Posts: 3,920

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

I admit, I know very little about 19th century Swedish politics - pretty much only when it interacts with wider European history! So most of my writing is going to come from the French perspective. I'd definitely defer to the experts here.

AGEOD Winter 1810

In my initial conception of how this campaign would go, this was going to be the watershed year. This is the year that we would at last be able to form armies capable of facing the French in the open field, and winning. Charles Army Reforms are finally unlocked:

The Charles reforms simulate the reforms that Archduke Charles imposed on the Austrian army between 1805 and 1809, when the Habsburg army largely aped the French methods of organization and fighting. Light infantry and skirmisher tactics, permanently established divisions and corps - even without expert staff officers (in 1809 the Austrians were repeatedly hampered by the officers' lack of experience with the new model system, such as the tardy orders delivered to the right wing at Wagram) the Hasburgs fought much more efficiently and effectively than in 1805. Obviously these were all in place by 1809, so it's a little bullshit the game makes me wait until 1810 to implement them. This same year, the Russians (Barclay Army Reforms), British (Moore reforms) and Prussians (Scharnhorst) all get the same event, so in the second half of the game everyone can make modern armies.

In game terms, I can no longer recruit individual brigades, by and large, instead recruiting entire divisions at once. For example, here's my new roster of recruitable units:

Two (largely identical) models of infantry divisions, a Landwehr division, and various specialized brigades - grenzer light infantry, partisans, garrisons, etc. Before, I had to recruit about 3 infantry brigades (with 3 battalions each), some cavalry and artillery, attach an officer, and form them all up into a single division - this could only be done 20 times, then I had to use loose, hard-to-command brigades. So my armies were never as powerful as they should have been, and certainly nothing like the better-commanded French outside my two specialist formations, the Army of the Rhine and attached I Korps.

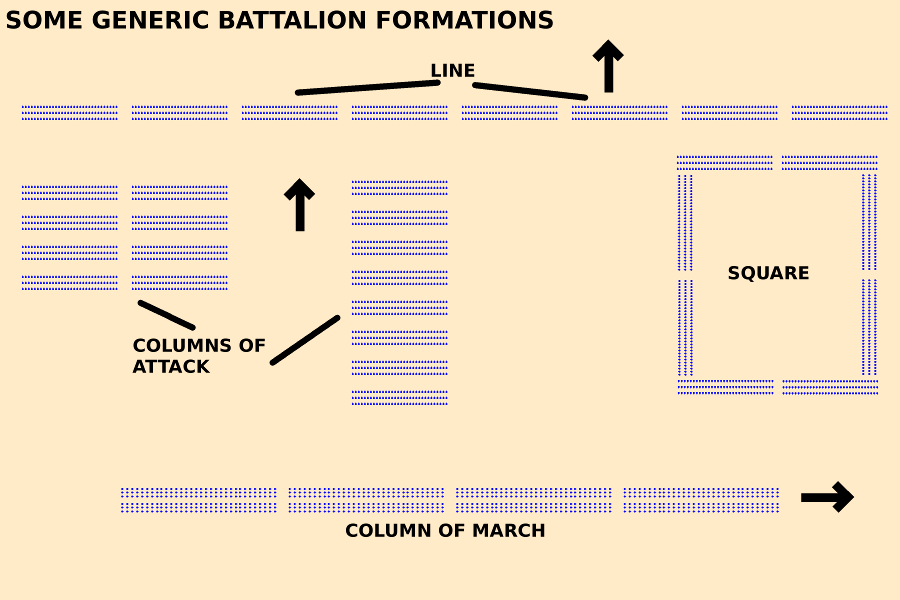

Now I can form corps freely, more or less, and recruit divisions straight from the depot. Each division has 9 infantry battalions and 3 artillery batteries organic to it - notably no organic cavalry, unlike French divisions, so I'll need to recruit those. A battalion is the basic fighting unit of the Napoleonic wars, at full strength 800 men strong in 8 companies:

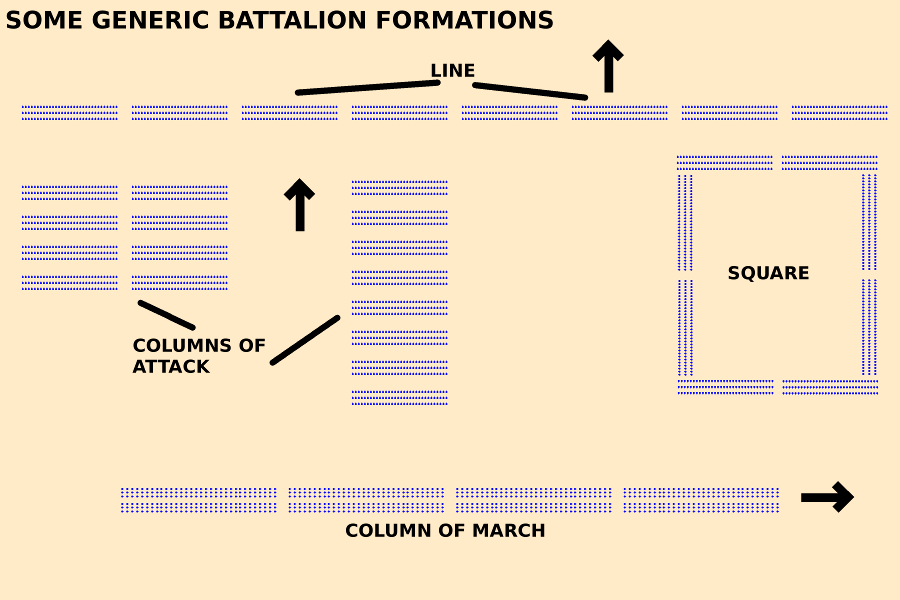

A battalion on the field. Square for repelling cavalry, line of march for movement. A line placed the battalion's companies all in line and brought maximum firepower to bear forward, but was very vulnerable on the flanks to cavalry and was difficult to maneuver or attack with. Columns of attack - either in division (2x4 formation) or by companies (1x8 formation) were quick to maneuver and had a lot of weight, but if the enemy didn't break before your arrival you would lose a firefight to a line.

Typically battalions would come 3 or 4 to a regiment - one would be the depot battalion, located in its recruitment area and with a few officers responsible for recruiting, training, and forwarding replacements to the field battalions on campaign. Ideally battalions fought together with their sisters, but often they'd be broken up and shuffled around according to the exigencies of the campaign.

Anyway, a division has 9 battalions, or about 7,200 men. The 3 brigades that would have a similar amount of men before cost 9 command points - now my divisions cost only 3 or 4 (I'm getting conflicting numbers). They also have organic 3 batteries, 8 guns with 120 gunners each, so all told I have about 7500 men and 24 cannon per division (the game doesn't distinguish between guns and howitzers, to my knowledge). I follow basic Napoleonic doctrine of 3 infantry divisions and 1 cavalry division per corps,* and spend the winter reorganizing my armies and recruiting out 3 full new corps for the coming final campaigns.

I do need to recruit more cavalry. So far I have mostly recruited hussar light cavalry, which operates as independent regiments for scouting and patrol work - the countryside doesn't magically flip to Austrian control, I have to send horsemen to actually ride around the district and get the peasants in line with the new order of things. However, my main armies have very low proportions of cavalry - historically the amount varied from 5 infantrymen to every trooper to 7 at the most per trooper, I have 10 or even 15 to 1. This means I don't inflict as many losses in battle and inflict very few losses at all in pursuit, while if I lost a battle I'd be very vulnerable to pursuit hits in return. So I'll try to integrate more horse into my armies. A cavalry division is 6 regiments of 400 men each, with a horse battery of 8 guns attached for some mobile firepower. The regiments are often in squadrons of 100-200 men each (average 150), but it seems the game doens't track individual squadrons anymore than it does infantry companies. Integrating these into the corps will increase my damage done in the assault phase of battles and the pursuit phase of victories.

It takes all winter and spring to march from France to Bohemia and reorganize the armies. Charles is locked in Vienna, and will be auto-retired at the end of the event, so I need a new commander in chief. I have a few 3-stars, of varying seniority. None are as talented as Charles, sadly, but by now my force is growing overwhelming. Here's the OOB of the two main field armies by May 1, 1810:

The Army of Bohemia, assembled around Koniggratz, is over 275,000 men strong with over 800 cannon. I am short about 30,000 cavalry, which is frankly a LOT of divisions (12!), so that's never going to get to recommended numbers. This massive force is greater than Prussia's entire field army and will avenge 1756-57, thrusting over the mountains to Breslau and liberating Silesia before turning on Berlin. I don't know if Saxony will stay neutral or join Prussia, but either way the Fourth Silesian War will show the Prussians how much we've learned since Frederick thrashed us.

- [li]Bellegarde, 3-2-3, is mediocre but my most senior marshal and so he receives the command, with about 30,000 men in the reserve.

[li]Schwarzenburg, 3-3-4, is the best man available in Bohemia but outranked. He leads I Korps, 70,000 of our most veteran troops backed by 176 cannon.

[li]Leichtenstein, 3-2-3, leads IV Korps, the largest formation of new model troops, 86,000 men with over 200 guns.

[li]John, 3-2-4, leads veteran II Korps, which will mass about 45,000 men with 225 guns once it's all assembled.

[li]Ludwig, 3-2-3, leads the new VI Korps, 41,000 men with 156 guns once all assembled.

Four corps should be more than enough to steamroll Prussia, and probably Russia too if I could just declare war on them. The game is over against any AI empire once I get this force in the field - it rivals what the Austrians fielded in the 1813 campaign and dwarfs what they could muster for the 1809 Danube campaign.

