How do you find the AI in this game? It seems not too scary, but I'm not sure how much that is due to your strong gameplay.

As a French person I feel like it's my duty to explain strikes to you. - AdrienIer |

|

Chevalier Plays AGEOD Let's Play/AAR

|

(March 8th, 2023, 17:16)Amicalola Wrote: How do you find the AI in this game? It seems not too scary, but I'm not sure how much that is due to your strong gameplay. It depends on the game. In Wars of Napoleon, the AI is very bad. The constantly shifting alliances and fronts give it a hard time choosing sensible objectives, and since armies are hand-built by the player instead of generated via event, it also turns out to be bad at force composition. As France, it's okay to play against solitaire because most of your path is scripted, recreating Napoleon's career, with a better ending, hopefully - but only okay, not fantastic. I'm finding as a Coalition player that the French AI gets very badly confused if you do something unexpected. The French did very well coming down on Vienna like a ton of bricks in 1805, and creditably enough pushing on to Budapest and then spreading out to capture important cities - even to the point of attempting to cut my supply lines into the Ottoman Empire with attacks on Belgrade and Transylvania. The trouble is, they didn't concentrate on those projects like a real Napoleon would have, instead sending only a few forces while others did things like chase cavalry around Bohemia or vacation in sunny Croatia. And then when I counter-attacked, it was totally unable to pick a sensible point to concentrate the Grande Armee to counterattack, instead coming at me piecemeal from all over the map. In the two-player games, like Rise of Prussia, Civil War II, Birth of America, Revolution Under Siege, or To End All Wars, the AI can give the player a fair challenge. The fronts are set, the opponents known, and you can do a lot with pre-scripted forces showing up at the right historical times. The AI is good at raiding weak points, concentrating against player armies, turning your flanks and cutting your supplies, making good use of defensive terrain and fortifications, etc. It's still obviously much stronger on the defense than on the offense, but nothing much you can do there. The best of all, I've heard, and per reports on the forum, is AGEOD's PBEM system, which works pretty smoothly and moves fast. That's where the games really shine, when two human intelligences with all their creativity and unpredictability, square off, and shows off the game's WEGO system to best effect. But I never have anyone to play with, so use the AI as a punching bag I must.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Spring 1808 - April - May

