February 28th, 2023, 15:11

(This post was last modified: February 28th, 2023, 15:12 by Chevalier Mal Fet.)

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Historian's Corner: February - July 1, 1807

Quote:In the AGEOD timeline, remember, in 1805 rather than seek battle at Austerlitz Austria pulled back its armies into Hungary, yielding Austria proper to French invasion. The morale of the people was too high to accept peace with Napoleon, but with the French largely stationary along the Danube, the Habsburgs boldly launched an invasion of the ancestral enemy, the Ottomans, in spring of 1806. After heavy battles along the frontier, the Ottoman regular forces were largely defeated and the white-coated armies were able to march upon Constantinople. Despite heavy raiding along the supply lines in Serbia and Bulgaria, the Ottoman capital was taken at the end of 1806.

The rest of Europe was quiet, largely - with no peace of Pressburg, France did not conduct the intrigues regarding Hanover that provoked Prussia to war, so Prussia and France have remained at peace. Russia is largely fighting in the Caucasus against the Ottomans.

Austria spent the winter of 1807 regrouping her armies from the Ottoman campaign. Combat experience showed the superiority of the divisional organization, and many brigades, squadrons, and batteries were grouped into a total of 20 divisions (the most I am allowed to field at present), and an experimental corps was introduced, aping the French. In May, Archduke Charles led a counteroffensive beginning from Belgrade up the Danube to Pest, catching an isolated French corps there and destroying it under Kellermann in the middle of June. He is now in the midst of the French occupiers, who are scattered from Prague to Belgrade, with a large and concentrated army.

In Earth's timeline, Napoleon made peace with Austria after Austerlitz in 1805, then was driven into war with Prussia in 1806. He destroyed the Prussian army in a single month at the twin battles of Jena & Auerstadt, but Russia had come to Prussia's aid and the Prussian king fled to his ancestral capital of Konigsberg. In the winter of 1807, Napoleon pursued him into Poland, capturing Warsaw, and a surprise Russian winter offensive led to a bloody stalemate at Eylau in February, 1807.

Winter quarters, February - June, 1807

After the horrendous massacre at Eylau, both sides shakily drew back and settled in for the winter. Napoleon in particular, deep in Poland, grew concerned about his lines of supply stretching all the way back to the Rhine, and busied himself replacing the 60,000 men lost in the Eylau campaign and in securing his base. French garrisons were depleted of trained men and allies like the Dutch, Swiss, Italians, and Spanish brought up to fill their place. The Army of Italy was drawn upon for more men, more Italians taking their place, and the Class of 1808 was called to the colors 18 months ahead of schedule. Within weeks, Napoleon had assembled a new army of 100,000 men, placing in command his brother Jerome, Marshal Mortier, and overall Marshal Brune. VII Corps, shattered at Eylau, was quietly disbanded, and a new corps was created out of Poles, Germans, and Italians and placed under Marshal Lefebvre - X Corps. Thus, you can see in early 1807 that the Grande Armee was gradually becoming less French and more international in character.

All told, the French Empire fielded nearly 600,000 men in the spring of 1807. The Grande Armee, 200,000, was in Poland along the Vistula. Brune's new Army of Observation was in Germany, about 100,000 strong. Marmont's VIII Corps and the Army of Italy added 75,000 to the total, and the Army of Naples in southern Italy numbered 50,000 more. The balance, about 175,000 men, were strung along the coast of France and Holland to guard against British descents, or in various training camps, garrisons, and depot towns strung across Europe.

The Polish front, 1807, as represented by WoN. Danzig is at left, Konigsberg at center. Eylau is highlighted just south of Konigsberg. Friedland, shortly to enter our story, is just east of Eylau.

As the frozen Polish mud thawed, X Corps was dispatched to earn its place in the Grande Armee by capturing Danzig, a vital supply post along the Baltic. In Prussian hands, it could serve as a base to threaten Napoleon's links with northern Germany - taking it would secure his left and free him to focus fully on the offensive against the Russians. The siege proceeded slowly, but the Russian attempts to relieve the Prussian garrison were late and badly coordinated, coming only at the beginning of May. A bloody battle on May 15 sent the Russians reeling backwards, and Prussian general Kalkreuth surrendered the city with honors of war a week later, on the 22nd. Napoleon was now free to begin his offensive.

But once again it was Bennigsen who made the first move. As in January, in early June he attempted to catch Ney's VI Corps napping, and flung his men into a surprise offensive. Against 220,000 French, he could muster only 115,000 of his own men - 87,000 infantry, 11,000 cavalry, and 8,000 Cossack irregulars. His only real chance to hold Konigsberg, now that Danzig had fallen, was to catch Napoleon off-guard and beat his army piecemeal (much the same as our own Austrian strategy in alternate 1807).

Once again, Napoleon was caught off guard, but typically he reacted quickly. Ordering Davout, Bernadotte (who was wounded in the fighting, I Corps passing to General Victor) and Soult to Ney's aid, he remembered what had unseated his plans the previous February, and decided to turn it against the Russians. Two officers were unwittingly given false orders specifying a massive attack by Davout against Bennigsen's rear areas, and ordered to take routes that would lead them straight into the Cossacks. The saps couldn't be told of their purpose, however, and one of the heroic messengers performed prodigies of valor and made his way to Ney's headquarters, triumphantly reporting the success of his mission to Napoleon's considerable irritation. The other messenger, though, duly fell into Russian hands and Bennigsen was soon in full retreat north and east along the Alle river, towards his large fortified camp at Heilsburg.

Napoleon's summer offensive against Bennigsen, June 1807

The Emperor pursued, flinging Ney, Soult, Lannes, and Murat at Heilsburg while Mortier's VIII and Davout's III Corps swung around the Russian right, cutting them off from Konigsberg and driving them into the Prussian lake country to be destroyed. I Corps, under Victor, would contain the Prussian remnants around Konigsberg. Bennigsen duly turned at bay in Heilsburg to make his stand. One June 10, Napoleon galloped up to the camp and soon crested a large plateau that granted him a magnificent view of the Russian fortifications:

Quote:After arriving on the large flat plateau which crowned the height, the Emperor reined in his horse and leaped to the ground, calling out, "Berthier - my maps!" Immediately the Grand Equerry made a sign to the staff orderly bearing the portfolio of maps, opened the case and handed it to the Chief of Staff, who, hatless, spread an immense map onto the turf; onto this the Emperor advanced on his knees, then on all fours, and lastly at full length, using a small pencil to mark it up. In this position he remained for a full half an hour, in deep silence. In front of him, awaiting a sign or an order, stood the motionless grand dignitaries, their heads uncovered despite the blazing sun of a northern summer.

- de Norvins giving an eyewitness account of Napoleon at Heilsburg.

Despite Napoleon's commendable dedication to cartographical brilliance, the battle at Heilsburg proved another bloody check for the French. Bennigsen had 9 divisions firmly entrenched on either side of the river, but Napoleon, without waiting for the rest of the army to come up, immediately ordered bloody frontal assaults - similar to his mistakes at Eylau earlier that year. A day-long battle ensued with the Russians seeing off a series of poorly coordinated French attacks, and by the time fighting petered out at 11 pm, 12,000 Frenchmen and 6,000 Russians were dead, wounded, or captured. Both sides shared an unspoken truce on the 11th, policing the battlefield of the vast sea of casualties, and Napoleon belatedly decided to maneuver Bennigsen out of his stronghold. When the French threatened to get between the Russians and Konigsberg, the Russian general withdrew to the south bank of the Alle and began marching up the far side of the river on June 12th.

