Appreciate the update pace recently.

|

Chevalier Plays AGEOD Let's Play/AAR

|

(February 3rd, 2023, 12:42)sunrise089 Wrote: Appreciate the update pace recently. Thanks. I can play turns during down moments at work and let the game process while busy - I also don't edit the screenshots anymore because people should be familiar with the interface by now, I think, and know where to look on screen (I can go back to editing but it will slow the pace a bit). November -1806 - Emperor's End With the defeat, by and large, of Ottoman field forces I can push the pace in the autumn months a bit - there's not a lot of maneuver going on, just a matter of taking cities, establishing supply depots, and guarding my flanks against the (shrinking) marauding hordes of Ottoman soldiers in the hills. The start of November sees the army of the Habsburgs deeper than they've ever been in Ottoman territory: bearing down on Edirne, the great fortress guarding the approaches to Constantinople.  Mack and Charles link up almost perfectly, forming an army of 100,000 with no real enemy troops between them and the Great City. Apart from Selim's ragged army outside Edirne, the only other Ottoman field army I spot is one guarding the road from Salonika to Constantinople:  I dispatch cavalry to cut his supply lines, and I will move up some task forces on either side to surround and wipe him out, but he's not a priority. On November 4, Charles arrives outside Edirne with his half of the army, and pitches into Selim's forces before Mack can come up. It doesn't matter:  53,000 Austrians against 38,000 Ottomans dug in - but Charles has learned a lot in this war. His experience has pushed his stats to 5-6-7. That means, each turn, Charles rolls a D6 and is active if he rolls a 5 or lower. On the attack, he adds fully 30% to his soldiers' stats, on the defense, he adds 35%. That's the max level possible, meaning Archduke Charles is a match for Napoleon himself (albeit Napoleon has a few more special traits that would give him the edge against the Archduke). Regardless, poor Selim (3-2-2, meaning he is active on a 3 or lower, and adds 10% to values on attack or defense) is thoroughly outgeneraled. 1,500 Austrians fall but the Ottoman army is crushed by Charles' expert generalship, losing 10,000 men and fleeing the field in disorder. Selim pulls west across the Evros River, and there are few Ottoman forces of any size left:  Charles settles into siege lines around Edirne, while Mack's wing of the army comes up, and will push on for Constantinople at the double:  Ottoman morale is clearly collapsing, as a wave of surrenders happens across the front: Edirne, Philippopolis, and Burgas all surrender within days of each other. Every major city between the Danube and Constantinople is now securely in Austrian hands. Everything is looking bright...and then terrible news from Varna shakes the entire Imperial family to its core. There, Kaiser Franz led a small Austrian force forward against Davout's marauders.  There are 30,000 Austrians in the area against only 7,000 French, most of them support staff apart from Honore Reille's guards division, but it doesn't matter. As Franz reconoiters personally near the front, even as Davout beats a hasty retreat, an errant cannonball fired by the rearguard comes near - bounces - and carries away the Emperor's arm. Francis is carried to a nearby peasant house, gravely wounded. Stunned, the army momentarily lets Davout slip the noose, but within a day the pursuit is renewed and Reille is forced to surrender with his ragged band of survivors - barely a regiment strong - at last:  But it doesn't matter. Francis, Emperor of Austria, is dead:

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

December 1806 - The Mother of Cities

Leader death in AGEOD is a random roll of the dice. Division commanders have a fairly modest chance of dying in any engagement, and corps leaders a lower one still. Army commanders are almost never killed in combat. Furthermore, important leaders - Frederick, Napoleon, Lee - will usually simply be "wounded" instead of dying. BUT, across hundreds of battles, sometimes unlucky dice rolls happen. In my first ever campaign as France, I was in the opening month of the decade-long game, executing the Maneuver upon Ulm with the Grande Armee, as historical. Davout's III Corps brushed against some Austrian cavalry patrols, with no losses on either side as the enemy was on passive stance. Davout died. THAT was the most spectacular bad luck I've ever witnessed, and I've played both X-Coms. But this is a close second - an army commander, a head of state no less, dying in a minor brush with a tiny force. Oh, well, sometimes that's how the dice come up. AGEOD seems not to have considered this a possibility, as Francis is still officially head of state:  I shrug it off - the biggest loss is one of my precious few generals - and begin the closing operations of the Ottoman campaign:  No enemy army has come in sight of the great City since Mehmet conquered it 350 years ago, but Mack and Charles will be the first. The long rivalry between the house of Habsburg and the house of Osman has been resolved, decisively, in our favor. Supply lines are excellent, with 2 fully usable routes and a third nearly opened through Macedonia and Greece:  December is quiet, for the most part - Napoleon withdraws towards Budapest for winter, and snow descends on most of Austria and the hilly Balkan areas. Along the supply routes, the surviving Ottoman armies raid and pillage, but mostly are handled by Charles' subordinates. John's army staggers into Sofia for rest and replenishments, detachments storm the capital of Moldova, another Ottoman vassal, and Mack digs siege lines around Constantinople. However, with the harbor wide open, we have no intention of blockading the city - instead we will take the ramparts by storm. The ancient walls of Theodosius are no match for modern cannon:  Charles and Mack each expertly lead their wings, outnumbering the defenders nearly 5:1. There are 270 cannon emplaced along the walls, but they are old, outdated pieces, and the 18,000 Ottoman defenders are poor in morale, discipline, and training. The initial storming parties suffer heavy casualties, but once our grenadiers are in among the defenses the Ottomans quickly crumble. Soon, they are fleeing back through the city streets, and 2 out of every 3 is killed or captured. The victorious Austrians pour into the city, the first Christians here since 1453, and by sunset December 31 Habsburg eagle banners are fluttering atop the Topkapi palace. Constantinople is ours:

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Historian's Corner: 1806 in Reality