The spring offensives get under way in Bavaria and Dalmatia, but French counterpunches through the Alps and Bohemia inflict a few bloody noses, including a raid on Vienna. Italian Theater This front is quiet for these 8 weeks, mostly as we await Mack to storm Ragusa and kick Boney out, then make the long march up the coast to give us the muscle for an offensive here. The front on April 1...  Marshal Ney with a division-sized force just over the river... ...and the front on May 1:  Minor raids and jostling with cavalry, but both sides are content to hold their ground at the moment. One irritation is the inability to cover my right flank at Trent, which changes hands a few times as the French still have the use of the Brenner Pass. I need reinforcements here to actually close that route - most likely Joseph will shift there when Mack arrives to assume the main defense of Treviso-Venice. Dalmatia The biggest action, of course, is the storming of Ragusa. I can't afford a long siege here, so Mack and Ferdinand will move in force against Napoleon. Moving on April 1, they arrive at the city on April 12 and launch an immediate, bloody storm:    This is why tangling with the Emperor is so dangerous - even with a 2:1 advantage in numbers, losses are nearly even, as Mack loses about 20% of his force and Napoleon nearly 2/3 of his. The French army is largely destroyed, as most of the survivors surrender apart from a small garrison that flees into the citadel, and the Emperor and many of his principle officers (including, for example, Bernadotte and Junot) make their escape, either slipping away over the mountain rounds or taking a small boat across the Adriatic to Italy, I'm not sure. Ragusa surrenders a week later, by April 20th, and Mack is free to march up the coast to Italy. The slow-moving Marshal reports that he will need nearly 3 months to complete the movement, so we can't expect him to be available before August! Ferdinand is dispatched to reinforce Reisch's 2-division force, which has been struggling since October to successfully invade and subjugate Albania, home to a 20,000-man force of Ottoman die-hards:  There have been numerous clashes in the mountains around Tirana, with neither side gaining the upper hand, but no bloody or decisive battles, either. Typically just a few men on either side lost. Hopefully I can maneuver Reisch to join up with Ferdinand and that will tip the balance at last. Tirana is the last major Ottoman town on this side of the Aegean. Danube Theater  Here's my final orders regarding the Munich area. At first, I intended to turn the French right, pushing around the mountains from Innsbruck into Oberammergad and Starnburg in the French rear, while Charles held hte front. Then, I would endeavor to cut the Regensburg - Munich road to the north before moving in to attempt to destroy the French - but a powerful French cavalry corps moved around Charles' left through the mountains and rode hard to Vienna. I have no force other than the Army of Italy to really defend hte capital, so I reluctantly order Charles to relieve the city while Warnecke's I Korps will take over the defenses at Salzburg for the moment. Unexpectedly, the French attack south out of Munich, attempting to catch Warnecke as he's isolated:  I Korps avoids battle, though, and successfully reaches Salzburg and takes up defensive positions. Dupont's division, meanwhile, probes past Linz onto the Vienna road, while the French cavalry force has moved on to Brunn. Charles turns around to repel Dupont and take position on Warnecke's right, ready to begin the Bavarian offensive at last. Dupont is savaged, losing about 3000 men to 1000 Austrians, and the French regroup at Munich while Charles reaches Passau. Charles and Warnecke will both now march on parallel roads to the Inn. From here, I will now turn the French left and cross the Inn downstream of Munich, then cut the Regensburg road and turn their position from the north:  Over the next two weeks, first Charles and then Warnecke successfully cross at Landeshut, putting nearly 150,000 Austrians between the Franco-Bavarian army at Munich and the Danube river. Charles moves around into the French rear, while Warnecke launches an attack from the north. Meanwhile the French have been passing divisions through the Alps towards Vienna again.  Maneuvers around Munich, May 1. On May 2, I Korps encounters Bessiere's mostly Bavarian army north of Munich. The Germans put up a stout fight through most of the morning, but they are outnumbered 8:3. By afternoon, both flanks are overlapped and Bessieres (historically the commander of the Imperial Guard) is forced to attempt a withdrawal. The withdrawal disintegrates into a rout as the overwhelming numbers close in and half the Bavarians are left on the field. 3 days later, Charles catches the other half of the Bavarian army south of Munich, as he sweeps west around the city, closing the ring. This fight isn't as closely contested and the Bavarians skedaddle quickly, limiting losses on both sides:  The final day of the Battle of Munich comes the next day, May 6, as the last Bavarians are beaten outside the city and driven inside the walls by Charles and Warnecke's combined force:  Now, though, I need to relieve Vienna, which has had a few small French corps move through the mountain passes near Innsbruck to besiege our capital. Munich surrenders by May 15 and Charles is once again marching hard for the capital:  Having cleared off most of the powerful French force at Munich, now I am free to concentrate more on defending Vienna, but it will fall to raiders before I can get there - wiping out an (unorganized) division I had moved there in an attempt to garrison it.  Vienna falls to a French raiding corps, May 17, 1808. Further north, you see why I can't fight the French without divisional organization. I can only raise 20, and most are concentrated into the Army of Italy (Charles, 6 divisions), I Korps (Warnecke, 5 divisions), and the Royal Army (Mack, 5 divisions), with 4 attempting to manage affairs in the Balkans (1 under Ferdinand, 2 under Reisch, and 1 defending the Constantinople - Edirne area against constant Ottoman harassment). John has no divisions, just loose brigades, and even though his total force is 30,000 men he can't properly manage his force on the battlefield - he's beaten by a 3-division force number 13,000 near Brunne:  One reason I thought I wouldn't be able to attack until 1810 was that is when I unlock free organization of divisions. Until then, the game only allows me to organize 20 total. Situation in Bavaria and Bohemia, 1 June:  Warnecke stormed Regensburg and effectively finished Bavaria, but I need to recall him to cover Vienna from threats out of the Alps. Meanwhile, the French poured reinforcements into Bohemia and it's clear John's corps (which is a formal corps now, albeit with no divisions) can't match them. Charles is at Vienna, and I think until my flanks north and south are secure I can't push deeper into Bavaria and certainly can't reach the Rhine. Italy will be secured when Mack arrives, at the end of July. Warnecke can then link up on the north side of the Alps if Charles takes the river. Thus, I think I need to use Charles in June and July to clear Bohemia of French invaders - wipe out the French stacks as best I can, leave the fortresses for John and Ludwig to clean up, and then they will cover his northern flank while Warnecke holds the Alpine roads to the rear and Mack covers the south. Then I'll be free to drive up the Danube for Ulm.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Summer of Discontent - June - August, 1808