![[Image: xoSX7Ia.png]](https://i.imgur.com/xoSX7Ia.png)

Heilsberg to Friedland, June 12-14, 1807

The Alle describes a wide loop to the east between Heilsberg and Konigsberg, and Napoleon was on the chord of the arc, while the Russians were confined to the outside. The Emperor, when he saw the Russians had slipped away yet again from a bloody battlefield, threw his corps to the north to continue his efforts to cut the Russians off from the city. In order to beat Napoleon to the city - which had to be held, as the main supply base of the Russians and the last bastion of the Prussian monarchy - Bennigsen would have to pass through the junction town of Domnau. The only logical crossing place on the Alle Bennigsen had available was just down the road from that place - a small bridge town called Friedland. Napoleon accordingly put his entire army in motion for Domnau, with Davout on the right and Lannes flung out to hold the bridges at Friedland.

In a dispatch to Murat, dated "Eylau, the 13th", Napoleon wrote:

Quote:Marshal Lannes and his army corps are making for Lampasch but his cavalry heads for Domnau; Marshal Davout marches on Wittenberg; Marshal Soult left here at ten this morning for Kreuzburg. The First Corps [Victor] have reached Landsberg; Marshal Ney and Mortier are on the point of arriving at Eylau. Push forward your reconnaissance with vigor. If you can find a way of entering Konigsberg, you should allocate this task to Marshal Soult, for I would prefer my extreme left to occupy the place. Consequently you ought to instruct the marshal to make for the town without delay. IF this does take place, Marshal Davout will approach as close as possible.

Should the enemy army reach Domnau today, you will still push Marshal Soult towards Konigsberg, at the same time placing Marshal Davout in a position from which he can block the head of the enemy army between Domnau and Friedland. Write and tell Marshal Soult that if the enemy advances on Domnau in force, it will be of the utmost importance for the marshal to take possession of the town of Brandenburg, so that I shall have nothing to fear about my lines of communication which will be running to my left.

Clearly, the Emperor thought that Bennigsen was already over the river and concentrating at Domnau. He intended Lannes to cut his retreat, while Davout, Soult, and Murat flanked him and the rest of the army bowled him over. But there was no definite word on where the Russians were located on the 13th. Domnau was, apparently, deserted. Bennigsen was slower than he calculated - the Russian was still on the far side of the Alle, drawing near to Friedland. There was no way he'd be dumb enough to cross there, since the French were already astride the main road to Konigsberg and crossing would put a river directly across his line of retreat. Therefore, the Russian army was certainly moving up the Alle to the Pregel River, which they would follow down to Konigsberg.

However, Bennigsen was still more aggressive than Napoleon calculated. He had detected Lannes' isolated corps near Friedland, and gambled, in a repeat of his offensives in January and earlier in June, that he could cross, crush the lone force, and be back over the river before Napoleons' other corps could come to V Corps' aid. Napoleon had, indeed, taken great risks. Half his army, nearly 60,000 men, were marching on Konigsberg, which the Emperor thought was defended by 50,000 men. But there were only 25,000 there. The rest of his army was spread between Eylau and Friedland. SO, despite an overall preponderance of force in Poland, at the moment of battle the Russians would actually outnumber the French.

It wasn't until 9 pm on the night of the 13th that dispatches from Lannes arrived, indicating that strong bodies of the enemy were seen on the move near Friedland. Did this represent Bennigsen's entire army, or only part of it? Would he really cross at the town? Napoleon wrote to Lannes that night,

Quote:My staff officer arrived here a moment ago, but he cannot give me sufficient information to know whether it is the enemy army that is deploying through Friedland or only a part. In any case, Grouchy's division is already on the road, and when he reaches you he will immediately assume command of the cavalry under your orders. Marshal Mortier is also sending off his cavalry in support of yours, and is about to move off with his army corps. According to the news I receive, I may also send off Marshal Ney to your aid at one in the morning.

...

The Grand Duke of Berg [Murat] is at the gates of Konigsberg; a heavy bombardment against General L'Estocq [the hero of Eylau] can be heard. It appears that Marshal Soult has destroyed L'Estocq's rearguard at Kreuzburg; the firing and the bombardment lasted only half an hour and that makes us think the rear guard has been overthrown. The Grand Duke is only waiting to learn whether Domnau is occupied by the enemy before marching on Konigsberg itself with his infantry.

Marshal Davout is on the banks of the Frisching. I expect details at any moment. If, from the information extracted from your captives, you are certain that the enemy is not in force, I expect you to attack Friedland and make yourself master of this important post. If it proves necessary, the Ist Corps [Victor] can reach Domnau before ten in the morning. Write to me every two hours; send me the prisoners' interrogation reports. If you are at Friedland itself, send me the local magistrate with plenty of information.

All of Napoleon's attention was on Konigsberg. He was determined to take that place and secure his left. The skirmish Lannes was embroiling himself in at Friedland must surely be a sideshow - there was no chance Bennigsen would stick his neck into such an obvious trap as that.

Next Historian's Corner - Napoleon's Apogee: The Battle of Friedland, June 14, 1807

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

July, 1807 - Habsburg Revival?

Situation at the start of July 1807:

Charles, leading the Army of Italy (army names in AGEOD are auto-generated, by and large, but you can rename corps and smaller formations), is positioned just south of Ofen (modern day Budapest). The army of Italy consists of 82,000 men under Charles' personal command, and I Korps, our first experiment with the French corps d'armee system, 67,000 men led by General Wernecke. Archduke Joseph leads an attached battlegroup of 26,000 in reserve, marching towards Pest from deeper in Hungary, though he is not part of the official chain of command (ie his men won't join ours in battle, but I am moving him in operational support of Charles). All told, then, we have nearly 175,000 men massed along the middle Danube. Off-screen, General Mack leads 50,000 men in the Royal Army at Belgrade, linking Charles with the remainder of our forces in the Balkans, while Archdukes Ludwig, Ferdinand, and General Reisch lead small battlegroups of 15,000 men each pacifying Ottoman remnants. I have nearly 275,000 mobile forces at my command.

The Grande Armee, estimated at 200,000 men total strength, has spread itself out occupying Austria, and has spent much of the last 9 months chasing Austrian cavalry marauders around Dalmatia, Illyria, the Austrian Alps, etc. The Emperor himself and a few corps have made attacks on Belgrade, but perhaps unable to support themselves in that country, have withdrawn every time. Napoleon has recently taken over a small corps-sized force just to our south, while to the north general Lefebvre leads another corps upon our rear. Murat leads the largest formation identified, we know we defeated Davout over the winter so he's accounted for, and we just annihilated Kellermann's corps two weeks ago.

By and large there is no single concentrated force capable of meeting the army of Italy with anything like even numbers, and I trust Charles to handle himself against anyone but Napoleon. Accordingly, I order him to sweep northwest and liberate Vienna, which seems to be undefended. Warnecke will shield the left flank and keep the French army in Croatia from interfering. Mack will cautiously move up to Peterwardein, which seems lightly held, to liberate that fortress and shorten our lines, while still serving hsi role as a link between the two wings.