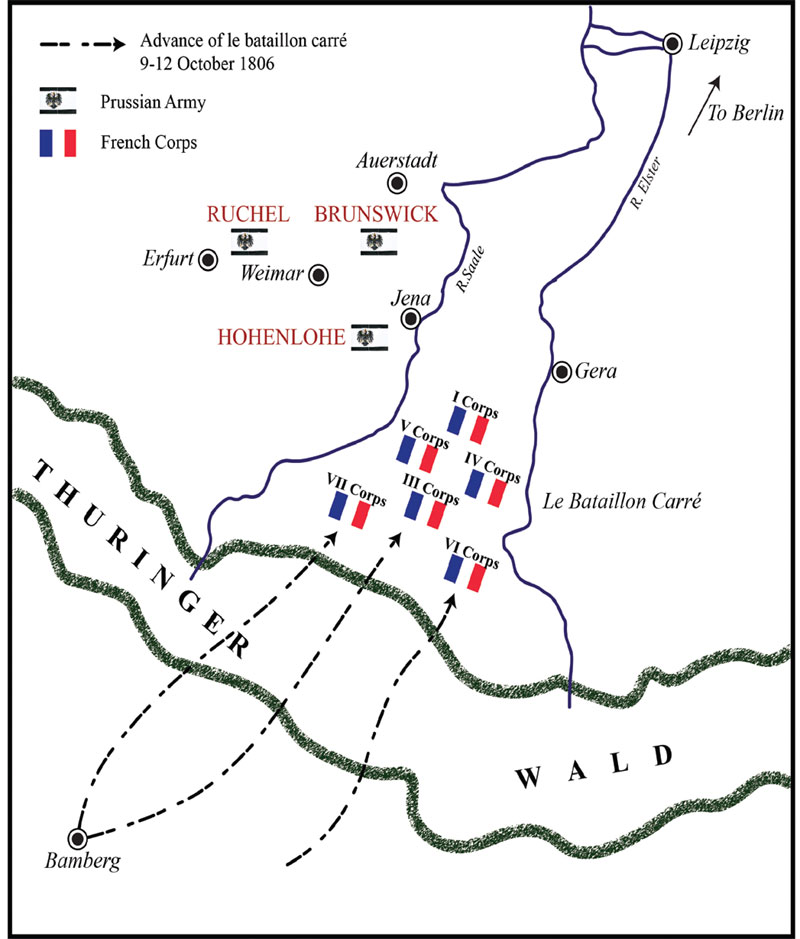

Prussia had been waiting in the wings all through the 1805 campaign. In fact, as Napoleon marched to glory at Austerlitz, there was a Prussian ambassador waiting in Vienna with a declaration of war in his pocket, to be delivered after Napoleon's inevitable defeat and collapse. In the actual event, fulsome congratulations were offered to the Emperor instead (with the address line to the Austrian and Russian emperors hastily crossed out) and Prussia backed down. The real decisive moment of 1805, though, had been the Battle of Trafalgar in late October - the British fleet under Horatio Nelson had completely and permanently smashed the combined Franco-Spanish fleet, ending forever any chance Napoleon had to invade the British isles. For the next decade, wherever there was water enough to float a battleship, Napoleon would find the Royal Navy opposing him. British warships raided and plundered the long coasts of the French Empire at will, British money flowed into the warchests of any and every Continental foe, British weapons armed the armies of anyone opposed to the Ogre of Corsica (in 1812, most of Russia's battalions were equipped with British-made muskets).  Napoleon's empire, 1806 Still, for the moment Napoleon was the master of Europe. Austria surrendered significant lands in the Peace of Pressburg and withdrew inwards to reform and rebuild its armed forces. Russian armies fled as quickly as their feet could carry them into the depths of eastern Europe, Spain was a nominal ally - and Prussia stood alone, unhumbled. Well, not for long, actually - Napoleon had the Black Eagle at his mercy and browbeat Prussia into renouncing all alliances, entering an alliance with France, and surrendering much of its scattered German possessions and closing its ports to Britain, in return for annexing Hanover. By the end of February, 1806, Prussia had cravenly knuckled under and agreed. Napoleon spent much of 1806 attempting to reshape Europe according to French interests - the Army of Italy marched south and subjugated Naples, the German states were reformed into the Confederation of the Rhine (the last remnants of the Holy Roman Empire were swept away), and peace feelers went out to Russia (the Tsar rejected Napoleon's missives and that autumn joined Prussia in coalition). However, Napoleon pushed too far too fast. Patriotic Prussians were outraged at the humiliations, and began lobbying King Frederick William (a weak-willed man without any of his grandfather's force of character) for a declaration of war. When Napoleon, in efforts to make peace with Britain, offered to return Hanover to King George III, the balance in Prussia tipped, and in August the monarchy resolved on war. Napoleon became aware of this in September, 1806, and the two sides raced towards collision. Napoleon's Grande Armee in Germany at this time numbered some 160,000 of the finest, most veteran troops in Europe. Their morale was sky-high, their leadership excellent, their supplies full. With the experience gained in 1805, this was probably the best army Napoleon ever led. Against them, the Prussian army numbered some 254,000, about 170,000 mobile troops with the best reputation in Europe. However, the Prussian army by this point was mostly a paper tiger. It hadn't seriously been tested in combat since the Seven Year's War a half-century before, and it rigidly clung to Frederickian tradition - soldiers ruthlessly drilled to march and fire in line, slow and clumsy to maneuver, tactical initiative discouraged, married to enormous supply trains and frequent magazines - slow, clumsy, and stupid, for all the fine qualities of the infantry. The Prussians had no idea how much the art of war had evolved since Frederick led his men into Saxony - they even still used the same 1754-pattern musket for their infantry, by now the worst in Europe. The high command, in contrast to the youthful French marshals, was ossified and exhausted. The best of the bunch, General Blucher, was a sprightly 64 years old. His superiors ranged from their upper seventies into the low eighties, even. There was no general staff, no corps d'armee system, no less than three official "chiefs of staff" all at odds with one another, vying for power and influence, rudimentary divisions at best - it was a clunky, coughing, sputtering engine of an army, inefficient, slow, and lacking any kind of unified command or theory of war. This, then, was going against the flexible, swift, expertly-led, experienced Grande Armee, which was all directed by the singular genius of Napoleon. It's no wonder that the campaign was a walkover. The Prussians divided their forces into three armies: The main royal army of 70,000 men under the octogenarian Duke of Brunswick concentrated in western Saxony near Leipzig. A second force of 50,000 Prussians and 20,000 Saxons was nearby at Dresden under General Hohenlohe. A final battlegroup of 30,000 was under Blucher and Ruchel in western Germany near Mulhausen - so the Prussians had a slight numerical advantage over the Grande Armee. Chief of Staff Scharnhorst suggested that the Germans should follow a defensive strategy. It was widely assumed, bizarrely, that Napoleon would stand on the defense near the Saale or Main and await attack, as he had done in precisely none of his previous campaigns. Scharnhorst argued that the army should trade space for time, defending along the Elbe or, if necessary, the Oder, until Russian support could come up. Bitter memories of Russian occupation during the Seven Year's War led to the rejection of this strategy - the honor of Prussia, besides, demanded attack. That consideration led to Prussia rejecting a second possible course, concentrating near Erfurt to strike at Napoleon's flanks if he thrust north from his bases in Bavaria towards Berlin. Instead, the Prussians adopted an offensive plan of striking south from Erfurt at Napoleon's communications with the Rhine. The plans for the offensive chaotically divided the army into myriad parts and had them advancing independently in all directions - and by that point the Grande Armee was already on the move.  The Jena campaign begins, October 1806

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Historian's Corner: October, 1806 - The Battle of Jena