My intended plan of campaign is for one corps, most likely John's with its large number of guns, to head for Breslau to place that objective city under siege. Ludwig will take VI Korps to Ulm, falling back if he meets the main Prussian army, while the main army, I Korps, and IV Korps will move to Glogau to seize the gateway to Berlin, then move on that place to provoke Prussia into defending it.

Patrolling France, Italy, and Germany is Mack's Army of France:

- [li]Mack, 4-6-6, my most gifted leader now that Charles is out (each stat is just 1 below max!), leads 40,000 men with 80 guns in the central army reserve.

[li]Hessen-Homberg took over III Korps from Josef, 20,000 men with 136 guns.

[li]Kienmeyer, 2-0-2, a useless sack but very senior from his divisional command, leads V Korps, 43,500 men with 30 guns.

[li]Josef is forming the new VII Korps, 25,000 men with 80 guns.

This force has one operating in Italy, one in the south of France, and two in central and western France, gradually solidifying my control of the country. When war with Prussia comes, they will form a line against hte Low Countries, which ahve been overrun by the Prussians.

I also field Ferdinad with the Army of the Balkans, 36,000 men with 100 guns. Over the winter a large Ottoman force comes out of the hills and seizes Thessaloniki by a coup de main. Ferdinand embarks from his positions near Tirana with our new navy, sails around Greece, landing in Athens and marching up the coastal plain to the city, rather than forcing a difficult winter crossing over the mountains. A tidy little battle is fought and the city liberated:

Ferdinand's job is to keep the Ottomans suppressed. If war with Russia becomes possible, he will be our Corfu invasion force.

Together, then, I field over 440,000 combat troops, with many more in militia and garrisons that stretch from Rheims to Constantinople adding a further 200,000 static troops. We're in the endgame of the campaign, as I can confidently challenge any other empire on land. This is the last year, I think.

*Napoleon himself varied the exact compositions of his corps, not wanting the enemy to be able to accurately estimate the strength of a formation simply by identifying it, for example, as III Corps or as VII Corps.

April 1st, 2023, 18:42

(This post was last modified: April 1st, 2023, 18:43 by chumchu.)

Posts: 1,176

Threads: 12

Joined: Apr 2016

(March 30th, 2023, 16:10)shallow_thought Wrote: (March 30th, 2023, 15:26)chumchu Wrote: (March 30th, 2023, 11:36)Herman Gigglethorpe Wrote: (March 30th, 2023, 09:03)Chevalier Mal Fet Wrote: To be fair to myself, I was mostly giving Napoleon's perspective at that time. Bernadotte was no fool, but he was a bit of an uninspired battlefield commander. He could be vain, lazy, slow to take the initiative, and had bad battlefield instincts, but for all that he was brave, a good administrator, and well-intentioned. He was kind towards captured enemies, courteous towards foreigners (like Swedes or his Saxons), and had a knack for adapting himself to circumstances, a survival trait in turbulent Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. And, of course, Napoleon's harsh treatment of him comes back to bite the Emperor in the ass in a few years, while Bernadotte's descendants are still crowned heads in Europe.

When Bernadotte was mentioned, I was wondering what convinced the Swedes to make him their king. Did he look good in an ermine cape or something?

He was also chosen because he was 1) not connected to the old dynasty who had reinstated absolutism in the coup of 1772, 2) it was hoped that his military leadership and connection to Napoleon could help Sweden to regain Finland. It did not turn out as planned. He instead presided over an era of peace, cautious liberal reform, economic consolidation and investment in education and infrastructure. His reign is when Sweden transitions into a more peaceful nation.

Chumchu is likely better informed than I am, but my understanding is that it's as much as matter of the (extremely complex) internal and or Russian-focused Scandinavian politics as of anything else. I wouldn't take Wikipedia as a source of truth on anything too controversial, but lunchtime reading suggests the way that power shifted amongst the various parts there over time is fascinating.

I did my master on this stuff and it is hard for me to get a grip on it. You are right that is was due to quite complex internal politics. It is also helpful to zoom out a bit to get the big picture.

The three most important groups in early modern Sweden was the crown, the noble estate and the peasant estate. When two of these allied they could usually overpower the third one. In the 16:th century the nobles and the peasants allied against the Danish king and Sweden became independent under Gustav I. He allied with the peasants and consolidated power through establishing a network of loyal bailiffs and taking control of the church through the reformation. This brought his dynasty into a bloody conflict with the nobility and itself 1565-1600 ending with royal victory and the Linköping Bloodbath. The period saw the establishment of the Diet as the central political institution. The four estates (nobles, priests, burghers and peasants) had one vote each and the King was tiebreaker.

In the early 17:th century the crown and the nobility allied under Gustav II Adolf and Axel Oxenstierna. This allowed for increases in taxes and conscription to fund wars of conquest. The peasants opposed this but had a hard time stopping it as the new military state had a large standing army in Sweden at all times. The crown compensated the nobility heavily for its military service with crown land which increased its power. The noble estate became dominant during the regencies 1632-1644 and 1660-1672. This pushed the crown who wanted control over the state and peasants who feared that the nobles would reintroduce serfdom in Sweden into a new alliance. It was focused on getting reductions through in the Diet, the reclamation of lands handed out by the crown during the wars and regencies. This coalesced in 1680 with the Great Reduction giving the crown a financial base, the Allotment system giving the peasant clear rules for military service and the royal absolutism centralizing power.

The military of the absolute monarchy under Charles the XI and Charles XII was more powerful than that of Gustav II Adolf, but it's opponents had grown even more in strength. Sweden lost its overseas empire to Russia during the great Northern war 1700-1721. The war ruined Sweden. Roughly 20% of the population died in war, starvation and the plague. The economy went through a hyperinflation when the crown printed money to pay for the war. The rich Baltic provinces with their toll revenues were lost in the peace. This discredited the Crown and after the death of Charles XII without heir the Diet stepped into the void. Initially the nobles were dominant in the Diet. This was clearly felt in the debate of how to salvage the state budget. After the war it owed pay to soldiers and officers, compensation to peasants for war requisitions and money to lenders in Sweden and abroad. The Diet decided on compensating officers and lenders but not peasants and soldiers.

The politics in the diet were organized in loose factions, the most famous are the Hats and the Caps. The Hats had a larger following among the high nobility, were supported by France and wanted war with Russia. The Caps had more non-noble members, wanted peace, and supported more royal power and later got support from Russia. This came to a head when the Hat government invaded Russia 1741-1743 and failed miserably. This debacle and the choice of Adolf Fredrik as heir to appease Russia caused a peasant uprising/demonstration to reinstate Royal absolutism. The peasants political goal during the era was to get into the executive committee and to increase royal power. Their slogan at the time was "better one master than twenty", a reference to the twenty man executive committee. They had some success in this and Royal absolutism was reinstated in the military coup of 1772 by Gustav III. It limited the power of Nobility even if it did not deliver on all the hopes of the peasants. Incidentally, this also led Sweden to be the first nation to formally recognize the US in 1777 as Gustav III was really into enlightenment ideas. After another failed war against Russia Gustav III was assassinated in 1792 by a noble conspiracy.

In a typical way of absolute monarchies he was succeeded by failson who was a less competent administrator, politician and diplomat. Gustav IV was more conservative. He opposed the French revolution and loathed Napoleon which led him to declare war on France in 1805. Which as we can see from the thread was a profoundly stupid idea as France wanted Sweden as an ally in the continental system. Napoleon did not have the time to deal with Sweden then but he did give Russia his blessing to take Finland from Sweden in 1808-1809. The war is once again a Swedish failure. The plan was to trade space for time and let the Russian advance deep into Finland in 1808 while holding the key fort of Sveaborg in southern Finland. When they were stretched out maximally, Sweden was to counter attack in early 1809 from the North and from Sveaborg. Sveaborg however fell already in May 1808 and with it, the elite of the Swedish army. Gustav IV refused to sign peace and was deposed by a group of military officers with no one coming to his aid.

Karl XIII, brother of Gustav III, was chosen as new king. He had no heir and also had to grant significant power to the Diet. The first choice of heir by the Diet was the Danish prince Karl August, more popular among the peasants then the nobility. When he died there was an opening for Bernadotte. He was chosen to avoid choosing the son of Gustav IV, who might want to reinstate absolutism and to get back into the good grace of France and possibly re-take Finland. A reason for Bernadotte's success was that he cooperated well with the peasant and burgher estates in the diet on a common agenda of liberal reform. This slowly decreased the political power of the nobility without leading to a coup as happened to many of his predecessors. A large part of the nobility went into business during this period and their success there might also have blunted their opposition to his rule.

Posts: 3,920

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

(April 1st, 2023, 18:42)chumchu Wrote: The military of the absolute monarchy under Charles the XI and Charles XII was more powerful than that of Gustav II Adolf, but it's opponents had grown even more in strength. Sweden lost its overseas empire to Russia during the great Northern war 1700-1721. The war ruined Sweden. Roughly 20% of the population died in war, starvation and the plague. The economy went through a hyperinflation when the crown printed money to pay for the war. The rich Baltic provinces with their toll revenues were lost in the peace. This discredited the Crown and after the death of Charles XII without heir the Diet stepped into the void.

AGEOD does have a Great Northern War game, Wars of Succession, which has the GNW and War of Spanish Succession running in parallel. I own it but haven't played much with it - there's no corps system in that game and it takes me some getting used to.