July 2 sees a bloody clash between Mack and de Moncey at Peterwardein, as Mack loses 10,000 men pushing back de Moncey's stubborn corps:

Still, he holds the day - but it seems Napoleon wants to manuever against our center, as he moves his corps by rapid marches to fall upon Mack. Unfortunately, for once the Emperor is too late, and instead of linking up with de Moncey, arriving on the day of battle as he is wont to do, he is instead beaten in detail by Mack:

It's mostly a skirmish by number of men lost, but an entire French formation is dissolved in the aftermath - it seems that the long campaign, now entering its third year, is wearing on the Grande Armee. Napoleon having lost the small number of combat troops he actually had is forced to withdraw.

Discouraging but not disastrous for the emperor - but the real blow comes a week later. On July 8th, Lefebvre's corps, marching south, stumbles into the entire Army of Italy. During a hard morning's fighting, Marshal Lefebvre has his head carried off by a cannonball, and the leaderless French freeze long enough for Charles to outflank their position. The Battle of Paks sees an entire French corps captured, for miniscule Austrian losses:

It's an electrifying moral victory, showing that the Grande Armee is anything but invincible, and coupled with Kellermann has seen two French corps of over 30,000 men wiped off the board in the last month. Morale soars across Habsburg lands, and it's clear our summer counteroffensive is gathering momentum. By July 22nd, two weeks after Pacs, the hard-marching 80,000 men of the Army of Italy parade into Vienna in triumph:

I pause to take stock. There seem to be no major French forces along the upper Danube here, and I need to liberate important cities like Linz, Prague, and Pressburg. However, the important thing first and foremost is to defeat the remaining French army. If I can do that, the remaining French occupation will be easily swept aside, and I can even contemplate an invasion of Italy.

Most of the Grande Armee's formations seem to be concentrated in Croatia:

Bernadotte has I Corps at Peterwardein, while Mack has cautiously fallen back towards Belgrade, though he kept a bridgehead on the far side of the Sava. Savary has another force of unknown strength covering his communications at Bjelovar, just south of Pecs, de Moncey has a small corps facing Wernecke to the north at Graz, and Murat leads a major corps-sized formation at Karlstadt. Off-screen more French forces are marching upon Ragusa on the Dalmatian coast, now overseen by Napoleon himself.

Interestingly, all of these communications, now that I have recaptured Budapest and Vienna, run south of the Alps through the Laibach Gap and Fiume to Trieste. Wernecke and Charles are now behind the French left flank, at Graz, while Mack holds the front at Belgrade and the southern face of the salient is Ottoman territory. I propose the following operation:

The Army of Italy will mount a major operation aimed at the capture of Trieste, severing the Grande Armee's lines of communications, and then will seek to bring the army to battle and destroy it in Slovenia and Croatia. Mack's Royal Army will serve as the anvil for Charles' hammer, while Joseph and Wernecke's corps will link the two wings of the operation.

I shall keep Mack at Peterwardein, on the defensive, while Wernecke pushes de Moncey back and seizes the village of Laibach. Charles will speed south from Vienna through Graz and then move through the Ljubljana gap upon Trieste. I hope to accomplish this by the end of August. Then, we can turn east and wipe out a significant portion of the French OoB.

The marching orders are duly issued, and after only a few days' rest and celebration in the liberated capital, Charles' weary but high-spirited troopers once more take to the roads, marching south over their ancestral lands. I wish I could report any climactic encounters, but the first week of the operation is quiet. August 1 arrives with the following set up:

August and September might see me turn the tide of the war completely. If all goes well, we can spend the winter raising fresh corps, and be ready to invade northern Italy or southern Germany in 1808 with good prospects of success!

August objectives and win status:

March 2nd, 2023, 13:25

(This post was last modified: March 2nd, 2023, 13:28 by Chevalier Mal Fet.)

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Historian's Corner - June 14, 1807: The Battle of Friedland

Continuing to show the difference between reality and our AGEOD universe, in Earth's timeline, Napoleon at this time was not traipsing around the Balkans, but instead was far in the north, in East Prussia, continuing a long campaign against a Russian expeditionary army propping up the remnants of Prussia. When Danzig surrendered late in May, Napoleon was free to go over to the offensive against the last bastion of Konigsberg. His goal was to drive between that city and the Russians, driving them out of East Prussia and compelling King Frederick William to at last make peace. The Russians, retreating down the river Alle, spotted an isolated French corps - V Corps, under Lannes - at Friedland, and decided to try their luck.

The Battle of Friedland is an anomaly for Bennigsen. To this point, despite being heftily outnumbered by Napoleon, the Russian general (actually a Hanoverian exile, but never mind) had been aggressive and bold in his maneuvers, but still savvy enough to preserve his smaller army against Napoleon's efforts to destroy it. He had escaped Napoleon along the Narew River in December, when the Emperor first arrived on the Vistula. In February, he had taken the offensive against Ney, and when that failed, had skillfully extricated his army from the trap in the bloody draw of Eylau. In the first part of June, he had again attempted to knock out VI Corps, and again when Napoleon responded had managed to scramble back to Heilsburg and win another bloody defensive battle. The Russian army in Poland had mastered a stubborn tactical defensive during the day married to a strategic withdrawal during the night that left the French effectively nothing for all their losses.

And at Friedland Bennigsen threw that healthy tradition straight out the window.

The appalling stupidity of this battle can be determined pretty quickly with a glance at the map. Let's build it up. Consider that we have two armies - the Blues and the Greens, about equal in strength.

Now, let us further suppose that these armies lie on opposite banks of a river, like so:

For reasons unclear, the Green army decides to cross the river against the Blue army, and builds a series of bridges - for some reason at a narrow isthmus on the far side, with a village further choking traffic, and builds no bridges elsewhere, like so:

Let us suppose that there is a smaller stream and pond that runs into the river at just that point, dividing the ground beyond into two areas - one on the same side of his bridges, and one on the far side, thus:

Crossing the river, Green deploys part of his army naturally to cover his precious bridges, his only line of retreat over said river, like so:

But for some unaccountable reason, finally, he deploys the OTHER half of his army on the far side of the aforementioned stream, where it is out of contact with the half guarding his line of retreat. The final deployment:

The result, as you can see, is that everything depends on his left flank. IF that flank is beaten, then his right will have no path of retreat over the fatal river he has, for some reason, put at his back. Common sense would indicate that you either spread your bridges out, so they're not all built in the same damn place - perhaps some behind the right? Or that you would deploy your entire army where it COULD cover the bridges, and not deploy half of it on the far side of an impassable water barrier where it can't assist in its own defense! Instead, with the setup WE have, Green has made it so that Blue has only to defeat half his army - which can't be helped by the other half - and he'll bag the entire lot.