After lengthy time in the mountains for spring break, I return to my computer and AGEOD. I play out the three summer months of 1808 today. June opens fairly auspiciously, as Charles' Army of Italy crosses the Danube at Vienna and meets one of the rampaging French corps near the small village of Wagram:  Hillier's corps is largely wiped out in the fighting. In our own timeline, in one year's time, Wagram becomes the scene of one of the most terrible battles in all of Napoleon's career, in 1809. For the future, however. That is about the only good news in June, though. The French continue to pour through the weakly-defended Alps, and now with Bohemia closed they turn south. St. Cyr's corps marches onto the north Italian plain, outflanking Joseph's defenders there and laying siege to Venice:  I am now badly outnumbered in Italy, and conclude I have no choice but to withdraw behind the Isonzo River. I give up the Piave and Tagliamento river lines, but I put myself closer to Mack's army moving up from Dalmatia. Mack should be in Trieste by the end of July, and I can contemplate an autumn campaign to regain Venice (again) and continue the war in Italy. For now, France has won this theater. In lower Moravia and Bohemia, Charles pursues the French cavalry corps wreaking so much havoc towards Tabor, but is unable to bring the French to bay:  He manages a few skirmishes, but by and large the cavalry are too quick to be caught by the Army of Italy, and too numerous for my smaller formations to deal with. They'd be vulnerable to losing supplies, except they largely live off the land, and the major cities in the area are still in French hands. The cavalry covers any attempt to besiege the cities with smaller formations. I need a major army, like Charles, to clear this area. Except, more French corps are pouring down the Danube. Warnecke is forced to retreat from Bavaria and is cut off at Passau. He beats the smaller French force, sort of:  But it's not decisive, and more French are moving on Vienna (again) while Warnecke is cut off. I have to bring back Charles to stabilize the line in this theater. Then, Charles' large, well-led army can hold the Danube line and Warnecke can clear Bohemia. I'm juggling armies a lot here, but I am more outnumbered than I anticipated at the start of spring. Situation by the start of July:  Through midsummer, the campaign along the Danube begins to turn in our favor. Charles marches from Tabor for Linz to link up with Warnecke and see off the French, while John's corps (now part of the Army of Italy in truth) moves north on Prague, after the French cavalry ride to Vienna. Lauriston, in command of French forces at Linz, attempts to break past Warnecke in Passau. The French lose thousands forcing the river and fighting through the Austrian entrenchments on July 13.  A solid victory at last, after June's setbacks. By July 16 the situation stands thus:  Lauriston's battered corps, only 25,000 strong, has mostly broken back towards Bavaria, though I hope Warnecke can rough him up on the way. Charles is crossing the Danube at Linz, just downriver from Warnecke's positions at Passau, and I again hope that both corps will be able to cooperate against Ornano's force - about 180,000 men concentrating on 30,000 Frenchmen or so should be another solid thumping. Ornano orders his men to abandon the river bank as Charles makes preparations for the crossing, and the Army of Italy finds Linz evacuated, crossing unopposed as the French move back with all speed for the relative safety of the Alps and the Bavarian borderlands. Lauriston, though, is still entangled in Warnecke's defenses at Passau, and now Charles moves through the vacated Linz to fall on the French rear on July 28. Warnecke assails from the front, and Lauriston loses half his remaining army fighting his way clear of the trap:  The two battles of Passau cost the French nearly 30,000 casualties in exchange for 7,000 Austrians, and I think that should quiet the Danube front for the rest of summer. Irritatingly, though, Lauriston's resistance prevents Warnecke marching to Vienna's relief, and my small garrison of the capital is put to the sword (again) by the marauding French cavalry corps (again). Situation along the Danube as of August 1:  I Korps is marching for Vienna, due to arrive August 5. Charles is moving the opposite direction to secure Munich and solidify our hold on Bavaria. By August, my plans are to use Charles to prevent more French incursions into either Austria or northern Italy, as best I can, while I Korps clears the French out north of the Danube and Mack/Joseph rest in Italy before