Posts: 3,920

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

AGEOD Summer 1810 - The Fourth Silesian War

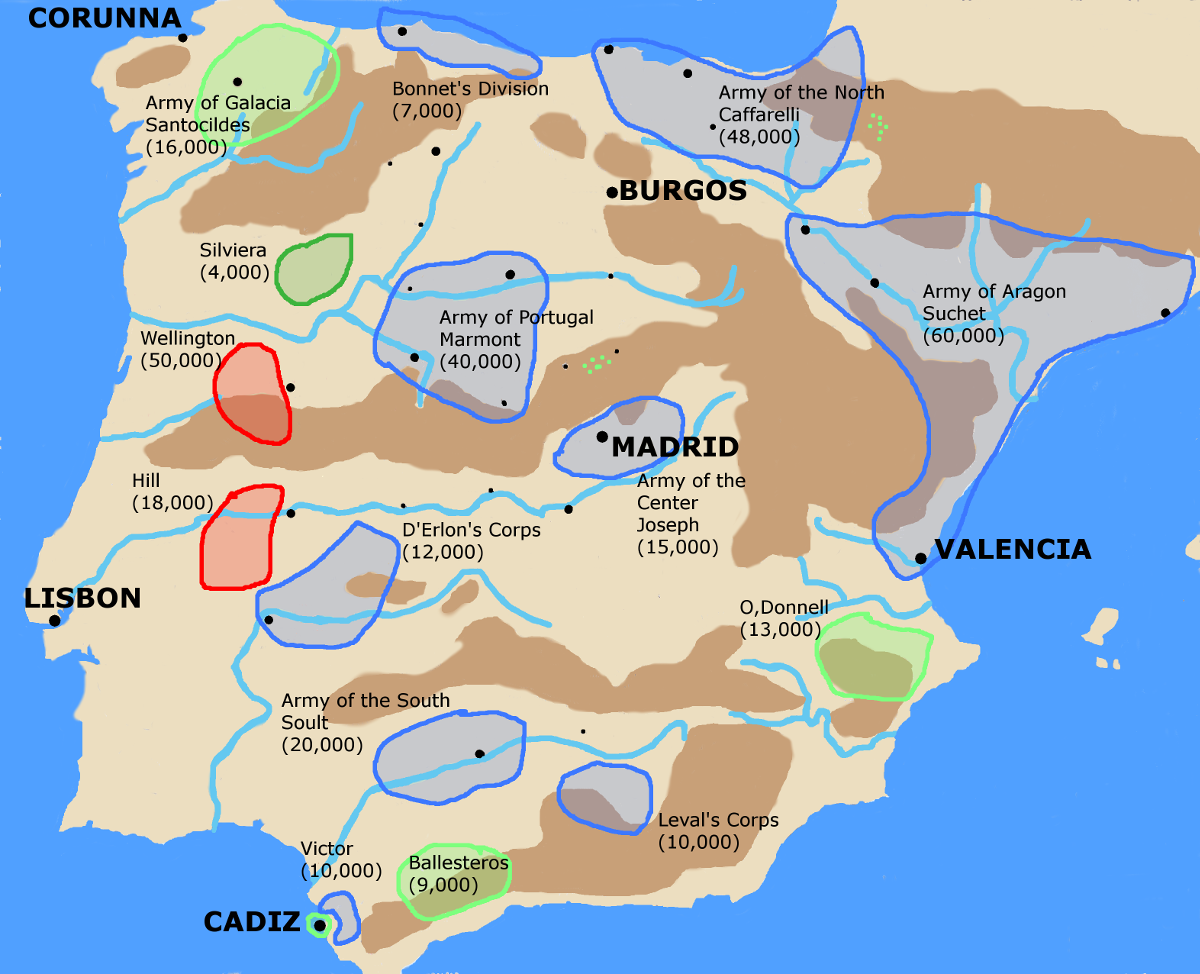

Situation at the beginning of May:

All objectives save Prussia and Russia secure. Our army is 2.5x the size of the surviving French, and about 1.5x that of Prussia. We aren't as strong as Britain or Russia, but Britain's army is mostly territorial militia, locked in England, and Russia has a vast frontier to defend.

By May 1, I decide the pull the trigger on the Fourth Silesian War (the fourth in 70 years). The first began when the young king Frederick of Prussia invaded our fairest and richest province back in 1741, thinking Queen Maria Theresa would be easy prey. By winter the entire province was in Prussian hands, and it stayed there through the battles of Mollwitz and Chotusitz the next two years before we signed an armistice. The Second Silesian War began in 1744 and saw our Austrian troops perform better at Hohenfriedburg and at Soor, but still not good enough to beat Frederick, and he retained the province still. The Third Silesian War broke out in 1756 when Frederick launched a pre-emptive strike against us and our allies in Saxony, invading Bohemia in the fall of 1756 and winning a decisive battle at Prague in November of that year. He followed up the destruction of the Habsburg army with an offensive on Vienna in the summer of 1757 before we could rebuild, and ended the war by storming our capital. There things have stood for half a century - now we have our revenge.

All the formations of the New Model Army, also known as the Army of Silesia, aren't fully assembled yet, but I don't anticipate Prussia stopping the 3 corps I already have assembled. Ludwig's projected VI Corps is at Regensburg, still forming up, but when it is it will be dispatched to Ulm, while the rest of hte army invades Silesia and then moves onto Brandenburg to exact revenge for Frederick's depravations. Mack's Army of France will fight Prussians all over that fair province, as well, and counter-invade the Low Countries when able.

The Army of Silesia gathered at Koniggratz, just over the Bohemian mountains from lost Silesia.

Saxony, nominally Prussia's ally, is neutral, blocking the direct road to Berlin. Intelligence suggests that most of Prussia's army is invading the Low Countries and northern France, where they'll meet Mack. That leaves Silesia vulnerable to just the sort of coup de main that Frederick pulled a few years ago. We will seize Breslau, capital of the province, and then swing north through Poland.

We'll need to take Lodz and Posen to secure our supply line, and Frankfurt-on-the-Oder as the gateway to Berlin. Again, cavalry scouts suggest there are no strong Prussian formations in Poland, so Warsaw could be taken by a detached corps at a leisure. It's not a victory city, though.

No movement on finding a way to attack Russia - can't leave the Coalition, can't make peace with Britain, can't load the game as either country and release Austria or declare war on Austria, so this is the final campaign, I expect. I'll wrap up this game at the close of 1810.

The invasion starts with minor clashes between Prussian border guards and our massive army of 200,000 moving in, nothing really to report. Within three weeks Breslau is encircled and our tentacles begin extending through Silesia:

Note the additions of West Prussia and Poland to the territories of Prussia since 1756. All Austrian soon enough.

Abruptly Bohemia and Bavaria are strongly invaded.

Prussia reacts within about 6 weeks. Frederick William surprises me, though - instead of shifting troops to defend his capital, the defense of Silesia, Brandenburg, and Poland is left to local regiments. The main Prussian army launches a counter-invasion of Bavaria and Bohemia, seizing the vital bridge Danube at Regensburg (and disrupting the assemblage of VI Corps there), while other forces push over the mountains in the west and seize Tabor and Pilsen:

Blucher ensconced at Regensburg, while Ludwig retreats over the Isar.

I react. I Korps and the reserve force of the Army of Silesia are ordered to move immediately on Berlin over the Oder - either we'll draw forces to us or we'll take the city and kick out Prussia's national morale. II Korps will defend my Polish flank. IV Korps will move back into Bohemia from Breslau, which was stormed at the end of June, and attempt to link up with Ludwig, cutting off the Prussian columns invading the province. I will also finish forming up VII Korps and III Korps, presently campaigning in Italy, and bring them through the Alps to the Upper Danube/Rhine area, where they link up with Mack. V Korps is left alone to deal with policing France. The Army of the Balkans is loaded on transports from its campaigning area in the Peloponnese and shipped to the head of the Adriatic at Trieste, where it will march to Vienna and assume the defense there.

In many ways, this massive movement of men all across Europe resembles Napoleon's concentration before Wagram. I am not taking the Prussians too lightly and the minor setback at Regensburg is triggering a concentration of all my available mobile combat forces in the main theater. All told, I will concentrate 8 corps in Germany - 2 at Berlin forming my right flank, 3 in the Ulm area forming my left, 3 in the center at Bohemia. This will face the main Prussian which is operating around the Main River, like so:

Situation in Bohemia by 1 July:

Prussian elements have reached as far as Tabor, cutting the road from Vienna to Prague. Ludwig is badly outnumbered at Munich, facing Blucher at Regensburg, but is hoping to hold out until IV Korps and the Balkan army arrive to relieve him.

However, this concentration will take time. III Korps and VI Korps, for example, are very badly bloodied in Italy attempting to recapture Turin from a French force that came out of hte mountains and captured the city:

III Korps at Turin, VI Korps at Genoa.

The Battle of Turin:

Note the massive number of French infantry elements - 34! to my 25. BUt they have no horse or guns, so I order a massive artillery bombardment rather than an infantry attack into the breach.

This results in lopsided casualties, but the army is exhausted:

By July 1, the city is still holding out, with a tiny garrison, but the battered III Korps must abandon its assaults for the moment and rest and recover.

The news is better in the north. The Army of Silesia shoves over the Oder, capturing Kustrin and Frankfurt, and I Korps pushes hard for Berlin. The small garrison of the unwalled city is captured, something we never managed in any of our Silesian wars:

May 1 - June 26 to reach Berlin, about 8 weeks to capture the city. Napoleon did better in our world's 1806, but this isn't a bad showing by the New Model Army. Situation in Brandenburg:

We hold Frankfurt and Berlin, with small detachments around. A powerful Prussian corps is in Saxony under Hohenlohe, at the fortress of Cottbus.