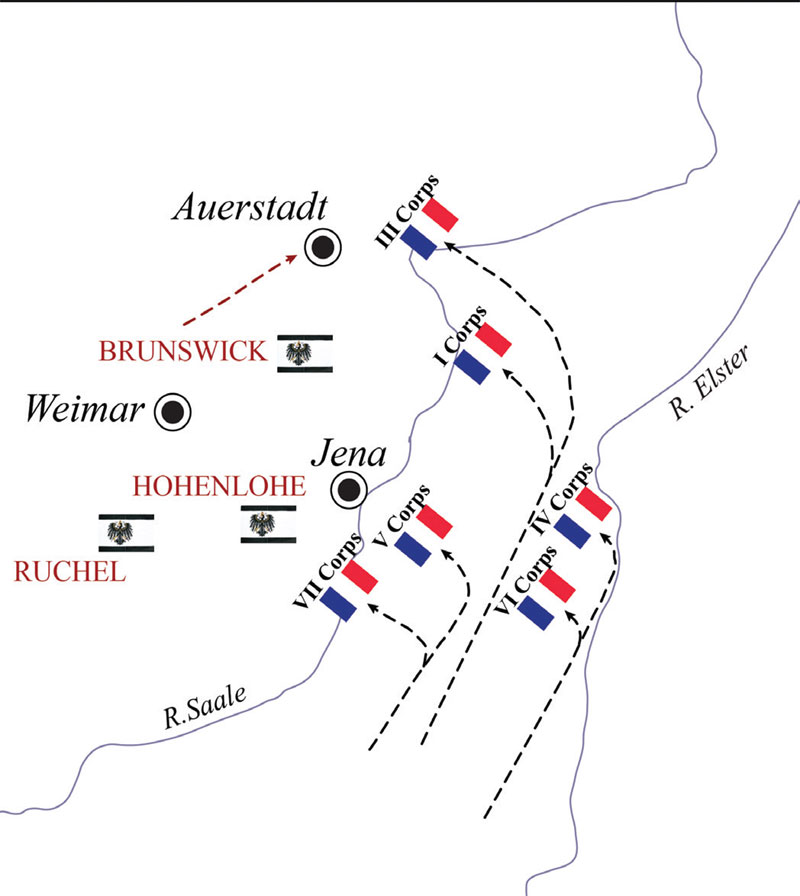

Napoleon was baffled by Prussia's initial deployments in western Saxony, mostly because they were so moronic that he couldn't believe they were true. It was so obviously the correct strategy for Prussia to trade space for time, defend behind the Elbe, and wait for the Russian linkup that anything else seemed to him evidence of a deeper conspiracy than he could divine. By mid-September, though, he accepted that apparently they really were just that stupid, and made his dispositions accordingly. The Grande Armee was encamped in southern Germany, keeping an eye on the Austrians. By the first week in October, the Emperor had shifted his six available corps to just south of the Thuringer Wald, opposite the Prussians in Saxony. The Emperor's goal was to move as rapidly as possible upon the Prussian army, and destroy it before the Russians could arrive to provide aid - much as he did Mack's army at Ulm the previous year. He ruled out a northern approach, via Wesel and Hanover towards Magdeburg (see the Hanoverian front in our Rise of Prussia game) as unsuitable, since the army was encamped in southern Germany and besides, victories along that line would only push the Prussians back towards Berlin - he wanted to destroy them. There was the central route, from Frankfurt-on-Main through the Fulda Gap and on to Berlin - but this way meant crossing difficult, hilly terrain and again driving the Prussian army back towards its base. That left a third possibility, to swing east and then north around the Prussian left flank via Leipzig and Dresden and then on Berlin from the south. The terrain would be tough, with many rivers - including the Elbe itself - to be forced, and thick forests and hills limiting the French to a few good roads. But it offered a secure route to the Prussian rear, with Napoleon's flanks shielded by rivers and his communications safely running along the upper Danube towards the Rhine - out of range of any possible Prussian offensive. It would threaten the Prussian communications, forcing them either to retreat rapidly towards Berlin or else risk being cut off and destroyed, giving ample opportunity for the faster French formations to maul them on the march. If 1805 demonstrated the quality of the French soldier and the depth of Napoleon's brilliance, the 1806 campaign is a triumph of the corps system. Napoleon formed his seven available corps into the "battalion carre," or square battalion. It is worth quoting his orders of October 5 to Marshal Soult, commander of IV Corps, at length:  Quote:I have caused Wurzburg, Forcheim, and Kronach to occupied, armed, and provisioned, and I propose to debouch into Saxony with my whole army in three columns. You are the head of the right column [IV Corps] with Marshal Ney's Corps [VI Corps] half a day's march behind you and 10,000 Bavarians a day's march behind him, making altogether more than 50,000 men. Marshal Bernadotte leads the center, followed by Marshal Davout's corps [III Corps], the greater part of the Reserve Cavalry, and the Guard, making more than 70,000 men. He will march by way of Kronach, Lebenstein, and Schleiz. The Vth Corps is at the head of the left, having behind it Marshal Augereau's Corps [VIII Corps]. This wing will march by way of Coburg, Grafenthal, and Saalfeld, and musters over 40,000 men. The day you reach Hof the remainder of the army will have reached positions on the same alignment. I will march with the center. Basically, the battalion carre or battalion square that Napoleon describes here let the French army move quickly en masse and meet a foe in any direction. Bernadotte's I corps formed the advance guard, with Davout half a day behind and the two wing column's a day's march away. If Bernadotte met a force of 30,00 men or smaller, he and Davout could combine to overwhelm it. If larger, the Marshals would go over to the defensive and Napoleon would maneuver with his other 4 corps on the enemy's flanks and rear. If, however, the enemy fell on Soult's corps on the right, then Soult would become the advance guard as the entire force pivoted in place. Soult and Ney became the advance guard, Bernadotte and Davout became the left flank, the cavalry reserves and Guard with Napoleon became the right wing, and Lannes and Augereau became the reserves. If the enemy hit the left, then Lannes/Augereau became the advance, Bernadotte/Davout the right wing, Napoleon's reserves the left, and Soult/Ney the reserves. Within 24 hours, any enemy meeting a French corps would find himself assailed in front and on both flanks by no less than six - and every single corps was capable of taking care of itself for at minimum 24 hours. Napoleon had no idea where the Prussians were, but his dispositions enabled him to meet a threat from any direction, while he could safely divide his army (!) and march rapidly through the thick Thuringer Wald, a tangled nest of hills and forests separating his troops in Bavaria from the Prussians in Saxony. The Grande Armee surged through the defiles and swiftly began to overwhelm the confused Prussians. The invasion began on October 8 (practically simultaneous with the arrival of an ultimatum the Prussians sent to trump up a war) and by the 10th every corps was through the Wald and surging into Saxony. The Prussian high command was, somehow, surprised by the French suddenly emerging out of the hills on their left flank, and wavered. The Duke of Brunswick ordered a concentration on the river Saale, but some forward Prussian deployments, in consequence of their faulty staff work and clumsy command and control, were left isolated and were steamrollered by Lannes' advancing V corps. The Prussians panicked and began to retreat up the Saale towards Jena. Napoleon assumed the Prussians would retreat towards Leipzig and moved north, expecting to meet the enemy in front of him - but in reality the army of Frederick the Great was much more clumsy than the Emperor anticipated and was sluggishly moving to his north and west, near Jena. No matter - the battalion carre was flexible. On 12 October Napoleon wheeled his forces to the west, Lannes and Augereau becoming the new advance guard and Soult/Ney forming the reserve. Bernadotte and Davout were ordered north and west to take the enemy in the presumed flank and rear.  The wheel to Jena. The Prussians, by now, seriously alarmed by the speed and fluidity of Napoleon's advance, and were thinking only of retreating down the Saale towards Leipzig and the Elbe beyond. Brunswick ordered the main body to retreat north through the village of Auerstedt as rapidly as possible. However, the Emperor believed that the mass of troops Lannes was encountering along the Saale - V Corps had reached Jena the evening of the 12th, and on the 13th had discovered large formations of Prussians on the plain beyond. Napoleon himself reached the city by 4 pm on the 13th, and saw Lannes had seized a bridgehead on the west side of the Saale, estimating he was facing 40,000 - 50,000 Prussians. The Emperor guessed (incorrectly) that this was the main Prussian army and rapidly made plans for a battle. Messengers were sent to summon Augereau (VII corps) by morning (raising his strength to 50,000), by noon he could count on Soult's IV Corps and Ney's VI Corps reinforcing him to 90,000, and finally Bernadotte's I Corps and Davout's III Corps could be approaching from the north. Within the span of 24 hours of having identified the Prussian dispositions, Napoleon could concentrate 150,000 men on the field of battle.  Midnight, October 13 The actual details of the battle of Jena on October 14 don't matter much - you already know a lot about Austerlitz, so the tactics and maneuvers will be familiar, with predictable results as four French corps piled into what turned out to be the Prussian rearguard. Lannes' morning stand on the plateau, Ney too-aggressively blundering his corps into the mass of the Prussian army, the flanking attacks of Soult and Augereau - under the eye of Napoleon himself there was only one way that battle would end. By the time the smoke cleared, the Prussian army at Jena was shattered and fleeing in all directions. But there was a fly in Napoleon's ointment - Davout and Bernadotte had never arrived. When Napoleon found out why, the consequences very nearly resulted in Bernadotte's court martial and execution - and also, bizarrely, altered the fortunes of the Royal House of Sweden. [/i]