beginning an autumn counteroffensive. Distressingly, apart from the capture of Munich, though, autumn is drawing near without my having made any appreciable gains against the French, although holding my ground against superior Frankish numbers is accomplishment enough, I suppose. Unexpectedly, Ornano moves his small battlegroup through the Alpine foothills not west, towards the Palatinate and Rhine, but east, and garrisons Vienna, arriving there before the sluggish I Korps. Warnecke has multiple times this summer failed in his marches, and Hohenzollern, his division commander, is jumped up to replace him:  Both have solid stats, and Hohenzollern has won enough battles with his division over the last 3 years that he actually is promoted to 3 stars, making him eligible for army command down the line. The remainder of August is as quiet as the war gets, these days - meaning still plenty of small battles raging, but nothing cataclysmic on the scale of the battle of Peterwardein (October 1807) or the Battle of Lorne (May 1806). For example, Hohenzollern retakes Vienna, and slaughters Hillier's division as it foolishly tries to cross the bridges into the city from Wagram, apparently unaware that it was once more in Habsburg hands. Meanwhile, Charles wins our furthest western victory yet, defeating a division of the Kingdom of Italy out in Memmigen, a crucial depot on the western border of Habsburg lands. We have now restored the frontier as far as Ulm, where we began 1805:   The Army of Italy is at center, in Memmigen. Strasbourg and the upper Rhine are visible at left. Our goal of reaching the frontiers of France by the end of the 1808 campaigning season is just about feasible, but our flanks are still vulnerable. The war in Bohemia - on August 1 John's corps (II Korps) reaches Prague and fights a sharp battle with Davout leading a reconstituted French battlegroup outside the city. This is familiar ground for us, having fought hard here with Frederick (in 1756, in our RoP game, and 1757, in reality). The French covering force is driven away from the Bohemian capital and we besiege the city:  John's force has only 1 formal division and a bunch of outdated brigades, so it's not as powerful as it will be in 2 years, but it's enough for our purposes now that the cavalry corps has moved off, and he is able to retake one of the most important cities in the Empire. Prague is stormed on the 2nd, St. Hilaire putting up only a token resistance before surrendering:  Situation in Bohemia by mid-August:  Here, I have one major corps (II Korps), with most of Bohemia and Moravia and Galicia under French occupation. Rampaging French corps have taken Krakow, Przcmyscl (fuck spelling that correctly, it's the big WWI fortress in Galicia), and Lemburg/Lublin over the summer. I also need to retake Koniggratz, Pilsen, and Eger in Bohemia. My intention is to use II Korps to retake Koniggratz (right center), and then move to secure Pilsen and Eger (visible at left) before moving to rejoin Charles for the 1809 campaign. I Korps will clear Brunn and and Olmutz (lower right) before moving to liberate Krakow (off-screen, right). I might then move back to the front and use follow-on forces to retake the Galician cities, not sure I want to divert an entire corps so far east. Finally, Italy over the summer:  In August, St. Cyr moved off south to invade Naples or something, out of my line of view, so I cautiously re-entered the Po plain with Joseph. Trevisa was regained without a shot, and I moved on Venice, driving a fairly large French force into the fortifications - the French were heavy on fixed guns and support units captured from Venice, but short on infantry, so didn't want to risk a fight. Joseph is ideal to keep Venice bottled up while Mack is resting at Trieste. Mack should be recovered from his long march and good to cross the Brenta, the first time we've done that in force since 1805, and recapture Padua, the last of our Italian possessions that has fallen into French hands. The real movement here will also have to wait for 1809, when I hope to be strong enough for an offensive towards Milan. Overall, the summer was a mixed-bag. I didn't gain nearly as much as I hoped to, after the nasty French counteroffensive in June, but I dare think that my armies are on a sounder deployment moving forward and we should make incremental gains through the fall campaigning season. I plan to finish 1808 before doing a historian's corner on what Napoleon was up to in our universe in the 18 months since the Treaty of Tilsit.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

I do enjoy these posts.