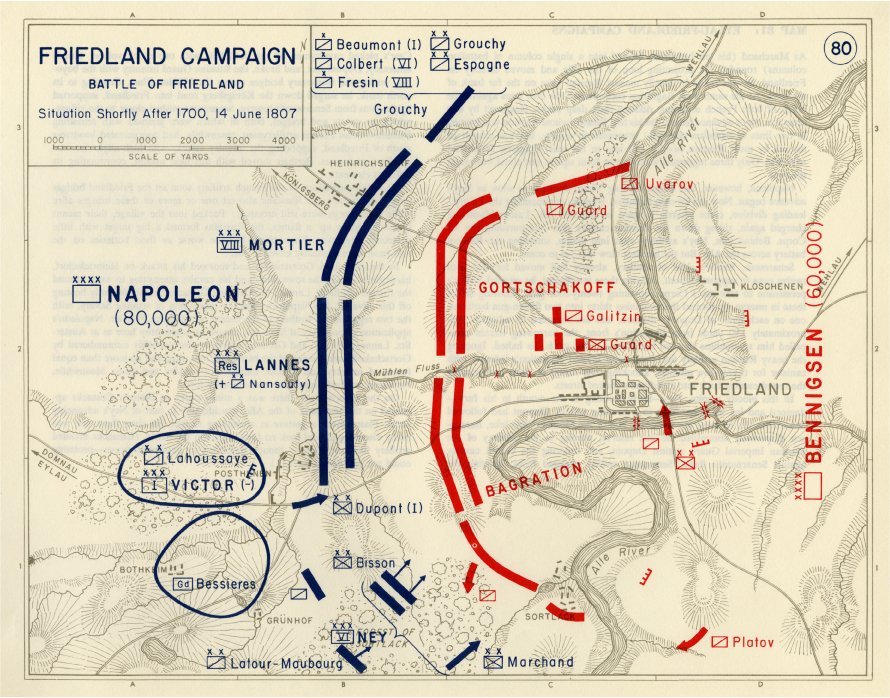

Now compare our hypothetical with the actual Russian deployment at Friedland:

...yeah.

Despite his aggressive plan of wiping out V Corps before Napoleon could respond, Bennigsen filed most of his army over 4 narrow pontoon bridges early in the morning on June 14 and proceeded to...sit on his ass, mostly. I've read that the commanding general was ill those days, and by the 14th he and his army had been straggling on the road for 4 days, with virtually no sleep, no food, and no rest. It's possible that his mind was fogged and his judgment compromised, but Bennigsen mechanically filed his divisions through Friedland's narrow streets and onto the fields beyond, into one of the most horribly compromised positions I've ever read of an army voluntarily assuming. Then, though, the Russian divisional generals made no aggressive moves against Lannes, but instead were content to hold their positions to absolutely no strategic purpose while Napoleon rushed reinforcements to the field. Mortier's VIII Corps, Lannes' VI Corps, Victor's I Corps, Grouchy's cavalry, the Guard - by noon the French had 40,000 men on the field and by 1700 over 90,000.

Lannes skirmished, bluffed, and cannonaded the enemy all morning, fighting a magnificent holding action -aided by the inexplicable Russian passivity. There were skirmishes and outpost struggles for various outlying villages, but no major attack. Many of Napoleon's staff thought it would be wise to delay the French counterattack until the next morning, when they could expect Murat and Davout to be able to join the field from Konigsberg. Napoleon, though, had other ideas. "No, no!" he exclaimed. "We can't hope to surprise the enemy making the same mistake twice."

Napoleon's maxim, "Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake," may well have been taken from Friedland, as he contentedly watched the Russians robotically funnel more and more troops over the river into the badly compromised Friedland position. Finally, with most of I Corps and the Guard up at about five in the afternoon, and having lulled Bennigsen and the Russians (and even his own officers) into thinking that there would be no battle that day, he ordered Ney to move in against the enemy left, overthrow them, and capture the vital bridges.

His orders read as follows

Quote:Marshal Ney will form up on the right between Posthenen and Sortlach, in support of General Oudinot's present position. Marshal Lannes will hold the center, his position extending from Heinrichsdorf to close by Posthenen. Oudinot's grenadiers, at present forming the right of Marshal Lannes, will incline slightly to their left so as to attract the enemy's position. Marshal Lannes will close up his divisions as much as possible so as to form two lines by Henrichsdorf and the Konigsberg road, and thence extending to face the Russian right wing. Marshal Mortier will never advance, as the movement be by our right, using the left as a pivot.

Quote:General d'Espagne's cavalry and General Grouchy's dragoons, together with the horsemen of the left wing, will maneuver so as to inflict the greatest possible harm on the enemy when he feels the necessity to retreat, pressed by the vigorous attack of our right.

General Victor and the Imperial Guard - both horse and foot - will form the reserve and will be positioned at Grunof, Bothkeim, and behind Posthenen.

Lahoussaye's dragoon division will be placed under General Victor's orders; Latour-Maubourg's dragoons will obey Marshal Ney; General Nansouty's heavy cavalry division will be at Marshal Lannes' disposal, and will fight alongside the cavalry of the army's Reserve Corps in the center.

I shall be found with the Reserve.

The advance must always be from the right, and the initiation of the movement must be left to Marshal Ney, who will await my order.

As soon as the right advances against the enemy, all the guns of the entire line will redouble their fire in the direction which will be most useful to protect the attack by the right wing.

Napoleon was exuberant - he knew this was a battle that he had won before it even started. Captain Marbot was one of the messengers who had ridden through the night from Lannes to bring word to the Emperor that the Russians were crossing at Friedland. "I found him radiating joy. He placed me beside him as we galloped onward, and I explained what had taken place before my departure from the battlefield. When my tale was told, the Emperor asked me, smiling, 'How good is your memory?' - 'Passable, Sire' - 'Well then, what anniversary is it today, the fourteenth of June?' - 'That of Marengo.' - Yes, yes,' replied the Emperor, 'that of Marengo, and I am going to beat the Russians just as I beat the Austrians!'

As the Emperor awaited his attack, cheering troopers road by in inspection, calling out, "Marengo! Marengo!" as they passed.

Napoleon reviews his cuirassiers, the afternoon of Friedland, 14 June 1807

At 5:30 pm, a triple salvo from 30 French guns announced the attack, and Ney's VI Corps emerged from Sortlach Wood - the considerable surprise of the Russians.

General Marchand's division, VI Corps, bayonets glinting in the late afternoon sun, headed straight for the church towers of Friedland. The Russian covering forces were bowled over and fled backwards towards the Alle, hotly pursued by the French. Bennigsen summoned up a cloud of Cossacks and other horse, flinging them at Marchand's flank - but against these paladins of the Steppe there rode out Latour-Maubourg's cavalry division. Sabers flashed in the sun, cavalry swirled, and soon the Russian horse was reeling back towards the village. The French advance resumed.

Bennigsen's next attempt to answer came from his artillery, massed - in one of his few smart decisions of the day - on the far bank of the Alle. Russian guns thundered fire and death, roundshot and canister enfilading the two divisions and Maubourg's horse. Most of the French casualties of the day were suffered in this bombardment, which temporarily halted Ney's advance. More Russian horse descended from the direction of the Mill Stream - the little stream separating the Russian army in two that day - and fell upon the French flank.

Now to the fore came Dupont's elite division, from Victor's I Corps. Also with him came Alexander Sernamont, commander of I Corps' artillery, leading with him 30 guns. Sernamont had been at Napoleon's side since Italy, and had long bounced tactical ideas off his old commander. Now he had a chance to put them into practice. The French guns, massed in a titanic grand battery, blasted the Russian guns off the heights opposite the stream. DuPont's division savaged the fresh wave of Russian cavalry, and soon the entire mass was whirling back through the already-disordered Russians in Freidland.