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Historian's Corner - the Battle of Auerstadt

Davout's III Corps and Bernadotte's I Corps, initially the advance guard of the army, had become the right wing with Napoleon's wheel upon Jena, and were not present on that battlefield. Napoleon intended them to fall upon the Prussian main body's rear from their positions to the north and east while he attacked from the south, but despite the smashing victory at Jena - 25,000 Prussians had fallen at the cost of just 5,000 Frenchmen - Davout and Bernadotte had never appeared. What had happened? The answer to that was waiting in Napoleon's tent when he retired on the evening of October 14. There, he found a messenger from Davout - the Iron Marshal claimed to have faced down the main Prussian army with his corps of 26,000 men - and furthermore, that he had defeated them! "Your marshal is seeing double," Napoleon snapped, and went to bed. But Davout was not - the Emperor, rather, had miscalculated. The Prussians were falling back as rapidly as they could for Leipzig and beyond, and the main route of retreat took them straight through the village of Auerstadt. Davout, meanwhile, was leading his corps through that village in the opposite direction in an effort to get astride the Prussian rear as ordered - and he ran smack into the onrushing German tide. Thick fog hung over both battlefields, and as Napoleon spent the morning battling at Jena, Davout probed a worrisomely large number of Prussians in front of him. Davout had three divisions - Gudin, Morand, and Friant commanding - and the usual corps support of attached artillery and cavalry, but only Gudin was up early that morning. After initial skirmishing, the Prussians unleashed a powerful attack aimed at shoving the French aside to clear their line of retreat - but the antiquated army was badly coordinated, and the superior quality of the French troops enabled Davout to fend off the attack, if only just.  Prussian cavalry attacks French infantry squares at Auerstadt, October 14, 1806 Interesting to note the squares are oriented corner to corner, not face to face - this helps prevent friendly fire as the men in the square fire outwards. Momentarily recoiling, the Prussians under the elderly Duke of Brunswick paused to bring up another division as reinforcements, and went in again - only Davout had just gotten Friant's division into the field. The Iron Marshal was a tactical master that morning, shifting his reserves this way and that, meeting each clumsy Prussian thrust just in time to turn the blow aside. Still, by 10:00 am, all of his reserves were committed, Morand's division was still three miles away, and Bernadotte - ? Bernadotte was marching away. The genius of the battalion carre system was that each corps was meant to have a neighbor able to reinforce it on the same day in case of trouble. Soult was paired with Ney, Lannes with Augereau, and Davout's buddy was Bernadotte's I Corps. Except Bernadotte had orders from Napoleon to march to the Jena battlefield - orders drawn up when the Emperor thought he was facing the Prussian main body, orders each Marshal was expected to use his own initiative and discretion in following. Bernadotte could hear the cannon thundering away to his north, and Davout was deluging him with calls for aid. But Bernadotte stupidly, stubbornly refused to march north to his fellow marshal's help. It was later speculated that he was jealous of Davout's personal and professioanl success, and didn't mind seeing the Iron Marshal brought down a peg. Bernadotte ignored standing orders that corps were to support each other. Instead, he led his men slowly towards the Jena battlefield - where Napoleon was already overwhelming the outnumbered Prussians. So slow was Bernadotte's march that he arrived at Jena a full three hours after the Prussians had fled the battlefield. I Corps would participate in neither battle that day, stuck uselessly in between.  Situation about 2 pm. At Jena, lower center, the main Grande Armee smashes the Prussian rear guard. To the north, at top center, Davout fights a desperate battle outnumbered 3:1 at Auerstadt. At center, Bernadotte mills uselessly between both battlefields. Davout won his battle with grit, determination, and not a little bit of luck. The elderly Duke of Brunswick fell leading a pair of grenadier regiments forward, and King Frederick William III passively allowed confusion and disorder to spread through the Prussian ranks, neither assuming command himself nor appointing a new commander in chief. Leaderless, the Prussians launched uncoordinated attacks on Davout, who fended off each in turn. By 11, a fresh Prussian division under the Prince of Orange came up. The Prince split his forces in two, sending one brigade to each flank - and ran smack into General Morand, who intervened now decisively in the battle. Morand flung his entire division onto the French left flank and shattered the Prussian assault, then rolled up the army. The Prussians - still vastly superior in numbers - were uncoordinated and outmaneuvered as the French now formed a crescent around the bulging mass and drove them to the rear. By 12:30, Frederick William bestirred himself to order a withdrawal, hoping to rejoin the troops left at Jena who were hopefully still intact (they were not). The French instantly pursued, and the Prussian army dissolved into panicked flight. Davout pursued until sunset. He inflicted 13,000 casualties in return for 7,000 losses of his own. Napoleon heaped praises on Davout when the full picture became known to him. III Corps had taken on and beaten in open combat virtually the entire Prussian army - 65,000 men against 26,000. Davout was made Duke of Auerstadt and his corps led the victory parade into Berlin two weeks later. For Bernadotte, though, the Emperor had only scorn. Quote:According to a very precise order, you ought to have been at Dornburg...on the same day that Marshal Lannes was at Jena and Davout reached Naumburg. In case you had failed to execute these orders, I informed you during the night that if you were still at Naumburg when this order arrived you should march with Marshal Davout and support him. You were at Naumburg when this order arrived; it was communicated to you; this notwithstanding, you preferred to execute a false march in order to make for Dornburg, and in consequence you took no part in the battle and Marshal Davout bore the principal efforts of the enemy's army. The army was outraged at Bernadotte, who only narrowly escaped a court-martial thanks to his familial connections with Napoleon, and from then on the Marshal of I Corp's star was in eclipse. The Prussian Army, meanwhile, was shattered - all three field armies had been brought to battle and defeated by Napoleon in the course of a single day. The rearguard overwhelmed at Jena, the flight of the main body interrupted and broken up by III Corps, virtually all order dissolved as the Prussians fled to the north and west - away from Berlin and ruthlessly pursued by the French. Half a century before Jena & Auerstedt, Prussia and her army had stood for seven years against the combined powers of Russia, Sweden, Austria, and France. Now, Napoleon destroyed her army in a single morning and overran the kingdom in 33 days. The army, briefly concentrated for battle, now dispersed into half-a-dozen separate detachments, harrying and closely pressing the retreating Prussians. One by one detachments were cornered, brought to bay, surrounded, and forced into surrender. Murat took 14,000 prisoners by the 16th, added to the 25,000 already in French hands after the battles on the 14th. Bernadotte hit the Prussian reserve at Halle on the 17th, losing 800 men to inflict 5,000 more losses on the Prussians. By the 20th, the French were on the Elbe all along its length. Blucher was fleeing with his forces through Brunswick, the Prussian reserves were trying to rally at Magdeburg, and Hohenlohe - in command now that Brunswick was dead - was fleeing for the Oder. By the 22nd, the French were over the Elbe in force, and by the 24th - after a pause to pay tribute at the tomb of Frederick the Great - they were in Berlin. After a pause for a few days to review and organize the occupation of the city, the Grande Armee sped onward, towards Stettin-on-the-Oder, where Hohenlohe was trying to rally the survivors. Bernadotte, Lannes, and Murat's cavalry came up hard on him at Prenzlau, where the three marshals bluffed him into surrendering his entire command. 14,000 more Prussians went into the bag, followed by the city of Stettin itself and another 5,000 soldiers on October 29th. ![[Image: 1280px-Charles_Meynier_-_Entr%C3%A9e_de_...e_1806.jpg]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/de/Charles_Meynier_-_Entr%C3%A9e_de_Napol%C3%A9on_%C3%A0_Berlin._27_octobre_1806.jpg/1280px-Charles_Meynier_-_Entr%C3%A9e_de_Napol%C3%A9on_%C3%A0_Berlin._27_octobre_1806.jpg) By October 30th, then, a bare two weeks after the battle, the only remaining Prussians in the field were Blucher's command, attempting to break across the north German plain towards the Russians advancing through Poland. Blucher had rallied 22,000 to his side, but found himself cut off at every turn, and gradually he was cornered at the Baltic port of Lubeck on November 5 where he hoped to take ship for England with his corps. The French were in town practically on his heels, however, and Blucher, too, was forced to surrender. A single month had sufficed to exterminate the Prussian military. 25,000 killed and wounded and 140,000 soldiers made prisoner - virtually the entire pre-war military. However, the war was not finished. Once again, the legions of Holy Russia were drawing near from their bases in the depths of eastern Europe, and Frederick William and his fiery wife Louisa had fled to their ancestral home in Konigsberg, East Prussia. As 1806 drew to a close, Napoleon was faced with a difficult winter campaign in Polish blizzards against the stoutest warriors in Europe. It would be his stiffest challenge yet.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Sorry for the pause, everyone. THe last few weeks have left me no time to play or to write.