If I have any problem with them, it's that part of me keeps expecting Napoleon to pull a genuinely surprising, genius manuever out of the bag to shock you - but then I have to remind myself that, nope, it's just a computer. Ah well, give AI another decade ot two ...

It may have looked easy, but that is because it was done correctly - Brian Moore

Yeah, the way the AI models Napoleon is basically by giving him the highest possible stats and a metric button of abilities.

Most commanders have 0 or 1 abilities, things like "Staffer - gives +1 command point to his tack" or "Infantry leader - gives increased attack values to infantry." Some exceptional ones like Charles can have as many as 3 abilities. Napoleon, well...  On top of 6/7/7 stats (the max possible - he's literally always active and gives +35% to attack and defense values), he has nine abilities that combined make a Napoleon-led army virtually unbeatable.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Fall 1808

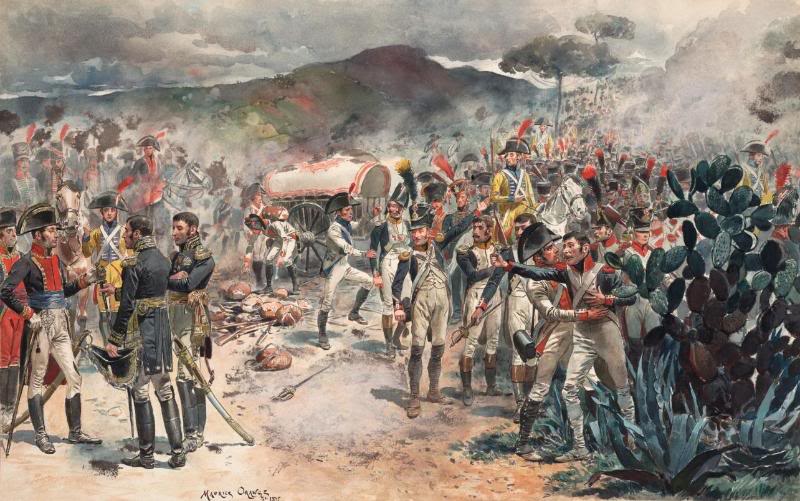

Score, objectives, and losses as of September:  Starting at top left and moving clockwise, VP gain is good - we're making more VPs than anyone except Russia and France, although they do have a hefty lead over us at about 8,000 points. If the game comes down to points Russia will probably win, since I expect we will continue to whittle France down. Objectives you can see are tumbling back - since the start of the Francis Offensive we have recovered Ofen, Vienna, Prague, Ragusa, and added Sarajevo, Belgrade, Bucharest, and Munich (currently shown as rebel-held since my garrison is too small, I think). We have lost Venice and Ulm from our starting objectives, but Venice is under siege and we are in striking distance of Ulm and Zurich. In fact, in Germany, we just need Frankfurt alone from French allies - everything else is Prussian. The Italian offensive needs Turin, Milan, and Florence in addition to Venice to be a success, but that is in reach within the next year. Losses screen - we are managing our own losses well enough. I have kept up, barely, with replacements through the summer offensive so most of our formations are up to strength, BUT we haven't been able to recruit any fresh brigades and my finances/conscripts are stretched thin. French losses are over 700,000 when totaling their prisoners, to our 650,000, and Frankish allies like the Bavarians have lost 40,000 more prisoners - which basically means the Bavarian army is done, more or less. French power is down to 1.2x our own, and in fact the History screen shows we have more men under arms than they do! Austria totals 400,000 between garrisons and mobile troops, France only fields 350,000 now. One area of concern is the Balkans. The Ottomans have assembled about 80,000 men into two armies, somehow - not sure how they managed it with no major cities, but they did. One army forced me to abandon the Albanian operations, pulling back from Tirana in August. I consolidated my Balkan occupation army into a single force, but it's still outnumbered:  This army has liberated Edirne, and my position around Constantinople is precarious. I've been spamming reasonable peace offers - basically Sarajevo, Belgrade, and a few connecting borderlands - leaving me with still well over 100 warscore unspent on the peace table, but the AI refuses anything and everything I offer. Fucking game. So we have our own Peninsular War going on, but it's diverting only about 50,000 of our total troops all told, and I can hold a while longer here. The followup goes badly:  I have one more division I can reinforce Ferdinand with, but that's all. I will attempt to consolidate the Army of Occupation in Istanbul and rest up for the winter, taking the field in the spring with fresh strength and hopefully scattering this Ottoman force.  Badly outnumbered in Thrace. However, when I join Ferdinand with the final division, his new 4-division force - a sizeable little army of 50,000 at full strength - is able to resist uncoordinated Ottoman attacks in Burgos all through the autumn. I can't yet move on Edirne, but at least I hold my ground and bloody the Sublime Porte a bit. In Italy, the major news is Mack is at last in position after marching all summer, and he storms Venice in the course of two battles at the end of September:   Numerous French support troops and a garrison infantry division are destroyed. The arrival of Mack's Royal Army and the disappearance of St. Cyr's corps means the balance has swung once more in the favor of Austria, to an extent greater than at any time since the Battle of Marengo back in 1800. Not only am I prepared to regain my final lost city (in this theater) of Padua, but further to press my advantage and capture the great fortress city of Mantua, key to the north Italian plain:  Joseph will take Padua and secure Mack's flank against threats from south of the Po, while the Field Marshal himself will place Mantua under siege. War against hte Kingdom of Italy should go well - it is a small country with a small replacement pool, brittle, like Bavaria and Wallachia were. -knock on wood.- In fact, it opens well as Mack manages to surround and capture an entire French division:  Final situation in Italy, November 1, the start of winter:  We are well positioned here to push south into Ferrarra, cut those Kingdom of Italy formations off from Milan, and then thrust on either side of the Po towards Milan in 1809. By 1810 in this theater I hope to be on the frontiers of France itself. In Bohemia, Lauriston and Ornano's rogue force is caught by I Korps at Brunn and badly mauled, but not destroyed:  Lauriston's 4 understrength divisions are on passive stance, which explains both their quick disengagement and our own light losses. Basically, the French are running, not fighting. Otherwise the counteroffensives here go well. Russian battlegroups emerge from the steppe and kick the French out of Lemberg and Krakow, leaving them just the fortress of Przsymszlskafakfasklfl in Galicia. Koniggratz surrenders with its entire sizeable garrison, leaving only a few French remnants in western Bohemia around Eger and Pilsen:  John's II Korps will complete the liberation of Bohemia over the winter. I Korps stumbles into a massive French force camped around Olmutz, as Napoleon gathers his various rogue corps in the north into one army. 40,000 French bravely defend the outskirts of Olmutz all day against twice that number of Austrians.  Period map of the Battle of Olmutz, 8 October 1808  Honors are even, probably slightly to the French given the disparity in numbers, but they can afford the losses far less than we can - they're deep behind enemy lines and have no prospects of reinforcement. October ends with most of the French survivors besieged in Olmutz, while the cavalry corps slipped away AGAIN and is AGAIN besieging Vienna. I will mop up Olmutz and then move south to (again) relieve the capital, with Moravia effectively liberated. In Bohemia, II Korps captures Pilsen when the garrison here, presumably upon finding out how well treated their comrades in Koniggratz were, also offer surrender. Only Eger holds out:  On the Danube front, Charles finds himself in striking distance of Zurich nothing seeming in front of him. I don't know if I can hold Zurich, but I can deal Switzerland a heavy blow and gain a good base for either an offensive down the Rhine to Frankfurt, OR into France itself:  Situation overall at the start of winter, 1808:

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Historian's Corner: 1808 in Reality (July 1807 - May, 1808)