Sernamont put the finishing touches on the rout. Starting at 1600 yards, his gunners boldly rolled the pieces forward, belching shot at the densely-packed Russians rapidly filling up the narrow Friedland peninsula. Then they bounded forward to 600 yards, and fired again, then 300, then 150 - firing salvos each time. At last, Sernamont charged his guns to a mere 60 yards away from the by now reeling and disorganized Russian infantry. At point-blank, the French canister wrought carnage on the opponents, entire companies vanishing in a gory shambles in a salvo. The Russian right was unable to come to their comrades' aid on the left, so they launched an attack on Lannes and Mortier's two corps in the north - to no avail.

Panorama of Friedland, looking west from Bennigsen's headquarters atop the Alle. Friedland itself at foreground, the Mill Stream visible beyond. Ney's attack is visible at left, and the duel between Lannes, Mortier, and Gortachov on the right.

Bennigsen played his last card, throwing the Russian Imperial Guard as reinforcements over the stream - but they merely added to the chaotic traffic jam, as panic-stricken troops tried to flee back over the bridges and collided with the Guard attempting to force their way into Friedland.

By seven pm, a mere 90 minutes after the attack had started, Ney was master of the village and of the vital bridges. The entire French army advanced - Dupont taking the Russian center from the south flank, the rest of Victor's corps coming on north of the Mill Stream, Lannes and Mortier driving back the forces opposed to them. Seeing the flames consuming the village, aware of the collapse of their left, and faced with masses of French advancing on them, the Russian soldiers of the right flank wisely concluded that it was time to beat feet and that half of the army fled towards the river in panic.

A small ford was found in the north, the salvation of Bennigsen's army, but the Russians suffered terrible casualties nonetheless. Unit after unit straggled over the ford, dripping and wet but safe from French sabers and bayonets, and even some guns were extracted from the debacle, while the French were masters of the field. Napoleon had lost about 8,000 men, but in turn had killed or wounded more than 20,000 Russians, a third of Bennigsen's army. The Russians fled to the east, and beyond the Neimen river, hotly pursued by the French. Konigsberg was abandoned to Murat when word of the battle reached the city, and by June 19th the dashing marshal was watering his horses near Tilsit, on the Neimen. There, an envoy from the Tsar found him, asking for a truce. Russia was throwing in the towel - the War of the Fourth Coalition was finally over.

Next time - the Treaty of Tilsit

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Historian's Corner, July 1807: The Treaty of Tilsit

![[Image: 1024px-Tilsitz_1807.JPG]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/95/Tilsitz_1807.JPG/1024px-Tilsitz_1807.JPG)

"I hate the English as much as you do."

"Then we have already made peace."

Those were the first two sentences, it is said, that Tsar Alexander of Russia and Emperor Napoleon of France exchanged at their famous meeting at Tilsit. After two years of bloody conflict, Russia was bankrupt and exhausted. Her European allies had been defeated one by one, the French had advanced from the Rhine to the Neimen, and now Napoleon had smashed their last army, too. Alexander was ready for peace. Somewhat to his surprise, he found Napoleon eager for not just peace, but an alliance.

A raft was built in the Neimen river, now the frontline between the two empires, at the little town at Tilsit, and it was aboard this raft that the first face-to-face meeting between the two men took place. The interview lasted an hour and a half, on June 25th, and continued through two more weeks of diplomatic meetings and summits, marking the pinnacle of Napoleon's career - and the beginning of his slide into ruin.

I will gloss over it quickly. For two weeks, Napoleon and Alexander ate together, inspected their respective armies together, rode the countryside together, and gave every appearance of amiable friendship. The King and Queen of Prussia hovered around the fringes, nervous - and rightly so - of being abandoned amidst the rapprochement, but Napoleon refused to give them the time of day. On July 7, the first public Treaty of Tilsit was issued, between Russia and France - Prussia, humiliated and broken, was forced to sign a separate peace on July 9.

The terms set up an alliance between France and Russia, dividing Europe into two spheres of influence demarcated by the Vistula. Napoleon's ally Turkey was abandoned to the Russians, who were given free reign to take European Turkey in exchange for returning the Ionian Islands to France. Finland, also, was granted to Russia, and Russia was to act as a mediator between Britain and France. If no peace was forthcoming, Russia would join the Continental System and starve the recalcitrant islanders into submission. Denmark and Sweden would be browbeaten by both powers into following suit, and the Russian navy was pledged to help capture Gibraltar. There are rumors - unconfirmed, to my knowledge - that Russia also secretly agreed to the overthrow of the Bourbons in Spain and the Braganzas in Portugal, with a Bonaparte placed on each throne.

Prussia was treated far more harshly. Completely occupied and prostrate, she would be returned only the duchies of Brandenburg, Silesia, Pomerania, and East Prussia, as well as those parts of Magdeburg on the east bank of the Elbe. The great fortress city itself would not be returned, nor any of Prussia's trans-Elbe possessions. These would all be joined together with some other German states into the new Kingdom of Westphalia, with the Emperor's brother Jerome Bonaparte on the throne. The Polish provinces, which Prussia had so recently taken, would be stripped away and used to create a new Grand Duchy of Warsaw - Russia would not countenance a revival of the Kingdom of Poland - and Danzig would become a free city under French occupation. Further, a massive indemnity was leveled on the Hohenzollerns, and the country was to be occupied until it was paid in full. Finally, Frederick William was forced to acknowledge the Bonaparte kingdoms - Louis in Holland, Joseph in Naples, and Jerome in Westphalia, acknowledge the new Confederation of the Rhine, and of course to join the Continental System. Tilsit was the lowest point of the Prussian monarchy, prior to the catastrophes awaiting it in the 20th century.

Napoleon left Tilsit satisfied that Alexander was his eternal friend. Others were less convinced - the Austrians, for example, noted that irreconcilable differences still existed between France and Russia, and that the alliance could not survive in the long run. The Continental System chafed everyone who lived under it, and was widely flouted - attempts to enforce it would push Napoleon into wilder and wilder overreaches over the next few years, while Britain obviously weathered the embargo just fine. Prussia would eternally hate France for the humiliations inflicted on it, and quietly began a re-armament and reform program that saw the Prussian army rise, phoenix-like, in five years to join in Napoleon's final overthrow. Napoleon had thrown Turkey by the wayside, and that state would not forget.

![[Image: 16628.png]](https://www.worldhistory.org/uploads/images/16628.png)

Even if the seeds of his ruin were already sown at Tilsit, though, we should appreciate Napoleon at his height. The French Empire stretched from Cadiz to the Neimen, undisputed by any remaining Continental foe. Despite the check at Eylau, the Grande Armee had proven once again its invincibility over any other power in Europe. True, the grognards - "the grumblers," as the veterans were known - were sick of war and longing for home, after years of campaigning, and morale was lower than it had been in the glorious autumn of 1805. True, the marshals were riven with jealousies and rivalries - Murat hated Lannes, nobody could stand Bernadotte, Davout was a bit of an ass...And true, the Imperial Guard was becoming a bit big for its boots, haughty and condescending for the common soldiers, despite the fact the Guard almost never got its bayonets dirty these days. And true, the army itself was less French and more international in character - Italians, Spaniards, Dutch, Saxons, Hanoverians, Germans, and Poles making up increasingly large contingents. And on top if it all, true, the British crown and the British people remained inveterately hostile, secure in their island fastness, and eager to flame any spark of resistance into a flame with their bottomless gold and invincible ships. But all those were problems for the future. For now, France was victorious, and at peace. Napoleon was the greatest conqueror since Charlemagne. That was enough.