Situation in the Rhineland:

Mack's Army of France is at Stuttgart and will move on Ulm next. We will rendezvous with III, IV, VI, and VII Corps while bringing up V Corps from Paris when we can, and then this massive force will move out to confront and defeat the main Prussian army around the Main river.

Situation in Europe on 1 July, 2 months into the Fourth Silesian War:

April 5th, 2023, 07:03

(This post was last modified: April 5th, 2023, 10:27 by Chevalier Mal Fet.)

Posts: 3,920

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

The Fourth Silesian War: July, 1810

July 4, 1810. The siege of Turin continues. We have been encamped outside this city for months now, ever since a large army of French stragglers came down out of the Alps and seized the Savoyard capital. I never imagined that it would last this long - this stubborn fortress is now occupying the attention of three Austrian corps, as I have reinforcements on the way to finally close down this objective city. The bombardment is ongoing, and thousands of French are killed or maimed:

But III Korps and VII Korps (my mistake earlier, the formation in Bohemia is VI Korps) are still too weak to storm the city. VII Korps moves away for a couple of months to besiege and re-take Genoa, which surrenders midway through July with 3,000 French prisoners from the garrison. So Joseph gives his men a week of rest, then they slog back across the Po plain towards Turin. Also crossing northern Italy is Ferdinand's Army of the Balkans, landed at Trieste and decided to reinforce this front so I can wrap it up quick. The real action is in Franconia. Situation in Italy changes little by August 1, but I intend to assault Turin before September 1:

In Brandenburg, on the other hand, a Prussian army is moving from Saxony down the Elbe towards Berlin:

I order I Korps to intercept it, with the Army of Silesia in reserve, but the slippery buggers move past me and place Berlin under siege. At the same time, II Korps at Posen winds up faced with a Prussian force of about equal strength. Posen holds out and John's supplies begin to dwindle, so Hildegaard splits his troops - I Korps is moved to defend Berlin, mroe than strong enough to deal with that force, while the main army reserve moves to relieve John:

In Bohemia, IV Korps rapidly crosses the country.

Lichtenstein's army is just over the Elbe from Prague, while the Prussians hold much of western Bohemia. He moves rapidly to relieve Pilsen and Eger, but there are no major Prussian formations - Blucher briefly marches through the territory before moving down towards the Danube at Ulm, so I rapidly clear the invaders from Bohemia:

By the last week of July, I'm at Eger, on the Swabian border, and I have the option to continue IV Korp's march on the Mainz or to move back towards Koniggratz (which fell to Prussian raiders since no garrison spawned, irritating). I decide to continue my concentration on the Main river and pinch out this large Prussian salient, then move into northern Germany in the autumn. The anti-Prussian campaign may drag into 1811.

We'll capture Bayreuth and hten move to link up with Mack. This should bag most of southern Germany and we may trap Blucher or other Prussian corps.

Mack fights the major battle of the war so far - I wish I had time to write detail but I'm pressed for time at the moment. A sizeable battle is fought at Ulm as Mack defeats Blucher's army, which is stronger in artillery and cavalry:

Situation before Ulm. Note IV Korps crossing through Saxony in the north. IV Korps will probably transfer from the Army of Silesia to the Army of the Rhine soon.

Mack and Blucher face off at Ulm, July 22, 1810

Wider look at the upper Rhine region, as the Prussians advance into Alsace:

I have no real forces defending Alsace apart from small garrisons, but V Korps is making its way here from Paris to try and stem the bleeding. Prussians rampage as far as Mulhouse, and Metz falls. But the war won't be decided in this secondary theater - honestly, any gains here are mostly irrelevant. With Berlin in hand, the main goal is to defeat the Prussian field army, then complete the occupation of their territory - Warsaw, Konigsberg, and Magdeburg are the only significant cities remaining.

Battle of Ulm:

Mack's infantry-heavy army (I struggle to recruit sufficient horse, and I don't have the command points to really get the amount of guns I'd like into the army) meets Blucher's artillery-heavy forces outside of Ulm. Mack, once the unhappy general who in our timeline was disgraced at Ulm, covers himself in glory this day. In three days of fighting, Blucher's main army is overthrown, being driven to the north after losing half his numbers on 22 July. The next two days see two cavalry regimetns and an artillery battery captured as reinforcements for the Prussians dribble in far too late to alter matters.

Situation in Franconia and Swabia after the battle

Blucher withdraws northeast, towards Bayreuth. I will maneuver to cut him off with IV Korps and attempt to finish him with Mack. I have VI Korps closing in on Ratisbon/Regensburg below the Danube to seal that, and then I'll be pushing on Mainz in force.

Score and objectives. Turin will fall soon, Breslau needs a stronger garrison:

Posts: 3,920

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

The Fourth Silesian War, Autumn 1810:

Italian Theater

August opens with at last the long-awaited assault on Turin. The French can muster only 6 battalions in defense after the long summer of siege, and there are 36,000 Austrians outside. The result is predictable:

Infuriatingly, a Russian army is in the province at the same time. The Russians mass over 3000 power, which must be at least 60,000 men or more. The Russian general angrily demands that we hand over Torino to his men for safekeeping, as 'good allies.' We have little choice but to accept, since diplomatically the government refuses to declare war on Russia.

As a result, Turin reverts not to Austrian control, but to Russian. What the hell, I'm counting it as occupied anyway, since I'd declare war and take it if I could.

Italy is quiet again, and I leave VII Corps to patrol the Mediterranean coast, chasing French bandits around the lower Alps, while the other two corps move north of the mountains to join the campaign along the Rhine.

Northern Theater - Poland & Brandenburg

The heaviest fighting, though largely static, takes place around Berlin through August and September. First, the Army of Silesia fights an inconclusive, bloody fight at Posen, which chases off the Prussian corps facing II Corps after losing 1/3 of its men:

A follow-up from Bellegarde manages to wipe out the survivors of the Prussian corps, and then Posen itself is stormed with King Frederick narrowly escaping out the back of town as the Austrians swarm over the walls:

The Prussians withdraw east to lick their wounds, and John and Bellegarde are free to move from Poland towards Brandenburg.

There, the elite of I Corps face a succession of Prussian counter-attacks seeking to regain their capital from the occupying whitecoats.

The first battle of Berlin, fought on 8 August 1810 (the same day as another decisive Austrian victory further south) is an absolutely crushing victory, as Marshal Freidrich zu Hohenlohe dashes his 40,000 men to pieces against 75,000 Austrian defenders.

16,000 Prussians are killed or wounded to only 2,000 Austrians, as the poorly-coordinated Prussian assaults are shot to pieces by Hohenzollern each time. Hohenlohe is driven into the wild woods north of the capital, and I Corps is the only formation of strength left in the area:

Hohenzollern pursues the disorganized survivors and manages to scatter the remainder of Hohenlohe's corps. With the victory at Posen that's 2 entire Prussian corps removed from the order of battle:

Not resting, the commander of I Corps then strikes south and manages to surround and wipe out another 10,000 Prussians at Bernau:

The enemy is disorganized and reeling, clearly. Finally, he crosses the Elbe and seizes the great fortress of Magdeburg itself from its 10,000 defenders:

Prussian fortunes all over the northern sector are collapsing, and it remains only to consolidate and then follow up, aiming to rendezvous with the southern armies somewhere in the vicinity of Holland and the North Sea.

Alsatian Theater

The major development in August here is Blucher's attempt to break back to the north. As Lichtenstein's IV Korps cuts the escape paths back to the north, Blucher is forced to abort his thrust to the Danube. The Prussian marshal rallies his army just north of Ulm, then moves over the Thuringer Wald passes - but is intercepted at Bayreuth by IV Korps on 8 August 1810. The resulting Battle of Bayreuth is a massacre:

Blucher's 13,000 survivors from the Battle of Ulm launch three successive attacks on IV Korp's 85,000 entrenched around the Prussian depot at Bayreuth. Each assault, delivered with desperate courage, is turned back by a storm of fire from the New Model Austrian divisions. Half of the Prussian army is disabled in the battle, including all of Blucher's horse - which opens up his army to pursuit from Lichtenstein. The Austrian marshal unleashes his own cavalry in the aftermath, and in the days after the battle Blucher's army disintegrates.

Aftermath of Bayreuth, mid-August 1810

2,600 Prussians are captured either on the battlefield or in the aftermath, and thousands more are killed by the pursuing cavalry. Blucher's army, once the main field corps of the Prussian army, has basically ceased to exist.

The cards fall quickly in Franconia after that. With no field forces remaining in the province, the Prussian garrison of Bayreuth, 5,000 more men, surrenders to IV Korps.

WIth nothing more than a few remnants, to be dealt with by VI Corps, I move IV Corps and the Army of the Rhine to Frankfurt, there to rendezvous and to prepare an invasion down the Rhine, towards Westphalia and the Kingdom of Holland - the last major region in Europe that still holds out against Austria:

IV Corps and the AoR, coming from the east, will join hands with V Corps, III Corps, and the Army of the Balkans, pushing north up the Rhine. V Corps seizes Metz on August 21:

It's a bloody battle, as the 43,000 men of V Corps are met with the 20,000 Prussians of Gneisenau's corps, but the Prussian general comes off (slightly) worse for the wear, and is forced not north, but south, deeper into Alsace. With his retreat past Metz now cut off, I order the AoB and III Corps, coming up the Rhone, to engage and destroy Gneisenau:

Gneisenau is the last Prussian field force in Alsace-Lorraine, and his defeat will clear the way to push as far north as Koblenz and Wesel, the gateway to Westphalia and Holland. I have 5 corps operating here, 1 tidying up Franconia, and the other 4 in Brandenburg-Poland.