With 1807 and 1808 in the rearview mirror, let's swap back into Earth's timeline and see what Napoleon got up to following the Treaty of Tilsit in July, 1807. In AGEOD's timeline, we continued our counteroffensive, with the bloody battle of Peterwardein in October, 1807, largely wiping out the French Army of Dalmatia and discomfiting them for the first half of 1808. In the late spring, fresh French corps launched a counteroffensive down the Danube and moved through Bohemia and Moravia as far as Galicia, while other reinforcements arrived in Spain. Summer and fall saw Austria reorganize its armies, with the Army of Italy and its two corps, I Korps and II Korps, clearing Bohemia and Moravia and pushing as far as the banks of the Rhine, while Mack's Royal Army joined Joseph in Italy and managed our first offensive successes in this theater, bloodily storming Mantua. In Rumelia, our Army of the Balkans under Ferdinand just managed to keep a lid on Ottoman resurgence, until Russian armies showed up to stabilize the situation. By contrast, the 18 months from July of 1807 to January 1809 were relatively peaceful for Napoleon. The British, deprived of Continental allies and with much of their army tied up in India, were reduced to raiding the periphery of Europe - failed expeditions to Alexandria and Buenos Aires, a more successful raid on Copenhagen seizing the 15 battleships of the neutral Danes. The economic war continued as Orders in Council were met with Milan Decrees as France and Britain tried to choke out each other's commerce. Napoleon feuded with the Pope, Foreign Minister Talleyrand ("a sack of shit in a silk stocking," Napoleon described him) resigned, and one little speck of trouble remained.  In the far corner of Europe, the small kingdom of Portugal continued to defy the Continental System. Britain's oldest ally offered Lisbon and the Tagus River as sanctuary for British warships blockading Europe, and was a point of transshipment for merchants evading Napoleon's counterblockade. Napoleon resolved to crush this last holdout to his authority on the mainland, and conspired with his ostensible Spanish allies to secretly march General Junot with 25,000 men through the peninsula to dismember the kingdom and drive the House of Braganza from power.  The king and queen of Portugal flee Lisbon, November 30, 1807 The operation went off more or less without a hitch. By December 1, 1807, Junot had marched his army across Spain and occupied Lisbon without a shot, the Braganzas fled to Brazil, and across Spain French troops were busily building depots and occupying key fortresses and crossroads, setting up a supply chain to their occupation in Portugal. And now Napoleon cast his covetous eye on Spain. Prior to 1808, most of Napoleon's wars had been defensive in nature. Austria and Russia had attacked him in the War of the Third Coalition in 1805, and Prussia and Russia conspired against him the War of the Fourth Coalition from 1806-1807. The Spanish adventure would be different. Here, Napoleon would betray and invade an ostensible ally, overthrow an ancient ruling house, and attempt to impose his own puppet government on a hostile populace. It proved to be one of his greatest blunders. "If I thought it would cost me 80,000 men, I wouldn't attempt it," he wrote, "but it will cost me no more than 12,000." In the end, over a quarter of a million Frenchmen and nearly a million Spaniards would die as a result of his catastrophic misjudgment. The root of the matter lay in the flaccid House of Bourbon on the Spanish throne. The ruling king, Charles IV, was weak and incompetent. His wife, Maria Luisa, was corrupt and decadent. She was openly devoted to Manuel Godoy, the "Prince of Peace," a jumped-up bodyguard made prime minister by the Queen, whose husband lazily delegated everything to. Godoy and Luisa, with the King's ear, were feuding openly with his son, Ferdinand, the heir to the throne and the hope of the Spanish people. Meanwhile, the Spanish army was corrupt, poorly administered, and basically helpless (it hadn't fought a major battle since the middle 17th century and hadn't won one in God-knows how long), the Spanish navy was mostly on the bottom of the sea after Trafalgar, and Spanish ports were flouting the Continental system. Would it not be better, Napoleon thought, to replace the weak House of Bourbon with a more energetic and reliable butt in the throne? He had the troops in place already, as the corps supporting Junot were occupying key positions around the country. Furthermore, a better ruler for Spain would further his war against Britain, as someone who could be trusted to actually enforce the Continental System. Thirdly, the weak and corrupt Spanish court could hardly offer resistance, and the Spanish people would probably thank him for freeing them from those jackasses. Accordingly, Napoleon lured Charles, Luisa, Godoy, and Ferdinand to Bayonne on the pretext of resolving their dispute, while more French reinforcements quietly fanned out across Spain. Then, in the late spring of 1808, he betrayed the Bourbons, throwing them into arrest, browbeating both men into abdicating, and placing his own brother, Joseph, on the throne of Spain. Marshal Murat, Napoleon's brother-in-law, was sent in with the cavalry to explain the new state of things to the populace. The Emperor, for once, had blundered, and badly. The Spanish people may not have had great love for the Bourbons, but they had even less for a French outsider, one who was practically atheist (a no-go in strongly Catholic Spain), beholden to his brother, and dragging them into a pointless, bloody war with the British. They did not take the coup lying down.  Dos de Mayo, by Goya, showing the Mameluks against the citizens of Madrid. On the Second of May, 1808, vast crowds took to the streets of Madrid, attempting to rescue members of the Royal family as Murat tried to have them arrested. It took only a few minutes before Murat decided the best course was to squash the rebels, and fast. He sent in the cavalry, including the dreaded Mameluks of the Guard, who had been following Napoleon since Egypt, but even as sabers flashed and the citizens of Madrid were massacred in the streets, the violence continued. It took nearly three hours to pacify the city, more or less. 150 Frenchmen and over 500 Spaniards were dead by the afternoon, and Murat clamped the city in irons. Cannon rumbled into the major junctions, cavalry swept the streets, and thousands of Spanish civilians were dragged to show trials and then, firing squads outside the city. Hundreds were put to death.  Tres de Mayo, Goya's most well-known work, showing the executions following the Second of May Uprising. Murat shakily wrote to Napoleon that he had things under control, but nothing could be further from the troop. By the end of May, spontaneous rebellions against the French puppet state were exploding in La Mancha, Estremadura, Valencia, Catalonia, Galicia - the governors of Badajoz, Cartagena, and Cadiz were assassinated - provincial "juntas," or councils of prominent local citizens, had seized control of Valencia, Asturias, and Seville, and were arming patriotic armies. The British immediately pledged support to the erupting Spanish rebellion, and sent a small expeditionary force under a young general Arthur Wellesly to Portugal, where Junot was isolated at the tail end of an enormously threatened supply line. By June, 1808, La Guerra de Independencia, as the Spanish called it, or the Peninsular War, as it would come to be known in Britain, was in full spring.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Winter 1808 - AGEOD