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

August 1807

August is, disappointingly, quiet, as the French army mostly starts to withdraw across the rear of the Army of Italy into Austria. The main showdown is between Murat's force, about 75,000 French estimated, against Mack's 45,000:

Again, the strategic goal here is to pin him down while the Army of Italy cuts the supply line at Trieste and we can starve them out.

That city is taken by Charles on August 17:

Leaving us with this situation late in August:

Charles is at Trieste in the far left. Wernecke's I Korps is in the center, and Mack is visible at right. Josef is in the center. For the French, Bernadotte's corps is attempting to cut between Charles and Wernecke and escape north, Savary's force is defending the supply line to Peterswardein, and now Marois is holding that fortress. We've lost sight of Murat. I order Charles and Wernecke to attempt to intercept Bernadotte's retreat, while Joseph continues tightening the grip on the French at Peterswardein.

Murat reappears at the head of his cavalry on August 28, falling upon Joseph's battlegroup. It's a bloody stalemate:

Situation on the Peterswardein front, 1 September:

Murat and Savary have Joseph in a precarious position, while Mack is still blocked by Marois. I will attempt to use Archduke John's small division to flank Marois and reinforce Joseph, who will go over to the defensive and attempt to withdraw from Savary across the river to the north.

West of there, Charles has chased Bernadotte into Fiume:

He will assault the city while Warnecke cuts Bernadotte's escape path, then both generals head east to finish off the French and clear us to return to Vienna and Trieste.

Status at the end of the month:

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

September 1807

The Habsburg counteroffensive - Emperor Francis's memorial (is he still alive on my diplomacy screen? I must check), I have termed it - rolls on. A campaign-defining battle is developing around Peterwardein, on the scale of Austerlitz or Friedland.

If you glance back to August, you'll remember that the month ended with Bernadotte trapped at Fiume by Charles. On September 1, the Archduke pitches into the badly outnumbered French corps:

The Prince of Ponte Corvo has 40,000 men in 4 divisions, including one of elites. Faced with nearly four times that number of Austrians, his men actually fight magnificently to escape, losing a third of their number and inflicting half as many casualties on Charles. Bernadotte is badly mauled, but his corps manages to fight through the Austrians up the coast and make his escape towards the Alps.

The day also sees a minor skirmish between Murat's odd cavalry/artillery column and Joseph's battered task force:

Leaving us with this situation by mid-September:

Bernadotte is at left making for the Isonzo valley, just north of Trieste. Charles dispatches Warnecke to harry him and drive him out of Croatia, while he takes the bulk of his army to march east. Joseph, at center, is attempting to withdraw over the Sava River, while Murat has been engaging him all months. In the far east, against a Peterswardein that has only garrison troops, I order Mack to advance and tighten the ring, in what turns out to be a fateful move. All mobile forces are converging on Murat's army, which numbers some 80,000 men split into the various stacks.

Here's the sequence that ensues. First, Mack brushes against Junot, who leads the Peterswardein garrison:

The French successfully withdraw before Mack can get his attack sorted out, and 1500 French power vanishes...where?

Into the fortress itself - thus invisible on the map:

Mack's 1700 power worth of men are thus besieging Junot's 1500 power worth in Peterswardein fort - but just across the river is Molitor, with nearly 1600 more. Savary's stack is still available over at Angram, and Murat has slipped away. Archduke Charles is marching as rapidly as he can from the direction of Trieste but is still about two weeks away, and John is crossing the Danube to take up positions toward Ofen and link up with Josef, completing our encirclement.

First, though, Murat leads Molitor's men in a savage attack, coming over the river on September 22 and attempting to break Mack's siege lines at Peterswardein. Instead of the surprise attack that the dashing cavalry officer had gambled on, however, who should he stumble on but John's isolated division, making its way down to the Danube bridges? A furious battle develops as John desperately tries to hold his ground, sending to Mack for reinforcements - but the lack of coordination between the two armies rears its ugly head. Instead of practiced in cooperation and a clear chain of command, like Warnecke under Charles, John and Mack are prickly, proud, and unused to working together. Mack is slow to respond.

All morning, John feeds brigades into the grinder one by one, as the little hamlets along hsi front are consumed in the holocaust. A French brigade will storm in and tumble the Austrians out at bayonet point - then they are hammered by John's artillery, and a whitecoat counterattack tumbles the French out in turn. The fighting is protracted and bloody, from dawn until well into the afternoon. Messenger after messenger is sent to Mack, who takes his time getting organized, leaving a covering force in the siege lines, etc. Murat focuses too long on bludgeoning frontal attacks, as is his wont - "I only make plans in the face of the enemy!" he snaps, when a subordinate reminds him of his goal of relieving Junot - but force of French numbers prevails, as John's final reserves run out. First a trickle, then a flood of the Archduke's infantry make for the rear, and soon his entire command is routing. The Archduke himself is wounded by a shell fragment attempting to rally his men, and his unconscious body is carried to safety.

The French are temporary masters of the field, but disorganized, strung out - and as they begin to consolidate their victory, fresh Austrians suddenly erupt over the ridgelines: Mack has finally arrived. His troops, wearied from a long march under the sun but unbloodied, hurl themselves into Murat's tired and disorganized veterans, and soon the French are once again pushed back. As the sun sinks below the horizon, the battle stops more from exhaustion than anything else. The first day of the Battle of Peterswardein ends in a minor French victory, as John's force is shattered but Mack is fresh on the field, and the French are strung loose:

Note that about 20,000 French are locked up in the fort and visible on this count, but aren't cooperating with their brethren outside.

The next day, September 23, Mack begins to extend his lines and attempt to work around Murat's flank, while the marshal has ordered up Marois's division from the reserve across the river to join the main army. In a colossal blunder for the French, though, Marois becomes lost on his march in the early hours of the morning and stumbles headlong into Mack's outposts, his road carrying him right into the midst of the Austrian army. Despite about 40,000 French facing an equal number of Austrians, Marois's 4,000 men are forced to fight the battle alone that day, and his entire force is cut off, dispersed or captured:

Following the second day of the Battle of Peterswardein, the situation in Croatia is thus:

Mack is marching hard to fall upon the French rear, but is still mroe than a week away. Molitor is with a much-battered French force of about 35,000 opposite Mack's 40,000, while Junot with 20,000 is still locked up in the fortress. John's force is shattered and I will have to rebuild it with fresh conscripts. Note that I have highlighted Peterswardein - the Army of Dalmatia (Murat commanding), Junot's corps, Vandamme's corps, and a handful of loose artillery and supply units are locked up. Savary is less than a week's march away and could join attempts to relieve the fortress.