Mid-September and IV Corps is leading the attack on Mainz, which has a powerful 20,000 man garrison - no match for IV Corp's 80,000:

While Gneisenau is caught at Nancy and bloodied even further, losing half his remaining men...

And Alsace-Lorraine is free of major Prussian forces by the end of September:

Between this, the Battle of Posen, and the furious fighting around Berlin, Prussia's reserves are pretty much exhausted. The main Prussian field armies have been destroyed, as far as I can tell, as their military has suffered 50% casualties over the past 6 weeks of fighting. Our spies estimate that Prussia fielded 250,000 men in mid-August, but can muster less than 140,000 now - and that's including static garrison troops:

France and the Ottomans are similar, with France having about 130,000 men left in the Grande Armee and the Ottomans numbering about 98,000 men, although they still make a nuisance of themselves in the Balkans - Edirne falls to yet another Turkish army that materializes out of the hills, 25,000 men overwhelming the Austro-Russian garrison.

Overall, as anti-climactic as it is, I think this campaign is drawing to an end. Prussia's ability to resist is clearly declining, and I can't manage the diplomacy to wriggle free of Russia to challenge them for a legal victory. Instead, we'd be stuck in police and patrol actions for the remaining 5 years of the campaign, while I don't think I can win a victory points 'win' due to Russia's enormous lead there. I'll try and polish off Prussia and France, but I think January 1, 1811, will be a good place to wrap this up. We'll do a few Historian's Corners to close out the second half of the French Empire - probably be a few weeks - and then I'll begin the last part of this project: To End All Wars.

Posts: 3,920

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Close of 1810:

As autumn descends on northern Europe, Austrian armies are everywhere unchallenged. The French Empire was largely defeated by the end of 1809, and all Gaul is in three parts: A northern block of fortress cities in the Low Countries has no field forces and has been partially overrun by invading Prussians. Brittany, Normandy, and the regions of France beyond the Loire are largely free of invaders, for now, but are unfortified and have few defenders. Most of Napoleon's marshals are concentrated in Alpine redoubts around Geneva, in Switzerland, where they evade Austrian patrols.

Prussia I think has been largely consumed, its core cities occupied by the sudden invasion of Silesia and Brandenburg, then its armies - at least 5 corps' worth - burned up in the counterattacks towards Berlin and southern Germany in late summer.

So, as Austrians everywhere pray for peace, we begin our final offensive to reduce the last real holdouts, in northern Europe - an arc of cities from Stettin on the Oder to Dunkirk, in France. Capturing these will bring most of urban Europe under our control and we can declare victory.

Here at Koblenz, where the Maas joins the Rhine, is the jumping-off point for our final grand offensive. General Mack has captured pretty much the entire Prussian artillery park and supply train here - look at all those captured units! He spends a few days organizing the vast wagon trains among the streets of Koblenz and in the outlying fields, while the Army of the Rhine prepares for the invasion of hte Low Countries.

Here's the plan:

The main invasion will move down the Rhine, consisting of Mack's army reserve and spearheaded by IV Corps, III Corps in support. On the left flank, Ferdinand's Army of the Balkans will cover the flank, moving to Prussian-occupied Amiens and then beginning to reduce the Channel cities. Linking the two in the center, near the Ardennes forest, is V Corps, which will march on Namur as a hinge between our armies.

That advance goes more or less as planned, unopposed.

Over on the Elbe, II Corps moves down the Elbe towards Hamburg, while the Army of Silesia holds Berlin:

There are skirmishes with the Prussians, but nothing decisive. VII Corps and I Corps are defending my eastern frontiers from raids out of Poland - eventually I will use them to move on Warsaw from my positions at Lodz and Posen, once I clear out Koniggratz (fallen to raiders and NOT SURRENDERING, ugh) and Olmutz (weirdly also fell without a fight - might need to recruit more garrison units and manually occupy these places).

The occupation of the Kingdom of Holland is just that - an occupation. The major battles were all fought over by Berlin, Ulm, and Bayreuth. France's power was long-since spent in its futile second invasion of Austria in late 1807 - early 1808, when msot of them pushed into Vienna and beyond into Moravia, where they were cut off and destroyed.

One amusing note is we find Napoleon skulking with a huge posse of generals and nothing else near the Belgian border:

How the mighty have fallen. The game said he's in exile on Elba, but that was clearly a lie.

And that's largely it. The armies march, the cities are occupied, and there's nothing left to interest me in this campaign.

Final looks at Austria before we jump forward a century, to 1914:

Austria & Hungary:

Pretty much as it started. We have a few provinces here and there with French or Prussian "military control" but every city is ours and garrisoned, and most provinces are even loyal to us.

The Balkans:

Edirne and Nish have been taken by Ottoman guerrillas, but our situation here is analagous to Napoleonic Spain: Austria holds the main cities and roads, while the hilly backwoods belong to large bands of Ottoman mauraders. Constantinople has been Austrian since January 1, 1807, 4 years now. Russia is gradually - oh so slowly - overrunning Anatolia, and has been handling police duties here for ages.

Italy:

Genoa and Turin constantly flip back and forth as French partisans slip around. I've beefed up garrisons here, but this theater has been quiet since our decisive assault in spring 1809. At present Turin is French, but will fall as soon as my generals activate.

France:

Northern and eastern France is occupied, the Channel coast, Normandy, and southern France are still resisting. It woudl be the next major target after the Low Countries.

Prussia:

Major cities are occupied, though we do need an offensive into East Prussia and Poland to truly finish them.

Germany:

Germany is largely neutral, still. Franconia and Bavaria are occupied, as are a few northern cities. Saxony, Hanover, and Kessel remain independent.

The Low Countries:

Our final objectives are overrunning much of these fortified cities, but there's nothing to stop us here.

So our empire stretches from the mouth of the Seine to the Vistula, and from Constantinople to Hamburg. We have the largest army in the world, a small but respectable navy, and solid control over the heart of Europe. Not bad for 6 years of campaigning!

Objectives:

Over a million Austrians died over the course of those 6 years, or approximately half a battalion every single day of the game. That's quite a lot - Austria historically only lost about 350,000 men to military causes over the decade of the Napoleon Wars, with active campaigns in 1805, 1809, and 1813-1814. But I also fought the French, Ottomans, and Prussians, in addition to associated satellites, and I believe many of my losses include prisoners from surrendered garrisons and the like. Uncertain! By way of comparison, here are the losses of the majors, and the counts of prisoners languishing in Austrian camps:

- [li]France: 1,083,539 dead, 274,840 prisoners.

[li]Ottoman Empire: 652,590 dead, 89,000 prisoners.

[li]Prussia: 302,955 dead, 174,600 prisoners.

[li]Bavaria: 15,110 prisoners.

[li]Kingdom of Italy: 28,000 prisoners.

And a few odd thousand Wallachians, Moldovans, 10,000 Swiss, 10,000 Germans, 2,000 British...

On the whole, Austria was a mildly interesting power to play. It's a different experience than France - I've never campaigned in the Balkans before, for example, in my two French campaigns, and the whole area around the Rhine and the Low Countries was new to me since I never had to fight there as France, even if I owned it. But on the whole, Austria is a bit of a disappointment. In the early going, you are so hampered by the inability to form corps and divisions that you can't assemble worthwhile armies, and your diplomacy with France is scripted so you only have the option to fight, and get your ass kicked, or run, and be somewhat bored.

now, the game does unlock a few divisions and corps for you each year, about one of each, so you can gradually scrape together a modern army, but by the time I got my proper army reforms at the midpoint of the campaign, the decisive battles were already over. I think the corps come too late, and history or no AGEOD ought to allow players the chance to form them sooner.

The two really crippling errors for Wars of Napoleon, though, are its diplomacy, and the AI. The diplomacy is clunky, opaque, and limited. Proposals have to be sent, the AI spends a turn stewing over them, and then sends a reply. It's not instant like in Total War. Further, you can't send a proposal to a power when they already have one waiting for you - so the AI would often filibuster me with worthless peace offers and I couldn't make my own! It's opaque - you have no idea why opinions are what they are, there's no real way to alter opinions, and warscore and opinion seem to have nothing to do with willingness to make peace, or sign alliances, or anything. Finally, it's limited. Even with total occupation of every European city in the Ottoman empire, including Constantinople, and including the destruction of their main armies, I STILL couldn't demand all my objective cities, notably Bucharest - so how do I ever make peace and expect to win the game? Not that it matters, as the AI never, ever, ever accepted any peace agreement that included Sarajevo and Belgrade, my other two objectives, despite me having hundreds of warscore and not spending all of it in my peace demands. As a result I was in a forever war with the Ottomans, with the French (couldn't negotiate for Zurich, Turin, Florence, or Milan...), and presumably Prussia (Breslau) and later Russia (Corfu & Kiev). Except I could never attack Russia, since I was in a coalition with them and there was no way for me to exit it!

So diplomacy sucks compared to games like Total War, and forget about Paradox.

Second, the AI in WoN really struggles. Turns chug along, the robot needing 5-10 minutes to calculate moves for the hundred-odd countries on the map, but the AI doesn't perform very well for all that. There are a few times you can see its logic, but it never concentrates armies, it never protects its own lines of communication, hell, it can't even BUILD credible armies - compositions quickly grow weird, like Napoleon's all-engineer army.