I meant to post this before the historian's corner for the relevant timeframe, oops. I can get through November and December relatively quickly. I. Danube Front The army of Italy largely rests, returning from its autumn raid through Switzerland to Memmingen, where it will go into winter quarters. There are a few clashes with loose French divisions under Oudinot and Hillier, none involving more than 8,000 French. These skirmishes go our way but are inconsequential. This front won't be come active again until spring. II. Bohemia - Moravia - Galicia Also largely quiet. Vienna falls, again, but the French raiders don't linger and are withdrawing rapidly up the valley of the Danube toward Linz-Passau. Early in November the French garrison at the fortress of Eger, on the western borders of Bohemia near Bavaria and Saxony, surrenders, the last real holdouts of the French invasion of 1805:  II Korps is ordered to move towards Munich to solidify the Army of Italy's LoCs towards Austria, and to be prepared to support Charles come spring. The French survivors at Olmutz surrender to I Korps, which marches back to Vienna and places it under siege. Hohenzollern is a terrible general, however, and is inactive all winter, so the siege drags on even as the walls are breached - I can't order an assault while the general is off chasing his mistress or whatever, enjoying the comforts of winter quarters along the Danube. Ass. III. Italy In Italy, our offensive against the Kingdom of Italy gets under way as we place Mantua under siege. Mack, though, overconfident, orders an assault, and contrives to get fully 1/3 of his army slaughtered by the miniscule Italian garrison. The 17,000 defenders lose 5,000 of their own number but slaughter 22,000 Austrians. Jesus.  My reinforcement screen is once again a shambles, as I'm missing over 200 hits. Each "hit" represents about 100 infantrymen or so. In order to replace the missing hits, you need to raise replacement companies - each company can be expected to replace more or less 10 hits. There's a bit of RNG involved, but on average 200 hits will need 20 companies. I can only raise 11 at the moment, so it'll be months before Mack is back up to full strength:  For what this level of damage looks like in practice, observe one of Mack's formations. Here's a look at Reisner's Division, Kaiserliche Armee:  When I have the division highlighted like this, over on the right you can see its component formations. Reisner leads 7 infantry regiments, 1 light regiment, 2 regiments of dragoons, and 2 infantry batteries. 6 of his 7 infantry regiments and his light regiment have been reduced to utter shambles, with only a handful of men remaining around the colors. Those hits will trickle back from my replacement depots over the next few weeks - if he's lost any elements entire, though (like a whole regiment), he'll need to rest on a depot for a few turns until a fresh one can be got up. After a few weeks of rest and refitting, the somewhat reduced Royal Army has another go at Mantua:  Storming a breach is always bloody business, and Mantua is one of the finest fortresses in all of Europe, protected by a complex network of lakes and bridges, but Mack gets it done, losing 9,000 to the defender's 12,000. North Italy by the end of November, 1808:  St. Cyr is encamped at Bologna with a few divisions of the Kingdom of Italy with him, about equaling Austrian forces in the region. I intend to rest for the winter here, with Joseph's battlegroup cutting the road between St. Cyr and Milan, refitting Mack back up to strength. Then, in 1809, I will form Joseph into a formal corps of the Royal Army, enabling the two stacks to cooperate (and boosting Joseph's command limit and stats), and attempt to envelop and destroy St. Cyr. Milan, Turin, and Florence are all goals for 1809. IV. The Balkans Here Ferdinand manages to keep a lid on things. At Burgos, he repulses several disorganized Ottoman assaults over the winter. The Ottos never press their attack too severely, though, and get off with light losses. They eventually tire and split their army in half, half remaining at Edirne and the other half moving towards Constantinople. Ferdinand presses up an attack on Edirne, and Russia has been flooding armies into the area to invade Anatolia from the rear:  Overall, a quiet winter but setting us up for a very optimistic 1809. It's distantly possible that the war with France will end next year in an Austrian victory.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about.