All told, Mack's 1300 effective power is besieging 1800 in the fortress and 650 more across the river, with 350 more nearby - thus he is outnumbered more than 2:1 for the next week until Charles can intervene. IF the French can concentrate, though - they are scattered in 3 separate armies, half of it besieged, and the other half split in two and on the wrong side of a river. We have an opportunity here to wipe out the entire French army of Dalmatia - at least 2 corps, plus possibly 2 more outside the fortress.

Situation at the start of October:

60,000 French prisoners added to 270,000 total casualties = 330,000 French losses vs. 430,000 Austrian. We have suffered massive losses mostly in garrisons, but the battles against the French and Ottomans have been bloody, too.

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

October - December, 1807

We finish out the year as our grand counteroffensive reaches most of its targets, and the French Army of Dalmatia remains in limbo at Peterswardein.

Early in October, the French mount another operation to relieve Peterswardein, the corps again coming over hte river at Mack, while Murat leads the Army of Dalmatia out in a sortie:

Initially, Mack has a numbers advantage over the 24,000 soldiers from the fortress, but he soon has 30,000 more marching on his rear. The battle is prolonged and bloody, as the Austrian commander first repulses Murat back into the fort, then turns with his weary 40,000 men and meets the second French corps in another slugging match. Despite being outnumbered overall, Mack's deft use of interior lines proves his growing reputation as a defender (3-4-4 stats now, a reliable commander) and the first day of Second Peterswardein ends in another heavy French defeat:

Both armies lie under arms all night October 1 and into October 2, an unspoken truce letting them police the battlefield of the thousands of dead and wounded soldiers. On the 3rd, Murat tries again. Again, Mack parries thrusts in front of him and behind him, in operations reminiscent of Caesar at Alesia, keeping a larger army locked up by cannily interposing his army between it:

The third day's battle is a bloody French debacle, as Austrian entrenched guns shatter successive frontal assaults launched by Murat, while on the other side French attempts to force the river over narrow pontoon bridges again meet a storm of Austrian fire, one of the bridges breaking and trapping an entire French division. Murat loses a quarter of his guns, a third of his men, and is now actually outnumbered - the 80,000 French in the Army of Dalmatia have been whittle down to just 25,000 remaining effectives by the end of Second Peterswardein.

Situation by October 8:

Molitor's relieving corps remains stuck on the wrong side of the Sava-Danube Canal, while Savary is locked up by Joseph a bit more distant. Mack is battered but stronger than Molitor, and has 3 French formations trapped in Peterswardein (see the little brown 3 next to the fort graphic?). Best news, though, is that Charles has arrived and is camped a single day's march from Molitor's siege camp along the canal. The French marshal will have to abandon his attempts to break through to Murat.

The next six weeks of October and November become a rapid chase across Croatia, as Savary and Molitor both attempt to break out to the north, across Austria, making for the security of the Alps. Mack remains bogged down outside Peterswardein, which is stoutly defended, although the garrison can no longer sorty.

Charles stays hot on Molitor and Savary's heels, catching their rearguards here and there and inflicting about a division's worth of losses on both, but no major battles take place that autumn and by mid-November the front lines stand thus:

Charles has returned in triumph to Vienna, his strike south to sever French communications largely successful - Bernadotte and Molitor escaped with savaged corps, but Murat and Junot can be written off. Now he is ready to resume the offensive along the Danube and restore Austria's former frontiers. Winter will soon close operations here, but I hope to advance at least to Linz and winter on the Traun River, with a Bavarian offensive in spring 1808.

South of the Alps, I Armee Korps has been on detached duty since September:

Wernecke's corps has besieged Soult with a small corps (about 60,000 vs 30,000, I estimate) in Venice, but like Peterswardein the siege is slow. I want to bring Mack here to take over duties alongside Joseph's task force, transferring Warnecke back to the northern theater to operate with Charles - probably via the Alpine passes and Innsbruck come spring. Mack is bogged down at his own siege, however. Numerous French garrisons are still at large in Austria - Leoben, Prague, Koniggratz, Eger, Innsbruck, and Ragusa are some notable ones. I will be putting together reserve corps to deal with them one at a time while the main armies will be targeted at knocking Bavaria and the Kingdom of the Italy out of the war in 1808.

The Siege of Peterswardein drags on:

Not sure how long their supplies will last, the bar is still full green, but I am patient here.

Interestingly, after 7 weeks of siege, Murat tries another sortie on November 22. It goes about as well as his previous breakout attempts:

Down to just about 12,000 French in the fort after that one, while Mack has been reinforced back up to strength at 45,000.

December shows that the French are dwindling fast in the fortress:

Hopefully I can take it by surrender or by storm before April opens campaigning in Italy.

Along the Danube, Charles closes the campaigning season by finally catching up to Molitor's remnants at the city of Linz, and immediately storming it:

Molitor's division is captured or scatters, and the Archduke will go into winter quarters here. We have almost completely liberated Austria now, and for the first time since 1800 we can begin to contemplate offensive operations against the French Empire.

Situation in Italy at the close of 1807:

Not visible is Soult's corps, besieged in Venice. Marmont with about 15,000, Soult with 30,000, and an Italian force of about 15,000 men face 75,000 Austrians under Warnecke and Joseph.

Situation along the Danube at the close of the year:

Grouchy's cavalry corps in Passau and small French garrisons visible - Molitor is just the leader as far as I know, with no men under his command left.

Will post about 1808 plans and goals soon. But we're back in Vienna and we intend to stay for the rest of the game, this time!

Posts: 6,471

Threads: 63

Joined: Sep 2006

What is happening with the Ottomans? Are you just working around the game essentially being bugged and not letting them sue for peace? Are you benefiting from your successes in that theater at all?

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

(March 7th, 2023, 13:59)sunrise089 Wrote: What is happening with the Ottomans? Are you just working around the game essentially being bugged and not letting them sue for peace? Are you benefiting from your successes in that theater at all?

All major cities with the exception of Tirana have been occupied. Most of 1807 was occupied with a slow offensive by a division-sized force into Greece, with sieges of Athens and Patras. They're small cities and small forces were involved, so I didn't report much on it, with no images. In Bulgaria, I had about 2 divisions garrisoning the major towns like Burgos, Edirne, and Constantinople while dealing with Ottoman bushwackers.

Eventually, I gave up on peace after the AI kept rejecting any sort of reasonable offer, so for now we're garrisoning and occupying the major cities and patrolling the roads. I successfully did this to Britain, Prussia, and Spain in my games as France, but fresh Ottos do keep slipping across the straits, so that's a worry.

I think I get a bit of cash, conscripts, and war supplies from the occupied cities, modified by the region's loyalty level. To improve that I've done things like declare martial law, and victories over France have raised my loyalty realm-wide since people like to back a winner. I don't have hard numbers from any individual city, since even large cities like Constantinople only give a comparative trickle - maybe an extra brigade's worth every year? If even? They add up en masse but there's not a strong snowball mechanic.

Posts: 3,937

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Winter, 1808

We enter 1808, somewhat...hopeful? For the first time since war broke out with France back in June, 1805. We retreated to Hungary in 1805, and in 1806 spent much of the year fighting our way to Constantinople. The early months of 1807, a year ago, saw us regroup our armies near Belgrade, and then launch a large counteroffensive head-on against the French, retaking Budapest and Vienna, before a massive wheel towards Trieste and the Adriatic that cut off most of the French Army of Dalmatia in, er, Dalmatia.