So, solitaire, I can't recommend WoN unless you love the period, as I do. I'm told it shines in multiplayer, with real coalition warfare, the chess match of moving and outmaneuvering your opponent, unpredictable invasions and flanking moves, etc. But I don't have any friends, and anyway you need at least 5, maybe even 7, to play a game that processes one turn a week over 11 years - that's 572 multiplayer turns. If you religiously took one turn a day, you'd still need nearly a year and a half to finish ONE game.

I do love the army building and organization, I love having to solve problems of command and supply depots and replacements, in addition to nudging my pixeltruppen around the gorgeously hand-painted map, and nothing matches AGEOD for operational warfare. It's a shame the many flaws bring this game down, in the end.

Posts: 3,920

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Historian's Corner: The Breakdown of the Franco-Russian Entente, 1809 - 1812

In the 2 1/2 years following the titanic battle of Wagram and the collapse of the Fifth Coalition, Europe enjoyed something very nearly approaching peace. To be sure, at the fringes there was still war - Russia fought Sweden in Finland and the Ottomans in Bessarabia, Britain continued to nip away at French coasts, and the Spanish ulcer dragged on - but for a few years the god of war, Napoleon, was quiescent in Paris and the massed legions of Europe rested.

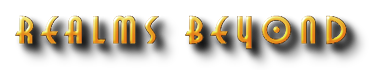

Most of the fighting for these years was in Spain. In 1809, after the British army narrowly escaped the Peninsula at Corunna, Marshal Soult had gone on to re-invade Portugal. As the furious Danube fighting between Austria and France erupted in April, however, Britain took the opportunity to return to the Continent. A small army was landed under Arthur Wellesley in Portugal, again, and a larger expedition was dispatched to Walcheren island at the head of the Scheldt, to raid French shipping and distract Napoleon from Austria. The Walcheren expedition turned into a costly debacle and was over by December, but Wellesley soon drove Soult's corps out of Portugal, and that summer in partnership with his Spanish allies, he marched on Madrid itself - winning his first major battle against a proper French army at Talavera in July, 1809. However, the ramshackle Spanish government was unable to support the British expeditionary force with promised money or supplies, and the army was unreliable, so Wellington withdrew to the Portuguese frontier.

In 1810, with no distractions, French reinforcements poured once more into the Peninsula. Soult led the invasion of Andalucia, carrying the French flag as far as Cadiz, which narrowly held out under siege, with heavy Royal Navy support. That summer, Marshal Massena, fresh from the Danube campaign, stormed into Portugal for the third time. Wellington bloodied their nose at the Battle of Busaco, but in the face of overwhelming numbers he fell back to Lisbon behind the Lines of Torres Vedras, a massive system of fortifications across the Lisbon peninsula that would require a regular siege to storm. Wellington had also scorched the earth in front of the Lines, so that the country could not support Massena's massive army. With his supply lines winding all the way back to France across Portugal and Spain, Massena could not remain and quit Portugal for the last time late the next spring.

The French war effort in Spain broke down into a series of petty fiefdoms as the various marshals feuded with each other and fought separate wars. The geography of the peninsula almost demands this. There is a single high central road from France through Basque Country down to Madrid, via Vitoria and Burgos. The central plateau around Madrid is high and barren, and a barrier of mountains separates the coastlands from the center of the country. Further mountain ranges subdivide the various coastal provinces from each other, so that Galicia communicates little with Asturias, neither with Cantabria. Catalonia and Valencia are virtually separate kingdoms over in the east, Mercia in the southeast is isolated, etc. In the south, as mentioned, was Soult, campaigning in Andalucia, especially against Cadiz. Marshal Suchet led the war in Valencia. Massena fought in Portugal. So the French moved up and down the high road in the central plateau, while the Royal Navy periodically raided the coastlands or dropped off weapons and supplies with the Spanish partisans. And of course, the various mountains were rife with guerrillas, cutting off French convoys and messengers and picking off isolated garrisons constantly. The Empire bled men steadily all over the peninsula.

Through 1811 the war was stalemated. The British and Portuguese could maintain only a small army in Portugal, the Spanish regular armies skulked in isolated sanctuaries like Galicia, while the long supply lines and huge garrison requirements of the French similarly limited the numbers they could deploy at the far ends of the peninsula. So 1811 was dominated by sieges of border fortresses like Almeida, Badajoz, and Ciudad Rodrigo, as the armies marched and counter-marched to variously besiege or relieve the various forts. There were two sharp battles, at Albuera and at Fuentes de Onoro, but by and large the front lines shifted little. It wasn't until 1812, when Napoleon was forced to withdraw large amounts of men for his impending Russian campaign, that the balance shifted.

So, let's turn to the famous Russian invasion of 1812, and trace the path there.

The road to Moscow was years in the making, beginning practically before the Tsar and the Emperor parted ways at Tilsit. Fundamentally, however much Napoleon and Alexander sincerely desired friendship, the interests of the two empires were irreconcilable: Napoleon was determined to support the Poles in the Duchy of Warsaw, while Alexander wanted his Polish subjects cowed and quiet, Alexander wanted to extend Russia's influence beyond the Bosporus to the Mediterranean, which Napoleon equally opposed, and on top of it all the Continental System was a massive burden on the Russian economy. The Russian nobility and peasantry were united in their hatred of France and their desire to shake free of the onerous yoke of Napoleon. From 1809, after Russia failed to support Napoleon against Austria (and the Emperor retaliated by awarding the Duchy of Warsaw Austria's Galician possessions), the downward slide was on.

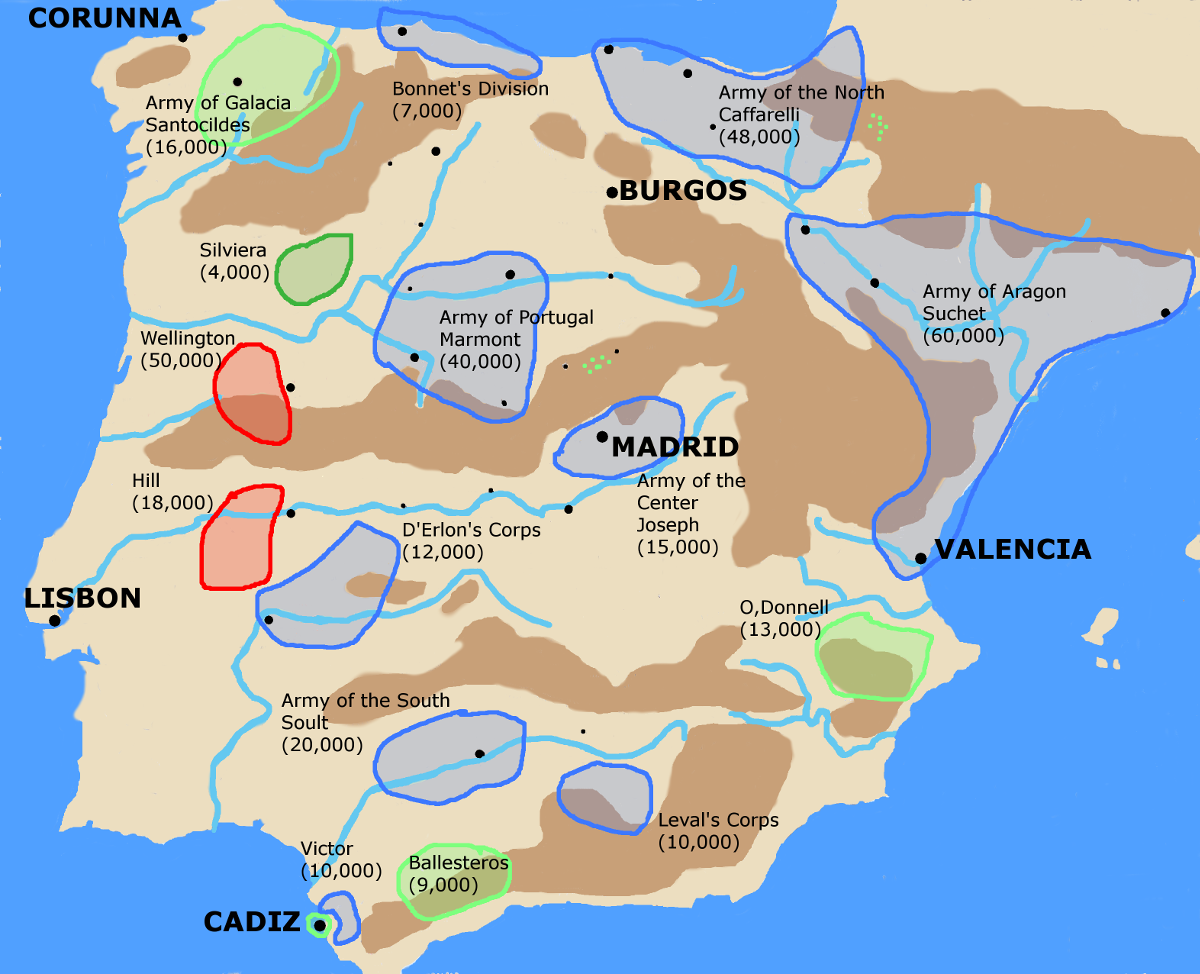

In 1810, Napoleon, keen to produce an heir to his empire, divorced the barren Josephine, and after negotiations to marry a Russian princess stalled, abruptly announced his engagement with Marie Louise Habsburg, the daughter of the Austrian emperor! From there things began to spiral. Friction over Poland, over the Balkans, grew. French agents tried to stir up Turkey and Persia against the Tsar, Napoleon seized lands along the North Sea that were flaunting the Continental restrictions - lands that belonged to the Tsar's brother in law. In 1811, the Swedish crown (as discussed in more detail previously) was suddenly offered to Marshal Bernadotte, the Prince of Ponte Corvo. Russia saw these moves - alliance with Austria, intrigues in the Middle East, now a Napoleonic puppet in the Baltic - as part of a concerted conspiracy to surround the empire with enemies.