Historian's Corner, June 1808 - September 1808: Cracks in the Edifice

At first, Napoleon wasn't worried about the erupting war in Spain. He had 100,000 of the best soldiers in the world already occupying everywhere important in the country, the Spanish army was disarmed, the state leaderless. The peasants would calm down soon enough, especially once he delivered a few sharp lessons. He ordered his widely dispersed columns to go on the offensive. Murat, with 30,000 men, held Madrid, in the center. Further south, along the Tagus, was General Dupont with 24,000 soldiers. Marshal Bessieres led 13,000 men in various garrisons north of the capital and 12,000 more in Aragon. Junot was at Lisbon with his 25,000, and 13,000 more under Duhesme were in Catalonia. Against that, the Spanish Royal Army had perhaps 100,000 men, also in widely scattered garrisons, and a bunch of peasant militia and other rabble of no account (or so the Emperor supposed). This first effort to quell the uprising was a dismal failure. The French units, apart from Junot, were not the grognards of the German and Polish wars, but mostly raw conscripts from the class of 1808. The terrain was mountainous, the roads few, the population sparse. General Moncey was repulsed from Valencia but successfully fought his way back to Madrid, Dupont reached Cordoba but rising tides of militia combining with Spanish regulars soon compelled him to fall back to Andujar, Bessieres was forced to abandon an effort at Santander in the north, and in Aragon Saragossa (Zaragoza) heroically resisted a full-blown siege by a French regular division. By the end of June the French were everywhere in retreat.  Failed French assault on Zaragoza, 1808 Napoleon regrouped. Bessieres, holding the vital northern roads from Madrid to the Bay of Biscay and France, was to be given top priority. Second, Dupont, isolated far in the south, would be supported. The siege of Saragossa would be pressed vigorously to clear Aragon, and a renewed assault on Valencia would be made. Events soon outraced the Emperor in Bayonne, again, however. First, Bessieres routed a Spanish army at the Battle of Medina del Rio Seco, clearing the way to Madrid for King Joseph. More reinforcements would be hustled to Dupont. The Emperor said, Quote:Under the present conditions, General Dupont is the most important of all...If the enemy succeeds in holding the defiles of hte Sierra Morena it will be difficult to chase him out of them; consequently it is necessary to reinforce Dupont to a strength of 25,000 men. ...If Marshal Bessieres has been able to beat the Army of Galicia with few casualties and small effort, less than 8,000 troops being engaged, there can be no doubt that with 20,000 men General Dupont will be able to overthrow everybody he meets. Dupont had fought well as a divisional commander at Austerlitz and at Friedland, but his 23,000 men were conscripts, new to war, and the General was unused to independent command. But, even as the peasants of Andalucia swarmed to arms around him, and General Castanos marched on his position with 30,000 regulars of the Army of Andalucia, Dupont hesitated, unwilling to retreat to safety, until it was too late. When he at last began to fall back towards Madrid, he was encumbered with 500 wagons of loot and 1,200 on the sick list. On July 18, hearing that the passes ahead of him were held by the enemy, Dupont detached General Vedel's division, 10,000 men, to march ahead and clear the pass - splitting his army in the face of the enemy. By the 19th, the two French forces were separated by over 30 miles. The Spanish were not fools, and Castanos swept in, seizing the town of Bailen and placing 17,000 men between the French armies. At the same time, the rest of the Army of Andalucia fell upon Dupont's rear from Andujar. Trapped, the general sent frantic messages to Vedel to turn around and break the noose settling around him.  Five times on the 19th Dupont tried to break through at Bailen, five times his 13,000 conscripts and raw recruits were driven back by the Spanish force. At length, his men's morale collapsing and overcome with exhaustion, Dupont agreed to an armistice. For two days, the two sides glared at each other - Vedel appeared on the far side of Bailen, but the general concluded that discretion was the better part of valor, and no desperate attempt to cut a way through to Dupont was made. At length, running out of food and water, Dupont surrendered his corps to Castanos - including Vedel! On July 23 18,000 French soldiers were made prisoners of war, the largest surrender Napoleon's reign had ever seen. News of Bailen took Europe by storm. For four years, the Grande Armee had been invincible. No, it hadn't always won every battle - but it had certainly never lost! And now an entire army had been captured by Spanish peasants. It was the equivalent of Saratoga, 30 years before, on an even larger scale. The Pope was emboldened to openly denounce Napoleon, Prussian patriots quietly continued their program of re-armament, and, significantly, bellicose Austrians gained the upper hand in that state's cabinet and resolved to once more challenge the French Empire. Napoleon was incandescent with fury when he heard: Quote:"I send you these reports for your eyes only. Read them map in hand and you will agree that there has never been anything so stupid, so foolish or so cowardly since the world began...It is perfectly clear from Dupont's own report that everything was the result of the most inconceivable incapacity on his part. He seemed to do well enough as a divisional commander, but he has done horribly as a commander in chief." The Spanish paroled Dupont, but Napoleon threw him in prison anywhere, where he remained for the rest of Napoleon's reign. In fairness, Napoleon HAD thrown Dupont into an almost impossible situation, but the general made things worse for himself: Delaying his retreat until it was too late, deliberately dividing his command in the face of a numerically superior foe, and including Vedel in the surrender when that division had an open road to Madrid! Vedel had been slow to return to hte battlefield and incompetent when he arrived, and had failed to make good an open escape.  Capitulation at Bailen Dupont's disaster upended everything again in Spain. Joseph scuttled right back out of Madrid, Duhesme was thrown under siege in Barcelona, Zaragoza repulsed its French attackers, and then - more disaster, from Portugal now. In August a small British army led by Sir Arthur Wellesley, a 'sepoy general' who had made his reputation in India these last few years, newly returned to the Continent, landed in Portugal. At first, the hard-pressed French had bigger worries than the 14,000 redcoats (the British army had performed pathetically on land through the American Revolution and the early Napoleonic Wars), but Junot had dispersed his army to keep a lid on Portugal through the unrest. Now Wellesley punished him, moving like lightning through the scattered French and beating them at Obidos, Rolica, and then routing Junot's main body of 13,000 at Vimiero. Junot would have been in a sticky position indeed, except two newly arrived, more senior British generals took over for Wellesley and graciously agreed to evacuate Junot back to France - in British ships, with all their loot, no less. The Convention of Cintra infuriated British opinion (Wellesley managed to survive the scandal), but Portugal was free of the French yoke. Between Vimiero and Bailen, 40,000 soldiers, over a third of his army, had been temporarily removed from the order of battle for Napoleon. Enough was enough. Napoleon would do it himself. He ordered Mortier (VIII Corps), Victor (I Corps), and Ney (VI Corps) from their camps along the Elbe to march to the Pyrenees, tough veterans of the German wars. By the end of August, only Catalonia and Navarre - basically, Spain north of the Ebro alone - remained in French hands, which would become his base to restore the position in the Peninsula. While the armies moved once more across Europe, Napoleon settled his diplomacy elsewhere. He met with the Tsar at Erfurt, where some of the first cracks in the Franco-Russian alliance agreed to at Tilsit were starting to show. The Continental System hurt Russia's economy, while the Tsar was suspicious of the Duchy of Warsaw and of Napoleon's intriguing with Turkey, while Napoleon was fearful of Russian influence in the Mediterranean. Still, for now, in exchange for a free hand in Wallachia and Moldova, the Tsar reaffirmed the alliance, and by October 1808 Napoleon was in position and ready to lead a personal invasion of Spain.

I Think I'm Gwangju Like It Here

A blog about my adventures in Korea, and whatever else I feel like writing about. |