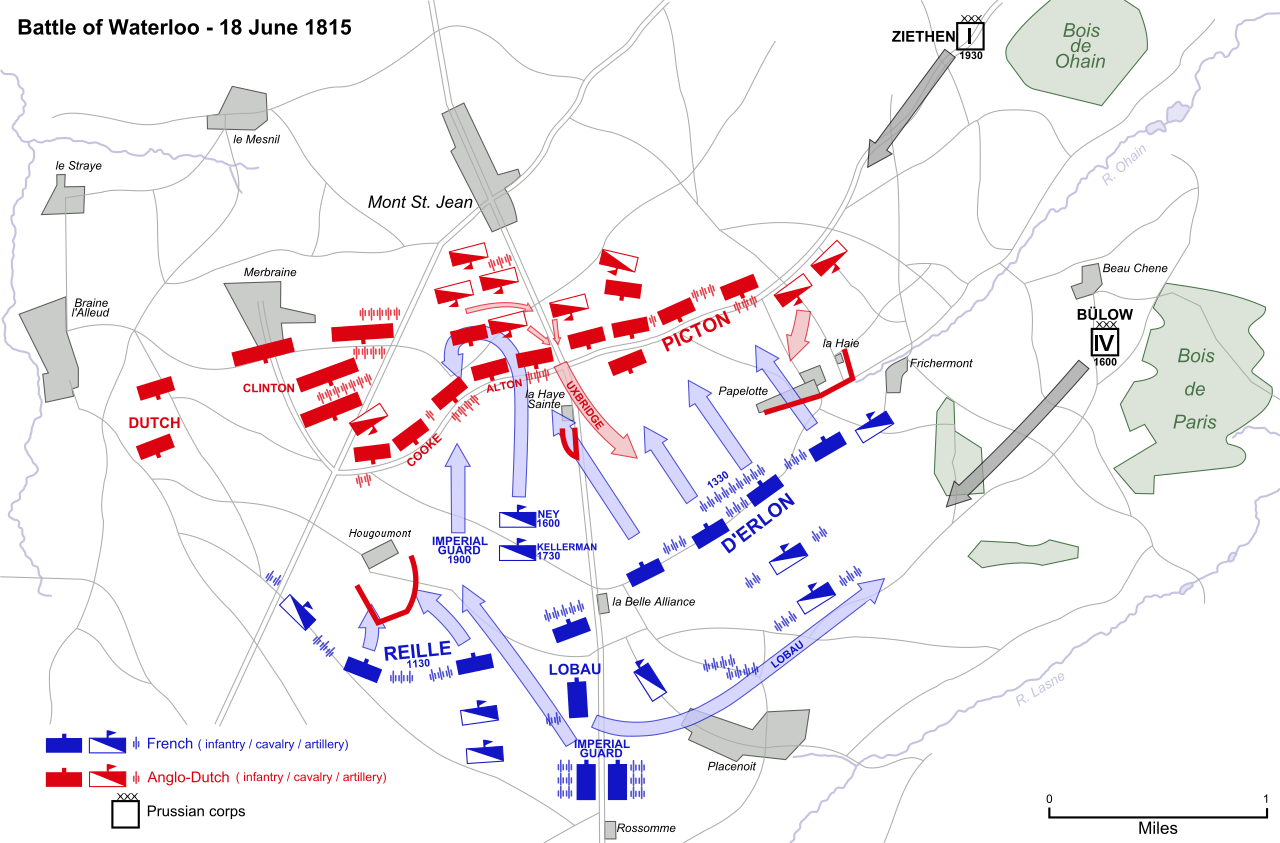

Historian’s Corner: June 1815 - The Waterloo Campaign (I): June 15-16: Ligny