Napoleon's imperial connections, 1810

From Napoleon's perspective matters were equally worrying. In the first place, of course, Bernadotte was no French puppet - Napoleon could barely stand his former marshal. Russia was clearly flouting the Continental System frequently, sustaining Britain's forever-war with him. Alexander even began to place tariffs on French goods while allowing 'neutral' ships into his harbors! Napoleon became convinced by August 1811 that war was inevitable to bring Russia back to heel, and began his preparations accordingly. "Bah! A battle will dispose of the fine resolutions of your friend Alexander and his fortifications of sand. He is false and feeble," he sneered.

Alexander wanted to avoid war, for his part, but he would be ready for it if it came. He said to the ambassador, Caulaincourt in 1811 a perfect prophecy of the war to come:

Quote:If the Emperor Napoleon decides to make war, it is possible, even probable, that we shall be defeated, assuming that we fight. But that will not mean that he can dictate a peace. The Spaniards have frequently been defeated; and they are not beaten, nor have they surrendered. Moreover, they are not so far away from Paris as we are, and have neither our climate nor our resources to help them. We shall take no risks. We have plenty of space, and our standing army is well-organized. Your Frenchman is brave, but long sufferings and a hard climate will wear down his resistance. Our climate, our winter, will fight on our side.

The die was cast, though - Napoleon would make war rather than let Russia exit the Continental System, and Russia would accept war rather than meekly surrender. Napoleon began to gather his German allies in January of 1812, mobilizing Bavaria, Westphalia, and the Confederation of the Rhine. Demands were also sent to Austria and Prussia for 60,000 troops. Russia countered - Swedish neutrality was bought by offering her Norway (Bernadotte cheerfully accepted after Napoleon casually annexed Swedish Pomerania in March 1812, to secure his flanks before a march into Russia), peace was signed with the Ottomans, and an alliance was signed with Great Britain in July (after the invasion began), flooding Russia with money and especially direly-needed weapons. The army was reformed and reorganized on French lines. When the war came in June of 1812, Russia was the most formidable opponent Napoleon had yet faced.

April 6th, 2023, 11:14

(This post was last modified: April 6th, 2023, 11:16 by Chevalier Mal Fet.)

Posts: 3,920

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Historian's Corner: The Road to Moscow (January - June, 1812)

Russia's preparations for war had begun in 1810, when Barclay de Tolly began the extensive army reforms that would bring the Tsar's army into the 19th century. The Russians changed their organization, their administration, their system of recruitment. They deployed new muskets, new cannon, new boots and new uniforms. They reorganized and improved their artillery, already among the best in Europe. By June 1812 Alexander could call on over 200,000 well-trained first rate soldiers, another 45,000 forming, and over 150,000 in reserve and garrison formations. However, the staff was still inefficient, transport and logistics terrible, medicine almost non-existent. The officer corps was in general slothful and incompetent, albeit brave enough. Corps generals and up were of better quality - Barclay de Tolly commanded First Army, arrayed to defend the Dvina River and the Baltic states. Commanding Second Army, in Belorussia, was Prince Peter Ivanovich Bagration, a solid fighter but reckless, like Ney or Murat. Third Army, south of the Pripyat Marshes in Ukraine, was commanded by Count Alexander Petrovich Tormasov. Looming over these three army commanders was Mikhail Kutusov, a legendary soldier iwth over 50 year's of experience. Though technically in command at Austerlitz, no one particularly blamed him for that disaster. Kutusov was officially in retirement, but that was unlikely to last long when war broke out. Then there came Bennigsen, responsible for Eylau and Friedland, currently in disgrace. The Cossacks, 15,000 of the finest light irregular cavalry in Europe, were led by the able Platov. These men would face Napoleon and his marshals, whom we have already met during their various adventures across Europe.

Napoleon prepared exhaustively, reading every book he could about Eastern Europe, including many campaign histories of Charles XII of Sweden's disastrous 1709 invasion. He concluded he would need an army of fully 600,000 men for the task (and in the process, created a new formation - the army group). Napoleon assembled over 200,000 veterans on the Polish border, to be beefed up by 50,000 Italians, 130,000 Germans, 50,000 more Poles, and the aforementioned 60,000 Prussians and Austrians. This mass of manpower was the most difficult organization task the Emperor ever undertook. 450,000 were formed into the three main armies of invasion. Napoleon himself would lead two cavalry corps (under Murat), the Guard (over 50,000 strong now), and three corps under Davout, Oudinot, and Ney. Davout's I Corps was over 70,000 strong, while II Corps under Oudinot was 37,000. This was the most French-heavy of the three armies and totaled 250,000 men. In support were two more armies - his stepson Eugene of Italy led 80,000 Italians and Bavarians, while his brother Jerome of Westphalia commanded 70,000 Poles and Germans. Finally, on the extreme flanks were two final corps - X Corps (32,000) under Marshal Macdonald (promoted after Wagram) on the Baltic, and the Austrian Corps (34,000) under Schwarzenberg on the right. In reserve were further corps: IX Corps, Victor, 33,000 men, XI Corps, a French and Polish formation, Lithuanians, and more German levies, about 165,000 men. Finally, Augereau led an ultimate reserve of 60,000 men in garrisons along the Vistula.

Napoleon's mound at the Niemen, where he began his invasion.

All told, it was the largest army Europe had ever seen, but the quality was necessarily diluted. Less than half of it was French, for example - there were over a dozen nations represented. The loyalty of many of these troops was suspect, and their motivation and morale low. Napoleon had no idea how to command such an immense host - he concentrated most power in his own able hands, but his subordinates had too little experience of independent command and often fumbled when out of their master's eye. The officer corps was of much lower quality than in 1805 - 1809, necessarily, most of the men were green conscripts, and the cavalry mounts totally unsuited for Russia's harsh climate (this last point is perhaps the most significant!!). Now, Napoleon DID go to herculanean lengths to create a massive supply and support system for this vast host. He knew the Russians would scorch the earth, he determined to carry everything with him. He assembled over 250,000 animals hauling 25,000 vehicles - supply wagons, hospital carts, ammunition caissons. Barges and boats were assembled to make as much use as possible of the rivers in western Russia. One oversight was the lack of winter clothing, but in retrospect the great damage to the Grande Armee was done before General Winter ever took the field. The task was simply too immense for 19th-century logistics to handle.

Most of the campaign would be fought north of the Pripyat. South of that massive swamp is the Ukraine, broad plains bordering Austria's Carpathian mountains. The Russians had Tormasov's Third Army guarding this area, observed by Schwarzenburg's Austrian Corps. But Napoleon's emphasis was on bringing the Russians to battle as speedily as possible, and he concentrated on the more populated northern half - the Baltics and Belorussia. This terrain is broken by a series of rivers, in order: the Vistula, the Niemen (the frontier), the Vilia, the Berezina, the Dvina, the Dnieper, and finally the Moskva. The land was largely swampy and forested, sparsely inhabited until you pass Smolensk, where rolling farmland up to Moscow is the norm, though still largely empty by European standards. Napoleon chose this area because it was closer to the Duchy of Warsaw, it was mostly populated with 'friendly' Poles, and it was closer to both Moscow and Alexander's capital of St. Petersburg.

As for his actual war plan, it was simple and well-chosen. Napoleon would penetrate between Barclay's First Army and Bagration's Second Army, then fall upon Barclay and destroy him before turning on Second Army. If the Russians fell back to the east, Napoleon would pursue, continuing his efforts to divide and destroy them. If they massed in the south, he would sweep past their right flank on the north, pin them against Pripyat, and destroy them that way. Or, if Barclay delayed him while Bagration tried an attack on his rear, he would be able to defeat both armies in detail. The key would be rapid movement to catch the Russians napping and fight the decisive battle near the frontier. Unfortunately for Napoleon, he had at last reached a stage too big for his talents. His personal genius and energy worked well enough with armies of 200,000 in northern Italy, the Danube basin, or northern Germany - but now he was trying to personally supervise nearly 700,000 men in a theater a thousand miles across. His subordinates had no concept of acting on their own and inevitably fumbled when Napoleon was elsewhere. Secondly, he demanded too much of his raw conscripts - too rapid marches pushed too far.

For their part, the Tsar and his advisers were crafting a plan to foil the invasion they all saw coming. Modern scholarship shows that the Russian plan of delaying battle and drawing Napoleon deep into the heart of Russia, where time, distance, and the climate would sap his strength before the decisive battle, was quite deliberate. The Russians fortified a massive camp at Drissa, on the Dvina River, where they initially planned to make a stand. In the event, the campaign opened with the Russian armies too widely separated for this initial plan to be viable, but the basic framework remained in place all the way through the battle of Borodino.

By mid-May, the Grande Armee was concentrated on the Vistula between Danzig and Warsaw, and began moving to the Nieman. Already the supply system was breaking down and the frontier hadn't even been crossed yet - troops struggled to find food and to keep the punishing pace that was set. By May 30th, the army was in place. The French waited, poised on the brink for three weeks while waiting for the grass across the river to ripen. The deep breath before the plunge - and then, on June 22nd, 600,000 soldiers of the Grande Armee crossed the Niemen into Russia. Few would ever see their homes again.