Furthermore, diplomacy in Wars of Napoleon ahs proven extremely frustrating. The interface is totally opaque, the AI is unreasonable, and the demands not at all related to your goals or strategic desires. For example, I can't demand Bucharest since it's part of Wallachia, but can't negotiate with Wallachia since they're Ottoman vassals. I can't demand Sarajevo for reasons unknown to me, and the random territories I CAN demand get rejected by hte Ottoman AI anyway, despite their 0 National Morale since the fall of Constantinople and my 200 points of warscore, which has seeming no relation to the peace table. Basically, I can't make peace by asking for what I want, I don't know why I can't ask for what I want, I don't know why the AI won't agree to anything anyway, and this all has to be done on multi-turn cycles since the way the game handles diplomacy is (send offer) -> end turn -> AI considers -> end turn -> AI replies -> end turn -> I can make a new offer. Give me Paradox diplomacy any day! I'd even take Total War at this point! (This is only an issue in Wars of Napoleon - obviously it doesn't matter in 2-player games, like most of AGEOD, and it doesn't really matter as France since as the Protagonist Nation you can use scripted events anyway). Anyway, I've played through March with no major battles, just chasing Ottoman bandits in the Balkan hills, while the Porte refuses to make peace and I regroup my armies. Not sure where to go from here.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Historian's Corner - The Winter Campaign of 1806 - 1807

Quote:In our history, early 1807 was largely quiet, as Austria has largely completed the conquest of the Balkans, while the phony war between France and Austria continues and the rest of Europe continues in neutrality. Little events of note happened between the fall of Constantinople at the end of December, 1806, and the opening of the spring campaign season in April, 1807. Although Napoleon's destruction of the Prussian army in the maelstrom of a single day's battle at Jena and Auerstadt astonished all of Europe, the war of the Fourth Coalition dragged on. King Frederick William fled to his ancestral holdings in Konigsburg, far to the east, and vowed continued resistance, supported by Tsar Alexander. Austria stirred ominously to the south, though the Schonnbrunn didn't dare risk open war quite yet, and of course English gold continued to pour into the coffers of anyone who looked at Napoleon sideways, or even looked like they MIGHT look at him sideways. From Berlin in November, 1806, Napoleon issued a series of decrees that sowed the seeds of his ruin: unable to strike at England directly following the destruction of his fleet at Trafalgar the previous year, he attempted to cow the island economically, proclaiming all English trade with the Continent under blockade, establishing the Continental System. While it was totally ineffective at strangling English trade (and provoked a far more effective English blockade of French goods in response), the Berlin Decrees further led Napoleon astray into wars with Russia, with Spain, and, most disastrously of all, with an invasion of Russia itself in 1812 in efforts to compel all Europe to adopt his economics by force. For now, we'll concern ourselves with Napoleon's second clash with the Russians, in Poland during the winter of 1807. Faced with Prussian intransigence and rumors of Russian armies advancing into Poland, Napoleon resolved that the best place to meet them was not on the Oder, but on the Vistula. III Corps, V Corps, VII Corps, and the newly forming IX Corps under Jerome Bonaparte would move out for Thorn and Warsaw, along the Vistula. A second wave of VI Corps, I Corps, IV Corps, and the cavalry reserve would follow once they finished the Prussian mop up operations still ongoing. He would strike a political blow in the process - stripping Prussia of the Polish conquests it had made in the last thirty years by creating the "Duchy of Warsaw" would punish the Hohenzollern monarchy and serve notice to the Tsar and Emperor of Austria that the same could be done with their own Polish acquisitions. By the end of November, the Polish capital and the great fortress of Thorn were both in French hands, while the Russian advance corps and a few Prussian remnants withdrew to the eastern bank of the Vistula. The army Napoleon was concentrating along the river was, typically, massive. Fresh conscripts from the classes of 1806 and an early callup from the class of 1807 largely made good the losses in the Prussian campaign, and Napoleon disposed of 172,000 infantry and 36,000 cavalry in the Grande Armee. Holland and Spain supplied 35,000 more auxiliaries. So, in numbers, the army of France was as strong as it ever was - but its razor sharp edge was beginning to dull a little. The long months of campaigning from the Main in September to the Vistula in December had wearied the men, and morale was sinking. Poland, bluntly, sucked (quite literlaly, too, in the winter muds). It was poor, it was cold, far from the lights of Paris and the comforts of home, and there were murderous Cossacks constantly prowling about. Facing them, the Russians fielded 49,000 infantry and 11,000 cavalry under General Bennigsen, leading their most advanced battlegroup. A second force under Marshal Buxhowden of 39,000 infantry and 7,000 horse was nearby. Both armies answered to veteran Kamenskoi, who could thus oppose the French with about 100,000. The remainder of the Russian armies were in St. Petersburg, facing the Turks in Moldova, or in reserve in Russia. The infantrymen were hardy and brave, but poorly armed, barely paid, and badly led. Russian cavalry was as good as the French, the irregular Cossacks the best light cavalry in Europe, and the artillery was both numerous and high in quality. The raw material, though, was hampered by abysmal administration, hopeless supply services, and useless high command. Bennigsen was mediocre, Buxhowden had fought (badly) at Austerlitz you may recall, and the two men hated each other. Kamenskoi was ancient, and the two men of quality, Barclay de Tolly and Prince Bagratian, too young and junior to exert much influence. Situation late December, 1806 In late December, Napoleon lunged from Warsaw north of the Vistula in an effort to snap up the nearby Russian corps, and a series of confused but indecisive battles erupted along the rivers Bug and Narew as the Russians skedaddled north as quickly as their legs would carry them. The thick winter mud and snows hampered French pursuit, and after losing much of his army to straggling and marauding, the Emperor decided to go over to winter quarters for a few months while he got up more supplies, incorporated his replacements, and rested and replenished for the spring campaign. The French line at this time extended from Elbing on the lower Vistula along the river to Warsaw, facing the Russians and Prussian remnants encamped to the northeast. Napoleon busied himself with diplomatic intrigues, attempting to bring Persia and Turkey into the war with Russia, and other diplomatic intrigues, taking a Polish countess as a mistress (to Josephine's rage). Late in January, 1807, the Russians suddenly lunged forward. It seems that Ney had led VI Corps north from its winter quarters into the East Prussian lake area around Allenstein (the scene of so much grief between Germans and Russians in 1914, and again in 1944), sweeping the area for food and other supplies. Bennigsen had attempted to take advantage of the French disorganization on the left and had begun a surprise winter offensive in northern Poland (ugh), hoping to reach the Vistula and position himself to cut Napoleon's supplies towards the Oder in the spring. Bernadotte's I Corps, on the far left of the army, bore the initial brunt, and the Marshal (still under a cloud due to his abysmal performance at Jena), reacted quickly, concentrating his corps and sending word to Napoleon. The Emperor was quick to perceive the flaw in Bennigsen's plan: a deep Russian thrust to the west, across the face of the French along the Vistula, would badly expose their own left and open the way for him to fall upon the Russian communications. Bernadotte was ordered to lure the Russians further westwards, while III Corps, IV Corps, V Corps, and VII Corps would spring north from the area of Warsaw towards Allenstein, Ney's VI Corps maintaining contact between the two wings of hte French army. Lefebre's new X Corps, forming that winter for the siege of Danzig, was instructed to fall back to Thorn to backup Bernadotte. Napoleon wrote to Murat: Quote:The staff will have sent you your movement order. I plan to open the offensive on the 1st February, although on that day the army will only make a short march. Napoleon emphasized secrecy and speed, with the hopes of catching Bennigsen flat footed, piercing his center at Allenstein, and driving the Russians back in two halves in opposite directions, whence he would be able to deal with both at leisure. In a twist of fate similar to the Antietam campaign in Maryland, 1862, a copy of Napoleon's orders was lost along with its courier, when the young officer was snapped up by Cossacks on his way to join his unit in the unfamiliar Polish countryside. By February 1 Bennigsen knew Napoleon's full plan and was in total retreat. Poor Bernadotte, meanwhile, received no word from Napoleon until February 3, as fully 8 couriers counting the first were all captured by Cossacks. The hapless Marshal was accordingly once again too late for the great battle of the campaign. Unaware that Bennigsen was already rapidly concentrating in front of him, Napoleon proceeded with his plan - but to his dismay found no Russians in front of him as his blow landed on empty air. Puzzled and uncertain of the Russian whereabouts (the Cossacks kept Murat's cavalry safely at bay), Napoleon groped forward with his corps, deciding that the enemy was probably retreating but hoping to catch him in the open before he made good his escape. A few miles north of Allenstein, Napoleon caught part of the Russians at Ionkovo (or Jonkovo), pitching into them with his Guards division and five infantry divisions from Ney and Soult - but the short winter day robbed the French attack of much of its force, night falling before they could really get to grips with the Russians, who slipped away during the hours of darkness. Bennigsen had, just barely, escaped from the jaws of Napoleon's trap thanks to his early warning from the Cossacks. Disappointed, Napoleon nevertheless issued a victory bulletin, and hurried his columns in pursuit of the fleeing Russians, hoping to catch them and deal them one last good blow before the Winter Campaign came to a close. Just down the road was the village of Eylau. Next time: "Quelle massacre! Et sans resultat!" - The Battle of Eylau