Along the way, we completely destroyed at least 3 French corps (Kellermann, Lefebvre, Junot), cut off Napoleon along the Adriatic coast, far from the Grand Armee, and managed to regain about 80% of our national territory. The resulting situation at the start of the fourth year of the game is thus:

Huge losses, higher htan any other power, but about half of those are replaceable garrison troops (auto-spawned in forts and depots), and France's losses aren't far behind - and many of those are the elite mobile units of the Grande Armee. Futhermore, France now only has 1.7x our power! Momentum is swinging.

At Peterswardein, the siege has now lasted three full months, through October, November, and December. Mack decides to celebrate the arrival of the new year with an attempt to storm the French stronghold:

Murat holds the breach, barely. 20% of Mack's army is killed or wounded, but the last French horses perish in the fighting. The cavalry marshal is now in command of pure infantry (and a shitload of guns).

The siege lasts two more weeks, when Mack finally overwhelms the final able-bodied defenders. Peterswardein falls on 19 January, 1808:

Apart from a small French dragoon regiment, foolishly attempting to escort a few captured guns all the way back to, uh, France, Croatia is now completely free of the enemy:

My intentions are to put Mack into winter quarters until the weather clears, then he will march for either Italy or possibly help clear the Dalmatian coast first - Napoleon is ensconced with one last major French garrison in the lovely seaside town of Ragusa.

Further north, Charles had taken the Army of Italy into winter quarters at Linz, when spies bring him word of a French blunder. Emmanuel Grouchy has placed his corps into quarters at Salzburg, less than a week's march away - and he has neglected his patrols. In a daring winter march, on 8 January the Army of Italy slips out of its cantonments in cozy Linz, braves the wild wind and snow along hte lower slopes of the Alps, and has Salzburg surrounded before Grouchy knows Charles has even taken the field. As the French begin to stagger out of bed to the sound of gunfire, howling Austrians come over the walls and into the streets of Salzburg. Grouchy's resistance is fierce but brief and futile, and absent a few fugitives the entire corps is killed or captured:

The battle of Salzburg takes a 4th French corps out of hte order of battle and is Charles' greatest victory yet. The Archduke is a hero across the entire empire at this point, the most widely recognized and talented soldier on the Continent - after Bonaparte, of course.

The situation after the Battle of Salzburg:

Bessieres, with a few divisions of reinforcements for Grouchy, is left in the cold, literally, and will have to fall back towards Munich. Charles will now cozily winter at Salzburg instead of Linz.

The last major action of the winter season comes on 8 February, in Italy. General Warnecke's I Korps has been besieging Soult's corps of about 36,000 in Venice since October. With careful use of spies and siege works, by late January the Korps is at last ready to assault. Soult and Ney, the two marshals in the seaside city, have many support troops but only a few combat infantry, and the battle is surprisingly easy once the Austrians are over the walls. Another French corps, done for:

5,000 Austrians fall, but they account for 4 times their number in French casualties, and the other half of the French corps becomes prisoners. The situation in Italy at the opening of March is thus:

Joseph's battlegroup holds the line of the Brenta, just opposite Padua, while combined French and Kingdom of Italy forces under Marshals Marmont and Brune hold the far side. Warnecke is to the rear, but will not campaign in this theater - when the snow lifts from the Brenner pass he will be marching to reinforce Charles along the Danube. Mack will take over offensive duties in this theater.

We have three major objectives, after Venice, in the Italian theater:

Milan, in the center of the Po river valley, is the key to the peninsula. Taking this important city, the capital of the Kingdom of Italy, will knock Napoleon's puppet out of the war and mostly sever French forces in the peninsula - stretching down to Naples - from the metropole. Second most important is Turin, former capital of Savoy, under occupation by the French since 1796. Regaining this will eject the French from Italy entirely and push the frontier back to its position at the start of the Revolution. Finally, south of the mountains near Genoa, Firenze/Florence dominates the Tuscan plain. Its fall will solidify our control of northern Italy - only Rome and Naples will remain to the south, and they are or will be nominally independent powers.

My exact plan of campaign here depends on French defenses, but in general I intend to outflank them along the Po, not assaulting over the various river lines, in a rough analogue of Napoleon's 1796 campaign, but in reverse.

In Germany, here are our objectives for 1808:

First and foremost is Munich, which will knock the Kingdom of Bavaria out of the war. At the head of the Danube is the city of Ulm, a key to controlling southern Germany and a good base for operations along the Rhine. Far to the north, Frankfurt on the Main will anchor us on the Danube, shield Hanover, Kessel, and Prussia from Napoleon's influence, and cover our right flank as we undertake offensives into France. The last major objective we have in this area, not pictured, is the Swiss city of Zurich.

Taking all objectives in both theaters will leave us with only the objective cities of Prussia and Russia to capture: Breslau, in Silesia (lost since Frederick the Great!), and most significantly, the island of Corfu in the Adriatic (taken by Russia from France during earlier campaigns) and Kiev in the Ukraine. The Russian cities we will save for last.

The spring campaign gets underway at the Battle of Linz, which breaks out on March 1. Nicholas Oudinot, attempting to extract his corps from Leoben, has marched all the way around the flank of the Alps, skirting between those mountains and the river. At Linz, though, he finds Charles' Army of Italy, reinforced to 100,000 strong, barring his way. In a bloody battle, 40% of the French corps becomes casualties:

Charles keeps on Oudinot, pursuing him across the Traun River into Bohemia, and a few days later on 5 March he catches up with the survivors at Passau:

He marches to the upper Bohemian border, near Munich, where there is a French army approximately 100,000 strong facing him:

Charles will wait for Warnecke's 65,000 to reinforce before he goes on the offensive here.

See the French composition - note that Kellermann has a new corps. There is also a division of Bavarians.

Situation by the end of March - Warnecke has come up to Innsbruck. I need to contemplate how to crush this nut, the mountains and rivers make an interesting tactical puzzle for April.

That same week, in the south, Mack nears Napoleon at Ragusa:

[screeenshot]https://i.imgur.com/yw4Tei1.png[/screenshot]

It'll be a tough fight but the Emperor is cut off from supply and reinforcements, with nowhere to run. We can win this.

overall situation in the Balkans, 1 April 1808:

We own the roads and major cities, the Ottomans still hold the hills.

And in the north:

Austria is liberated, and an army is marching ot relieve Bohemia under Archduke John.

OVerall status at the end of winter:

France is down to 1.33x our power - we knocked off 20% of France's total power over the winter months. If I can beat Napoleon at Ragusa, Marmont in Italy, and Bessieres in Germany, we should largely have the war won this year.

|

![[Image: xoSX7Ia.png]](https://i.imgur.com/xoSX7Ia.png)

![[Image: xoSX7Ia.png]](https://i.imgur.com/xoSX7Ia.png)

![[Image: 1024px-Tilsitz_1807.JPG]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/95/Tilsitz_1807.JPG/1024px-Tilsitz_1807.JPG)

![[Image: 16628.png]](https://www.worldhistory.org/uploads/images/16628.png)