Posts: 3,920

Threads: 18

Joined: Aug 2017

Historian's Corner: "What are you doing here? F*** off!" - July, 1812

On June 22, 1812, the leading cavalry patrols of the largest army ever assembled cautiously trotted to the far bank of the Nieman. Late the next day, the lead elements of the Grande Armee began to file over the pontoon bridges and onto the soil of Holy Russia for the first time. But the front was quiet. Instead of meeting Barclay's advanced posts, there was nothing but a few cavalry patrols on the border. Officer of Polish artillery Roman Soltyk wrote: "… a strong troop of Muscovite hussars halted at about a 100 paces from our weak advance guard. … Coming toward us, the officer shut out in French: Qui vive ? "France!" - our men reply quietly. "What are you doing here ? F… off !" - shouted the officer of Lifeguard Hussars." The lack of opposition was a troubling sign - Napoleon intended on a rapid, decisive battle near the frontier to destroy Russia's army and bring Tsar Alexander to terms, not a march deep into the heart of the largest state in Europe. But de Tolly's First Army was already beating feet, making all haste for the strong Dvina line and their fortified camp at Drissa (in accordance with their pre-war planning, obviously all unknown to the Emperor). Napoleon quickly adopted plan B, ordering a rapid push towards Vilnius while Jerome's Army of Westphalia was to attack Bagration's Second Army and pin the Russians down for the Grande Armee's decisive envelopment from the north. All depended upon speed and aggression.

The key to understanding the summer campaign of 1812 is that it's a footrace. To the north and south you have Barclay's First Army and Bagration's Second Army. Barclay and Bagration want to join up so they can fight the French as one big body. But the French invasion caught them badly deployed (due to internal Russian debates over the best way to meet the invasion), and now Napoleon is in between them. To join up they have to get around him to the east, but he's ALSO marching east as quickly as he can to keep between them. If the Russians slip in the race, then Napoleon gets to fight half the army with all of his. If the French slip, then the Russians can get ahead of them and finally turn the corner to join up. So, you gotta understand all the movements through June, July, and August in that light - the Russians want to link up, the French want to keep between them, and the result is one of the most desperately marched campaigns in history.

The schedule was already slipping. Eugene's Army of Italy, the link between Jerome and his brother Napoleon, was 2 days behind schedule due to the enormous transport convoys Napoleon had organized, and the Grande Armee could not push to Vilnius and beyond without Eugene up to safeguard the line of communications. Jerome, for his part, was sluggish and timid, not wanting to come to grips too quickly with Bagration. Murat, back in command of the cavalry for the first time since 1807, was racing hell for leather for Vilnius but the Emperor felt compelled to rein him in a bit. It was not until June 28 that the Lithuanian city was reached - and the Russians were already firing it and pulling out on the far side. The French had already outraced their supply convoys and the men were growing hungry, straggling and desertion were increasing - but the Russians had not yet fought a battle, and their army was still unbeaten in the field. Napoleon pressed on.

Murat was dispatched to pursue Barclay's First Army, which was scampering northeast beyond Vilnius towards the Dvina river, with Oudinot and Ney's II and III Corps in support. Davout's I Corps, as large as the other two combined, was to push southeast hell for leather to cut Bagration's line of retreat and prevent the union of the two Russian armies, towards Minsk. Rain poured down in the last week of June. The supply convoys fell behind in sucking mud. Cossacks haunted the Grande Armee's patrols, keeping their cavalry from scouting and their men from foraging. The three armies, wet, hungry, tired, slogged on.

Cossacks vs Polish lancers, 1812

By 1 July, Napoleon thought he had Bagration trapped, as Second Army approached Vilnius from the southwest. But Eugene was slow bringing up the Army of Italy still (slowed by the appearance of a phantom Russian army on his left flank, a figment of his imagination), and so Davout was slow jumping off to the southwest to block Bagration. Jerome still had hardly budged on 3 July, and only got around to notifying Napoleon that the Russians seemed to have vanished from in front of him on 5 July. Napoleon was furious with his brother.

Quote:Tell him [he wrote to Berthier] that it would be impossible to maneuver in worse fashion...that I am severely displeased that he failed to place all the light troops at Poniatowski's disposal for the purpose of harassing Bagration; tell him that he has robbed me of the fruit of my maneuvers and of the best opportunity ever presented in war - all on account of his singular failure to appreciate the first notions about warfare.

Jerome was so offended by Napoleon's scathing critique that he quit the campaign in high dudgeon, which was probably a net gain for France, honestly.

July 1, 1812 - visible are Murat, Ney, and Oudinot pursuing Barclay's First Army to the north, while Jerome totally fails to pursue Bagration's Second Army and Davout hustles to cut him off at Minsk.

Davout hurried his men on to Minsk, still hoping to cut off Bagration, arriving there on 8 July - but found that Bagration had altered course to the south, high-tailing it to Bobruisk as soon as he got wind of Davout's approach. Untroubled by Jerome's tardy columns, Bagration was able to afford Second Army three days' rest, after 9 days of non-stop marching. The French army's poor perfomance - Jerome's failure, the lumbering supply convoys, the ever-present Cossacks - had led Napoleon's first effort to end on complete failure.

So, Napoleon swapped his efforts to the north, and Barclay's First Army. That force was by now arriving at its positions behind the Dvina, near the great camp at Drissa the Russians had built as the linchpin of their defensive strategy. Napoleon now planned to pin First Army in place with Murat, while he swung the rest of the army over the Dvina upstream of the great fortress at Vitebsk, forcing Barclay either to fight or to flee for St. Petersburg. Through the second and third weeks of July the men of the Grande Armee slogged their way eastwards, through heat and through dust. It was a killing pace. Men dropped out with sunstroke, dehydration, and exhaustion. Men who straggled from weariness, illness, or hunger were set upon by the Cossacks or the peasants and murdered. And for all that, Napoleon drilled another dry hole.

Barclay was straining every nerve to join up with Bagration before the great battle, and he abandoned the camp at Drissa, into which so much wealth and effort had been poured, without firing a shot. His men hustled up the Dvina on the far side from Napoleon's columns, towards Vitebsk. To the south, Davout raced to keep ahead of Bagration, swarming over the Berezina upstream even as Second Army crossed that river at Bobruisk. The two armies sped over the Russian plain on parallel courses, the Russians finding any attempt to turn north resolutely blocked by Davout's hard-marching veterans. A sharp fight at Mogilev on the upper Dnieper on 23 July saw Bagration decisively blocked and turned back south, even as Barclay reached Vitebsk, the point where the Dvina most closely approaches the Dnieper.

At that place, the gap between the two rivers narrows to only 45 miles or so. This strip of land is the traditional invasion route between Moscow and the rich lands to the west. At the center of it sits the ancient and holy city of Smolensk - and so it is that Smolensk is the gate to Moscow, the point at which all roads to the spiritual capital of Russia converge. By July 25, Napoleon had reached the vital land bridge, opposite Barclay in Vitebsk, while Bagration was moving south down the Dnieper seeking an alternate crossing point. Believing he had succeeded and that Barclay would fight, the Emperor made his most catastrophic blunder of his career: he decided to wait a day for his armies to fully concentrate.

The Russian dust and mud, the heat, the rain, the Cossack and peasant war, the unwieldy supply convoys - everything had conspired against the Grande Armee to this point. Napoleon's corps had none of their vaunted speed, and not everyone was up. Napoleon knew what stubborn fighters the Russians were, perhaps had memories of Eylau and Heilsburg's charnel houses in his mind, and so he paused for one fatal day. During that day, Barclay, who had indeed planned on battle at Vitebsk, heard that Bagration had been blocked, again, and decided to attempt one last rendezvous at Smolensk instead of Vitebsk. During the night, First Army slipped away, and when the French advanced in full battle array on the 28th, they saw that the birds had flown.

There were many good roads linking Vitebsk to Smolensk, and many from that place to fords along the Dnieper - no doubt Bagration was already across and speeding towards the city. With his strategy in ashes, Napoleon reluctantly ordered a halt to rest and refit at the end of July, 1812. In five weeks, he had pursued the Russians over 600 kilometers from the frontier, inflicting only 8,000 casualties in the breakneck campaign, and wrecked his army in the process. The Grande Armee had lost tens of thousands of men and (significantly!) horses to sickness, exhaustion, and desertion in the five weeks. Over 100,000 men, nearly 20% of the army, were lost to sickness or straggling, ruined by the too-rapid marches. So, for 8 days, the Grande Armee rested, reorganized, and brought up its late convoys.

On the flanks, during July, there was more fighting than in the central area's Great Race. To the south, the Russian Third Army made its way north from Bessarabia and was sniffing around the fringes of the Pripyat barrier, blocked by Reynier's VII Corps and Schwarzenberg's Austrian corps. To the north, Macdonald's X Corps moved north to besiege Riga on the Dvina, keystone of the left flank, and Oudinot's II Corps dueled a Russian corps under Wittgenstein at Polotsk, on the middle Dvina, through July and August.

Situation, 1 August 1812

So far, a month into the invasion of Russia, Napoleon's decisive battle on the frontiers had eluded him. Instead, the Russians had lured him deep into the heart of the empire, and had successfully concentrated their armies despite the emperor's best efforts. The French front had extended from 250 miles (Konigsberg to Lublin) in June to now over 500 miles, a massive arrowhead stretching from Riga to Vitebsk to Bobruisk and then along the Pripyat back to Lublin. Detaching men to hold this long front, wastage from disease and desertion, had reduced Napoleon's main striking force down to only 156,000 in the central army group by this point. The men were worn out by the Cossack's hit and run raids, growing increasingly paranoid and jittery. The Russian strategy was working.

|