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Historian's Corner - Winter, 1807

Winter War: The Battle of Eylau None of the great Napoleonic battles is surrounded with more doubt, more uncertainty, than the battle of Eylau. The thick blizzards and blinding gunsmoke that obscured the battle on the days of gave way to even thicker clouds of propaganda, mythmaking, and obfuscation after the fact. What everyone can agree on is that, like Frederick's two great battles against the Russians at Zorndorf (1758) and Kunursdorf (1759), it was a holocaust, fought under the worst of weather conditions. Authorities agree on little else - but I will try, following David Chandler, to give an outline of the furious struggle that developed around this little East Prussian village in the snowy February of 1807. Fleeing north from his narrow escape at Ionkovo, Bennigsen turned at bay on the evening of February 6th. He needed to buy time for his slower guns to make their escape, intending to fight a rearguard action against Napoleon. The first French began to straggle in at about 1400 the next day, February 7th. The Emperor had allowed his corps to spread out considerably in the days following Ionkovo, and he only had Soult and Murat immediately available, with Augereau and the Guard joining later in the afternoon, about 45,000 all told against the 67,000 Russians Bennigsen already had concentrated. Ney and Davout, with 15,000 each, were less than a day's march away, while Bennigsen was hoping for the arrival of a small Prussian task force under one General L'Estocq, about 9,000 strong. Bennigsen considerably outgunned the French, 460 tubes to 200. ![[Image: Battle_of_Preussisch_Eylau_Map1.jpg]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8d/Battle_of_Preussisch_Eylau_Map1.jpg) The French arrive on the plateau in front of Eylau, February 7 1807 All these things militated against launching an attack on the Russians that afternoon, and one of the areas of fog in the battle revolves around whether Napoleon ever intended to attack Bennigsen that day. To be sure, some 'official French sources' claim that Napoleon deliberately launched a pinning attack on Bennigsen beyond the village, with a view towards seizing shelter for his men for the night in the wintry weather, and to preventing yet another Russian escape. This view is contradicted by many contemporary sources, who instead assert that Murat and Soult's blunders brought on an engagement before Ney and Davout could come up and Bernadotte could draw nearer. A young captain in Augereau's corps overheard the Emperor say to the Marshal, "Some of them want me to storm Eylau this evening; but I do not like night fighting, and besides, I do not wish to push my center too forward before Davout has come up with the right wing and Ney with the left; consequently I shall await them until tomorrow on this high ground, which can be defended by artillery, and offers an excellent position for our infantry; when Ney and Davout are in line, we can march simultaneously on the enemy." Regardless of Napoleon's wishes, whether it was troops foraging for shelter, a deliberate assault by Soult, or a blundering detachment of the Emperor's baggage train (I've heard all three), a sharp skirmish erupted in the valley below Napoleon's position on a plateau overlooking Bennigsen's army, as French troops attempted to eject the Russians garrisoning the village. Both sides fed in reinforcements and what began as an outpost skirmish escalated into a furious battle for possession of the hamlet's warm houses and sturdy church. The battle raged from shortly after 1400 until 2200, when at last the weary and beaten Russians slunk off to the ridges north and east of town. Both sides lost about 4,000 men in the struggle, including General Barclay de Tolly on the Russian side (wounded in the arm) and French general of division Lochet. ![[Image: 1920px-Battle_of_Eylau_1807_-_attack_of_...3%A9on.jpg]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/Battle_of_Eylau_1807_-_attack_of_the_cemetery%2C_by_Jean-Antoine-Sim%C3%A9on.jpg/1920px-Battle_of_Eylau_1807_-_attack_of_the_cemetery%2C_by_Jean-Antoine-Sim%C3%A9on.jpg) The struggle for Eylau, February 7, 1807 The night was miserable. The thermometer plunged to 30 degrees of frost, and the majority of both armies huddled in the open. The Russians went without food, due to their habitual disorganization, and the French also went hungry, due to the breakdown of the long supply lines stretching from East Prussia to France. It was one of the worst nights any of the grognards had experienced - but the day to come would be worse. The 8th came with continuing, blowing snowstorms, wiping out visibility and rendering the two armies like men fistfighting in a pitch-dark room. Eventually, the French were able to pick out the Russian positions on the ridges east of Eylau, and Napoleon, though still outnumbered without two of his corps, opted to launch a pinning attack with Soult until Davout could come up on the flank. Augereau and Murat would then be committed against the center, while Ney would come up on the left and cut the retreat towards Konigsberg, while the Guard was in reserve. If all went well, the Russians would find both their flanks enveloped and their center broken - the army could be annihilated. However, in a critical oversight, Ney, who was supposed to be shadowing L'Estocq's Prussians, had not been sent updated marching orders the night before - and received no word from the Emperor all morning. VI Corps would not arrive before nightfall. ![[Image: NapWars73.jpg]](https://www.westpoint.edu/sites/default/files/inline-images/academics/academic_departments/history/Napoleonic%20wars/NapWars73.jpg) Situation early 8 February, 1807 The ball opened on the 8th when the Russians began a bombardment of the village of Eylau, rudely turning the French troops out of their warm billets into the blowing snowstorms. The Grande Armee's artillery was not slow in replying, and soon a furious cannonade was flying back and forth across the valley. Soon the village was blazing, and a thick pillar of black smoke rose towards the horizon, adding to the general gloom of the day. Napoleon threw forward his left divisions in a demonstration, hoping to distract Bennigsen from Davout approaching from the south. Tutchkov, commanding the Russian right, organized a furious attack, driving Soult back upon Eylau, while at the same time the mass of Russian horse began to fall upon Friant's division, leading III Corps. Soon both French flanks were actually in jeopardy. Faced with the unpalatable option of attempting to disengage and withdraw to buy time for VI Corps and the rest of III Corps to arrive, or to win that time by attacking, Napoleon wasted little time before ordering Augereau forward, supported by St. Hilaire's division from Soult's corps. Augereau, though he was ill and had to be helped on his horse, did not hesitate a moment to lead VII Corps forward. The driving blizzard now reached its height, and Augereau's men soon lost all sense of direction in the whiteout. Blundering forward, they stumbled right into the center of Russian lines, where the surprised Bennigsen had 70 guns in battery massed. The guns belched canister, shredding VII Corps, and the blinded French artillery, attempting to fire in support, fratricidally fired into the mass as well, unable to correct their aim in the snow. St. Hilaire's division, alone reaching the objective, was easily driven back, and VII Corps almost ceased to exist as an organized formation. By 10:30 am, then, a gaping hole yawned in the French center even as both flanks were being driven into retreat. General Doctorov led Russian infantry reserves forward against Augereau's dissolving command, while the ailing Marshal rallied his survivors - only two or three thousand men out of the ten thousand who had gone forward that morning - in the churchyard at Eylau. The 14th Regiment of Line was cut off in no man's land beyond the village, formed square, and went down fighting to a man. Five or six thousand more green-clad infantry swept around VII Corp's survivors and stormed Eylau itself. Napoleon's own person came in danger at his command post in a church steeple, only the courage of his personal escort holding the Russians off long enough for the Guard to come pounding up and drive the Russians off. Both his flanks reeling backwards, his center collapsing, Napoleon turned to hte last expedient he had: Murat's 10,000 cavalry reserve. He ordered the dashing Grand Duke of Berg to send his men into the breach and save the army. What ensued was one of the most famous incidents of the Napoleonic Wars. ![[Image: 1280px-Battle_of_Eylau_1807_by_Jean-Anto...3%A9on.jpg]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9c/Battle_of_Eylau_1807_by_Jean-Antoine-Sim%C3%A9on.jpg/1280px-Battle_of_Eylau_1807_by_Jean-Antoine-Sim%C3%A9on.jpg) The great cavalry charge at Eylau, February 8, 1807 Everyone who knows anything about the Battle of Eylau knows about Murat's great cavalry charge. 10,000 horsemen en masse swept down on the Russian center. Rank upon rank they came on. First Dahlmann and his chasseurs, then Murat himself, in turn the troopers of Grouchy, d'Hautpol, Klein, Milhaud - the largest cavalry charge of the Napoleonic wars, probably the largest in history. Half of Murat's command fell upon the Russians driving St. Hilaire back, scattering those cavalry and saving the division. Half sabered their way through the Russians beleaguring VII Corp's survivors, riding back over the square of dead men, the scene of the 14th's last stand. They crashed through the Russian center, regrouping into a single column behind Bennigsen's army, and then stormed back through, slashing at the gunners who had mutilated Augereau. As the Russians tried to rally and reform in front of Murat, the Guard cavalry came down on them from the other direction, unleashed by Napoleon to win Murat back to safety. At the cost of 1,500 casualties, the Grand Duke of Berg had won time for Napoleon - time enough to save his army. Forever after, the cavalry of the Grande Armee would carry the glory of Eylau with it. Murat would ride the victory clear to his own kingdom (and, ultimately, a firing squad). The crisis of the day was now past, but the battle was not yet over. It was now about 1300, and Davout had gotten III Corps fully deployed on the French right. Now the Iron Marshal led his men forward, linking up with St. Hilaire and sweeping around the open Russian flank. Murat, Augereau, and Soult wearily attempted to hold their positions on the left and center while Davout won the day for France. The sun wore down through the afternoon, towards those early winter sunsets, and all afteroon Davout steadily drove the Russian back - Bennigsen bent, and bent, and bent, and soon the Russian line was almost doubled over into a U shape by III Corp's pressure. ![[Image: Map_of_the_Battle_of_Eylau_-_Situation_a...y_1807.jpg]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/47/Map_of_the_Battle_of_Eylau_-_Situation_about_1600%2C_8_February_1807.jpg) Situation at Eylau, about 1600, 8 February 1807 Now fate intervened to give Bennigsen his own miracle. With his line at the brink of snapping, suddenly men on his right flank saw bluecoated troopers approaching the field. At the very nick of time - L'Estocq's Prussians had arrived (not the last time the Prussians would save the day against Napoleon). The Prussian general had eluded Ney, his pursuer, and rushed to the field at Eylau, while the VI Corps commander had only received Napoleon's summons at 1400 that afternoon. By hard marching and skillful rearguard actions, the Prussians had shaken Ney, come up behind Bennigsen's right, and now passed completely behind the Russian army to intervene on the buckling left. The 9,000 men, in good order and with morale high, swept up hordes of Russian stragglers in their wake, and soon a huge mass of soldiers descended on Davout's weary men. Prince Bagration rallied still more men and flung htem into a general counterattack, and new determination flooded into Russian breasts. Step by step, III Corps was forced to relinquish the ground they had won, and once again the fortunes of war were swinging back in favor of Russia. Napoleon strained his eyes to the north for signs of Ney, the last man who could retrieve French fortunes. It was not until 1900, deep in the twilight, that VI Corps' first soldiers began to file onto the bloody field at Eylau. Ney had been seriously hampered by L'Estocq's rear guard, but now he made a belated but no less welcome arrival. He linked up with Soult on the left and stormed forward into Russian positions, and now in their turn the Russians were forced to halt their counterattack and stem the French attack. By 2200, in full darkness, a weary, stunned stalemate had fallen over the battlefield. Fourteen hours of furious fighting had done little but strew tens of thousands of dead and wounded, the pride of their nations' respective armies, over the little valley of Eylau. An hour later, Bennigsen, convening his top commanders at a council of war, decided to resume his retreat. It was not until 3 in the morning that Soult's outposts, shivering in the frozen night, noticed the Russians slipping out of their lines and moving to the rear. So ended the gruesome battle of Eylau. The French had lost somewhere between 15,000 and 25,000 men (Napoleon claimed 7500 losses, giving rise to the phrase "to lie like a bulletin"), the Russians about the same. It was one of the bloodiest battles since the Seven Year's War half a century before. The French were masters of the field, again, and Bennigsen's winter offensive had been driven back, but it was hardly a victory on the scale of Austerlitz or Jena. Napoleon settled back into his winter quarters, Bennigsen into his, and both armies licked their wounds and girded for the spring campaign. Riding over the field the next day, February 9th, Ney got his first good look at the ground the Grande Armee had struggled over, an army which his late arrival had saved. Looking at the vast fields of corpses, the Marshal famously exclaimed, "What a massacre! And with no result!"

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Spring 1807 Turns: January - July 1, 1807

For us, the spring of 1807 continues to be quiet, with a few clashes of note. Our general plan at the moment is regrouping from the Ottoman War - which drags on at the peace table as the Porte refuses to reasonably negotiate, while preparing a counteroffensive to liberate Hungary at least and possibly Austria itself from French occupation. Most military action is confined to clashes with roving bands of Ottoman marauders up and down the Balkans and a minor offensive into Greece to try and bring the Sultan to the negotiating table.  I am gathering Archduke Charles' army, split into two corps (the maximum I can field) at Belgrade. I have something like 14 divisions total in the army, totaling nearly 150,000 men (will have an updated OoB soon with accurate strength returns). Mack's army is also there, but has no supporting corps, with something like 6 divisions. Charles' army will move north on Pest, keeping the river between us and the major French formations. Recapturing Pest will enable most of Hungary to fall into my lap, which I will sweep up with a detached division under John or possibly Mack's army, which will constitute my major reserve for the campaign.  If Hungary can be regained, our more ambitious goal is to cross the Danube at Buda and move up the right bank of the river towards Vienna, with the goal of liberating the capital. In turn, if successful, we can think about sending a major force into Bohemia to regain Prague, which will largely restore Austrian territory with the exception of Trieste. My reasons for optimism is the high Austrian national morale, about 18 points higher than the French, and the modern structure of Charles' army with a full roster of divisions and a supporting corps. If Napoleon has spread out his forces, as I suspect he has, that will enable me to beat the French forces in detail. Supply won't be an issue since we'll be moving into friendly territory. Objectives as of the end of March, when I made this plan:  France has about 2.5x my military power, which is a hefty disparity. BUT Charles is a match for any French Marshal, Napoleon is, uh, up to some weird stuff -  The Emperor leading an army of pontooniers, medical personnel, and supply trains against the main Austrian army - and I think I can beat them in detail, then use Charles and Werneck's corps to fend off counterattacks. Perhaps by 1808 I can contemplate a counteroffensive into Italy or even Bavaria, in the most optimistic scenario. Otherwise I have little to report from the first six months of 1807. There are about two or three Ottoman armies, about 10,000 strong each, the remainder are in the Caucasus battling the Russians. They raid Edirne, or Kavala, or Tirana, but by and large are pushed around by my garrison forces. My main goal here is to maintain my gains, since I BELIEVE I gain conscripts, money, and war supplies from occupied territory, and certainly produce supplies, but I'm not 100% certain on the economics. The Ottomans refuse to part iwth territory, still, so the war drags on to no purpose, but it's not costing me much at the moment. If I can't demand Sarajevo, Belgrade, and Bucharest at the peace table, I'll occupy the damned places for 8 years if I have to. The campaign is set to kick off from Belgrade on June 1, where Napoleon has assembled a considerable force across the Sava:  Screenshot a few weeks out of date - main change is Mack marching upriver to Sabacz. Facing the Emperor, I have Charles and Wernecke leading their two corps, while Mack is upriver at Sabacz fortress. John and Josef each lead a small force in reserve, albeit not part of the formal army order of battle. My intention here is to cross the river with Mack towards Pieterwarden, in Napoleon's rear. At the same time, Charles will lead a frontal assault, with vastly superior numbers and roughly equivalent leadership (he has gotten GOOD at his trade in the Ottoman war). If all goes well, I can break Molitor's corps under Napoleon, while Mack cuts the retreat at Pieterwarden and I bag the lot, though I expect Napoleon to make good his escape. Crossing the river is a risk, but this is as favorable a chance to defeat the French in detail as I can expect, so I will take that risk. If I fail, I have the fort of Belgrade and the river to shield me as I recover. But it misfires - Napoleon pulls back to Pieterwarden before I can kick off the offensive, as I was waiting for Wernecke's corps to recover from its march all the way from Sofia. That means Mack would be attacking with no support across a river, into a fortified Napoleon. Not going to happen, so I cancel the operation.  Instead, Mack will march back down river to Belgrade to cover the fortress there and serve as my base of maneuver. Charles and Wernecke will cross the Danube and march north, swinging beyond Napoleon's left towards Pest, which is about 2 weeks away. We can expect to reach and capture the city by July 1, if all goes well.  Revised offensive plans, June 1, 1807 We roll north, crossing the Danube unexposed, while Napoleon himself leaves the army and relocates to Vienna. De Moncey and Lefevbre take over the pair of corps along the Sava/Danube confluence, while I have Mack holding Belgrade and Charles' large army swinging around their left. I think I can't leave this threat to my communications, but might need to fall on them from the rear:  I also have light cavalry, as usual, attempting to cut their communications. However, again, the French disengage and pull back. The real action late in June comes when Charles' advance corps, about 80,000 strong, comes upon Kellermann the elder (the younger Kellermann is a French general of division) leading his corps outside of Pest.  Kellerman, badly outnumbered, orders a withdrawal, but is caught against the river. Charles in turn keeps almost no reserves back, knowing that Warnecke is a few days behind and that he has Kellermann isolated. He orders an all-out assault against the French. It shows how far we've come as an army in just 18 months. Charles has grown from 4-4-4 stats (against Kellermann's 5-5-5) to a 5-7-7 commander - 7 is the max stat you can have! The leadership of Austria is top-tier at this point. Kellermann is an excellent general, better than anyone we have at the start of the game, but he's not good enough today. Caught attempting to withdraw over narrow pontoon bridges, Charles wins one of the first signal victories of hte war against the French:  Note that General L'Orme's division is all-but wiped out, taking 69 hits out of 70 hp. Several other French elements are destroyed, all of their horses and guns are captured, and only about 2,000 men escape over the Danube into Buda. Austria loses about 2300 men. It's a colossal debacle for France and morale soars back home. In the aftermath, with Wernecke following close on, and no serious French formations in sight, I order Charles to exploit the victory and cross the Danube against a second French corps under Lefebvre immediately:  In the south, Mack crosses the Sava near Belgrade to offer battle to De Moncey's corps:  I won't attack here, not yet, but I am pressing the French salient on both its flanks - soon I should be able to strangle their supplies, forcing de Moncey out into the open. For now, Mack covers our hinge of maneuver at Belgrade, while Joseph clears Hungary of the occupiers. By every measure, June has been a triumph for our arms! Situation at Budapest, July 1, 1807:  Napoleon has come down and taken command of a force of about 18,000 French, a small corps, just south of the city. He is badly exposed to both Charles and Warnecke's corps - Wernecke can cross, secure my rear, and Charles is free to march on Vienna with his 80,000 troops. In the south:  Mack's army faces de Moncey at Peterwardein, while my light cavalry steadily close the escape routes. Overview of objectives and losses:  France is down to a 2.3 power ratio to us - if I maintain the offensive and keep moving between his corps to hit them before he can concentrate, I have excellent chances. 1807 may be our most active year yet.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about. |